Photography in Aotearoa is notable for the contribution of female artists. Ans Westra, Marti Friedlander, Fiona Pardington, Yvonne Todd, Marie Shannon and Anne Noble are practitioners who have been recognised by major awards, monographs and career survey shows. Photographs by these artists have been acquired by public galleries and actively pursued by collectors from their representative dealer galleries and at auction. Collectively these artists represent a cohort whose practice emerged and then flowered from the 1960s to the present day. Equity of opportunity, market acceptance and wider cultural impact seems to have been so well and truly achieved that it does not seem relevant or noteworthy to mention that the top ten prices achieved at auction for the photographic medium is dominated by just one artist, Fiona Pardington.

But that is now. What about then? That is the central premise of Through Shaded Glass, which picks up the thread from the earliest known photographic images produced by women in the 1860s and from there, charts a course to the late 1950s, when Marti Friedlander and Ans Westra’s careers began. Author Lissa Mitchell – Curator of Historical Photography at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa – has assembled a thorough body of research and conducted an equally impressive campaign of image sleuthing. What previously seemed the cultural equivalent of one hundred years of solitude is now revealed as the visual equivalent of a Broadway musical, complete with an ensemble cast. From taking, developing and retouching to marketing photographs, the women of Through Shaded Glass were making magic happen every day.

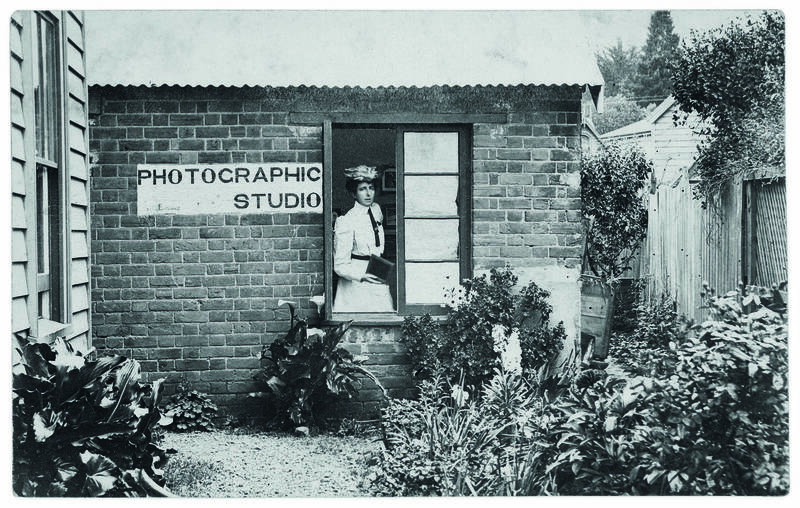

Jessie Buckland in the window of her photography studio, Akaroa, about 1910. Unknown Photographer. Copy negative. Hocken Collections Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago. c/nB613.

At rough count, Mitchell has either unearthed or enriched the account of 190 image-makers and photographic entrepreneurs from a longlist of 450. Outside the images themselves, perhaps the most notable revelation of Through Shaded Glass is the bustling energy of commercial endeavours managed by women as principals of photographic studios from the 1860s. In the nineteenth century, running a photographic studio in Aotearoa was a family affair. It was all hands on deck – wives, husbands, sisters and daughters. The stock-in-trade of photography then was documenting a burgeoning colony, selling the idea of New Zealand as a Little England in the South Seas to anxious relatives and prospective future immigrants.

In the last decades of the nineteenth century, three categories of imagery dominated. Portraiture – particularly families and children galore, but also soldiers, politicians, clergy and graduation milestones – continued to be the bread-and-butter work for photographic studios right up till the 1960s. The burgeoning postcard trade demanded field work. Large-plate cameras hauled into the interior captured New Zealand as a ‘Land of Loveliness’ for future tourists and settlers alike. In the first decade of the twentieth century the volume of postcards sent in and from Aotearoa exploded from 1.4 million in 1903 to 11.5 million in 1912.

Historically, perhaps the most important category of photography prior to 1900 was images of Māori, either studio portraits of leading figures of the day – such as the second Māori king Tāwhiao (Ngāti Mahuta, Tainui) – or in situ field images of the great whare whakairo and wharenui, such as Tamatekapua, Hinemihi o Te Ao Tawhito, Mataatua and Te Tokanganui a Noho, that emerged from the 1870s. Such images became ubiquitous, distributed via the trading card like cartes de visite or dedicated photography albums, highly collectable today.

One the most significant figures of this period was Elizabeth Pulman (1836–1900). Widowed ten years after arriving in New Zealand in 1861, she inherited her husband’s photography and, while raising nine children, successfully ran Pulman’s Photographic Studio in Auckland. Her output included all three of the imagery categories above and through Mitchell’s research she is revealed as among the leading rank of New Zealand photographers, alongside more comprehensively documented figures such as the Burton Brothers, George Valentine and the Rev. John Kinder.

The book’s ‘deliberate focus is on individuals,’ MItchell writes in the introduction, ‘not to argue for them as exceptional but rather to combat anonymity and generalisations, particularly in the case of working-class women’. In Through Shaded Glass a number of photographers emerge as significant, even canonical figures. Una Garlick (1883–1951), Thelma Kent (1899–1946) and Ramai Hayward (Ngāti Kahungunu, Ngāi Tahu, 1916–2014) are just three practitioners whose biographies and mahi toi are ready for more expansive treatment. So does the kaupapa of Māori photographers – including Mākareti Papakura (Tūhourangi, 1873–1930), better known as Guide Maggie – whose mahi warrants further investigation.

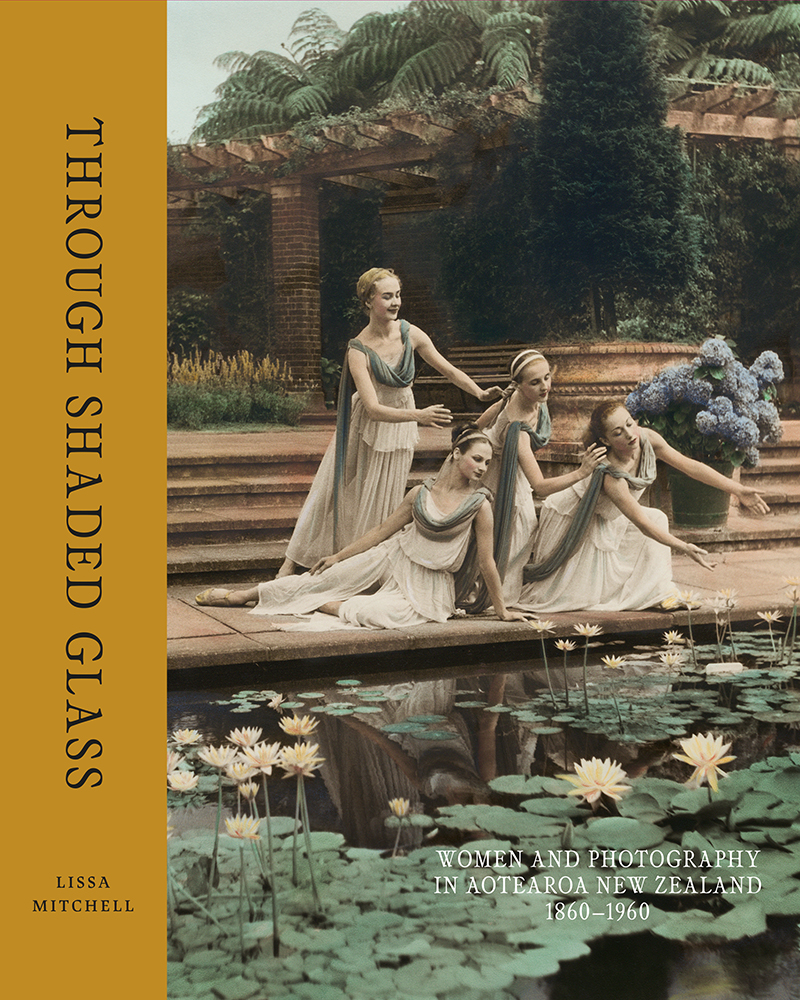

A hundred-year span is explored via six thematic chapters, interrogating both the images and the intent of the photographers. The more quotidian business of photography – weddings and studio portraits – is fundamentally documentary in nature, with the odd tinge of hand-coloured romanticism. Through Shaded Glass also documents nascent art photography, staged photographs that are pictorially or thematically driven. The book’s cover, a mis-en-scène image by Lily Byttiner, is perhaps the supreme example of this genre. It’s a hand-coloured photograph from 1950 of four graceful sirens arranged around a lily pond in Auckland’s Wintergardens, an image that echoes the allegorical elegance we see in the canvases of the painter Lois White from the same period.

The chapter ‘Being Modern’ charts the beginnings of a distinct artistic sensibility emerging in the images from a cohort of photographers – Irene Koppel, Eileen Deste, Byttiner and Maja Blumenfeld – who clearly wanted to extend the communicative possibilities of the medium beyond competent studio portraits. Expressive, even cinematic, these images from the 1930s and 40s give agency to both subjects and photographers and speak of an ambitious band of women committed to a creative, independent lifestyle.

Vital to these ambitions were the many photographic competitions, organised by provincial camera clubs and a common adjunct to agricultural field days, Expos and Easter Shows in the interwar years. In this context women exhibited on an equal footing with men. Cups, prizes and honourable mentions, and advancement to national competitions, gave photographers the oxygen of publicity and important critical feedback – technical and sometimes aesthetic. These limited opportunities enabled image makers to engage with the public, and established as both creative and professional exponents of the form well before photography entered the gallery space in the 1970s.

This level of granular and contextual research is one of the real strengths of Through Shaded Glass. Mitchell has resisted the temptation to create a pantheon or ‘top ten’ group of primary talents: many photographers’ work is known only through a handful of images or secreted within family archives. No doubt this richness of archival material will have readers rushing to their own family albums to seek out photographs not dissimilar to those on the pages of Through Shaded Glass.

She also reveals the restlessness of the medium as well as post-capture manipulation of images from the outset. Contemporary disruptors of ‘truth’ in a photographic image include Photoshop and AI, but previous generations of photographers deployed and debated all manner of darkroom tricks, including hand-colouring and the finessing of images through lighting. Mitchell notes that in many cases the clients for family portraits, the photographers themselves, studio technicians and specialists in re-touching were all women.

Hand-coloured view of the New Zealand Centennial Exhibition tower, 1939–40. Eileen Deste Studio, Wellington. Gelatin silver print. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. O.020401.

The range of technically challenging processes and machinery associated with photography over the century in question is, for the specialist reader, a gearhead’s playground. Deserving of special mention in Through Shaded Glass is its glossary of photographic terms. Though readers drawn to the book’s images may not care about differences between an albumen silver print, a gelatin silver print, a platinum print and a bromoil, the glossary emphasises the constant change across all aspects of photographic production after 1860.

From the relatively mundane to the magnificent, Mitchell’s decade of research has unearthed a wealth of wonderful images created by women in Aotearoa, and provided a powerful narrative that reveals their creators’ lives and motivations. Through Shaded Glass is both a corrective and a celebration, and will no doubt create a legacy in its own right, as a point of departure for future scholarship.

Amy Harper and Dickie Steer with camera on tripod and Flashbulb, 1979. Paul Anderson, Auckland.Gelatin silver print. Auckland War Memorial Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hera, Auckland Star Collection. PH-1980-8-1.