In the last year we have seen writers scorned and pilloried for daring to write about what they are not. Jeanine Cummins was forced to apologise for having a Mexican woman refugee as her central character in the bestseller American Dirt. Jeanine Cummins is neither Mexican nor a refugee. Kate Elizabeth Russell, another American writer, was forced to disclose her own childhood abuse after publishing her controversial and brilliant novel My Dark Vanessa. Current mores seem to dictate that writers may no longer strive to achieve the age-old alchemy that was once the province of writers, that is, to enter fully into the hearts and minds of characters different from themselves, and to speak for them.

There is one subgenre that seems to be safe from this lunacy — the historical novel. There, perhaps, we are still allowed to indulge our imaginations. Ian Wedde was not born a woman in Kiel, in the north of Germany, in the nineteenth century. As far as I know he has never fallen pregnant from a rape. I doubt he’s handy with the embroidery needle, but maybe he is, just like Josephina, his compelling central character in the exquisitely researched The Reed Warbler.

The novel does not begin with Josephina, but with her descendants Frank and Beth. The elderly second cousins make a long-delayed journey to the Kaitieke valley where a closer ancestor, also descended from Josephina, had a farm and raised his children. Exposition intrudes a little into their dialogue, with an unnatural ‘My grandmother née Hansen’, but this is an understandable flaw in the Herculean effort to explain a complicated family structure going back six generations. Mercifully, at the front of the book, there is a family tree.

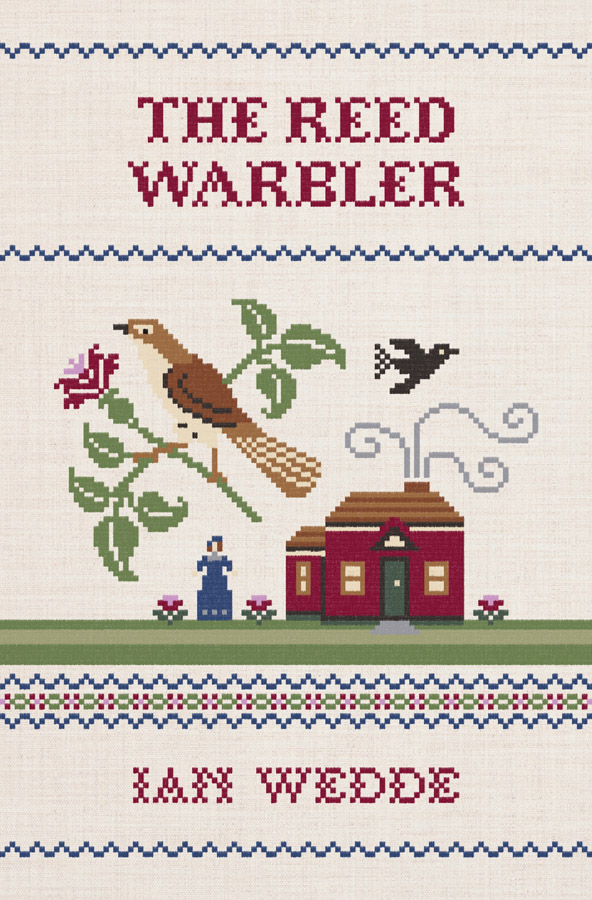

Frank and Beth are fresh from a family reunion, where various family taonga were on display, including ‘that sewing-sampler thingie … Nobody really knew about these things, and they could mostly only go ooh-ahh because they were so old, imagine that, what was life like back then?’

The sampler is what Josephina, throughout her life, called the Oma, because her grandmother had given it to her. ‘The Oma was half the size of a bed and couldn’t ever be washed because the different threads and dyes would get mixed up … Her grandmother would close her eyes and breathe in deeply whenever she unrolled the sampler, and would always tell the story or sing the song of the stitch she was using that day.’ Josephine was her devoted granddaughter and pupil and so, over a century ago, the Oma made the voyage to New Zealand and is cherished in turn by her descendants.

Frank is a good bloke. He likes a drink and has long conversations with his beloved dead wife when he’s alone in his room at night. Ten years older than Beth and long domiciled in Australia, he is a repository of both the New Zealand and Australian vernacular and ‘bad Aussie jokes’. In the first chapter, a little wearied by the mania for genealogy that has gripped his relatives, he remarks ‘What happened to good old you’re born, they rip out your tonsils, most of your teeth, your spleen, your man’s foo-foo valve, and then you die?’

That succinct approach certainly wouldn’t have sufficed for Wedde, who acknowledges that The Reed Warbler is fictionalised family history. In three parts and various close third-person narratives, the story moves from contemporary New Zealand to nineteenth century Germany and back again.

We first meet Josephina as a young woman, living with her family in Kiel. Already a gifted seamstress and embroiderer, she delivers a nightgown to the absent wife of a repellent Pole, Hauptmann von Zarovich, who has snot in his moustache. He rapes her, or as Josephine describes it, he ‘stuck his big thing in me’, which is surprising naivety from a farm girl who would have seen dogs or other animals mating. Her sister Elke twigs that she’s pregnant because she’s not using the ‘blood bucket’, that there’s ‘no little sister with her in the bucket’. Can you hear that outraged howling? How dare a man write about rape and menstruation?

Wedde does it very well. We are not bludgeoned with gruesome details. When the pregnancy is revealed, Josephine’s parents reject her, holding her responsible for it, as was normal for the times. And Josephina herself in the early sections of the novel frets that she is somehow accountable for her own rape: Von Zarovich asked her to model the nightgown and it was while she was doing so that he attacked her.

Many women were broken and despairing from such an experience. Josephina is made of sterner stuff. She stays with a married sister in Sønderborg until after her daughter is born. Then, babe in arms, she goes to Hamburg to work as a seamstress for a kindly businessman, which is where she meets the radical journalist Wolf Bloch. At first, she sees him as a ‘strange little man in the sewing room … with pigeon chest and somewhat insolent stare …’ An incidental character describes him as ‘a Jew and an agitator.’ It is with Bloch and his sister Theodora that Josephina eventually makes her way to New Zealand, and it is Theodora who first lets the reader know of her brother’s new love. ‘They came together as distorted innocents.’

The novel is densely populated. Major characters are richly drawn with flaws and virtues. We hear directly from them in chapters that take the form of letters. The voices of Bloch and Theodora, particularly, are strong and detailed. Bloch’s associates and heroes — Friedrich Engels, Descartes, Flaubert and Hegel — are either addressed or referenced and bring the wider world into the narrative. On board the ship to New Zealand, he writes to his friend Martignetti, giving his first-person experience of the rigours of the voyage and his hopes for a new life in New Zealand. ‘Josephine and I are not husband and wife in the conventional bourgeois sense,’ he writes, ‘we are so as comrades and lovers.’ Josephina is his little bird with Kornblume eyes. After his death Wolf addresses the reader in an italicised chapter, where he debates the existence of ‘an erotics of thought’, having been carnally liberated by Josephina.

Sex, as one would expect in the establishment of six generations, plays a part and is sometimes almost risible. The adult Catharina in Wellington has an affair with a professor: ‘She liked his willy, too, though that was the word she had used when Wolf was little and she had helped him to pee with his tiny worm of a thing, and not appropriate for Hugo’s sturdy shaft with the rosy-coloured collar around its sleek emerging head.’

In either third- or first-person attempts to mimic childish speech can grow tiresome. This is Catharina on the ship:

‘She helped Tante make breakfast in the big kitchen, Tante had to do it

for Gudrun and all the others, it was her turn, Tante said, thank you Catharina

for helping to stir the pot, you’re a good stirrer! Papa Wolf would be getting

dressed while she and Tante made the breakfast, of course he had to cover up

his hairiness because it was funny. There were people waiting to make their

breakfast and some of them began to shout. Then she helped Tante carry the

breakfast to their room where the others were waiting, they had to go carefully

because the ship was rocking and also go carefully down the steps…’

An early twentieth century child is even more irritating: ‘Now I am nine adam is five and henry is two so granny says there will soon be four little wolfs. I hope the new one will be a girl because Henry is a bad wolf who treys to bite me but granny says he is just treying his teeth. Our dog curly dide we are all very sad….’

Cousin Greta writes back in her slightly older voice with information about swimming at the Te Aro Baths, having ice cream at the Pavilion in Days Bay and studying the school curriculum of the time. There is the sense here, as in a few other instances, of historical detail being utilised without any other reason than the writer wanting to include it. This is one of the greatest dangers in writing historical fiction. Later in the novel effort is made to insert material that is contemporaneous with Fred and Beth’s time — mention of our unfortunate export to Queensland, Joh Bjelke-Petersen, and the 1971 Springbok tour.

‘One could say of almost all works of literature that they are too long,’ said the nineteenth-century French writer Jules Renard. The Reed Warbler runs to six hundred and nineteen pages, which would concur with Renard. As with most very long works, though, there are parts of this complex novel that truly sing. Wedde’s evocation of sisterly love, of Sønderborg and life onboard the migrant ship, in particular, are vivid. The Kaitieke valley is alive and humming and women characters are fascinating, complex and loveable.

This novel will no doubt be long treasured by the Wedde family, just much as fictional Josephine’s Oma was by hers. It will garner also a wider readership from those interested in our nineteenth century immigrants who came from places other than Old Blighty.

This review was originally published on the Academy of NZ Literature site.