‘Byrt articulates the wisdoms of historical distance while transporting the reader into the local texture of time and place.’ So reads a section of the blurb text by Matt Saunders, Harris K. Weston Associate Professor of the Humanities, Harvard University. It’s a neat if also diplomatic capture of what makes Byrt’s account of the art moment, represented in part by the British ‘Young Contemporaries’ exhibitions of 1961 and 1962 in London, at once critically disenchanted and sympathetic. The book’s three main protagonists, New Zealander Barrie Bates (who self-transformed and -produced as Billy Apple on 22 November 1962), English artist David Hockney and English novelist Ann Quin (Bates’ sometime lover), are often represented in their own words and by implication social attitudes and self-beliefs or self-doubts. An example is Bates’ adoption of a Black American hipster persona and jargon, inspired in large measure by Norman Mailer’s ‘American existentialist’ in turn inspired, as Byrt writes, ‘by black culture and the radical object-ness of jazz’. Much of this material, the product of extended research, reads as anachronistic and often sexist (the ‘wisdoms of historical distance’ – or hindsight – bit). At the same time, however, it provides a forensic and unjudgemental narrative of ‘time and place’. Crucially, and as foreshadowed in the book’s title, this rigorously maintained binocular view opens up a fascinating account of the identity issues, the mirror-images and personas that were critical factors in the lives and practices of the book’s core cast.

The book’s adroitly chosen title derives from an extraordinary moment in Ann Quin’s 1964 novel Berg, her third, but the first she published. In it, as Byrt summarises the novel’s core identity scenario, the eponymous lead character, Aly Berg, ‘knowingly wants to kill his father, knowingly wants to fuck his father’s lover, and eventually does’. This is a variation on the classic Oedipus story that preoccupied Wilhelm Reich (The Sexual Revolution) and R.D. Laing (The Divided Self), both of whom were de rigeur theorists of social change during the 1960s. Berg reverses his name to Greb with the intention of disguising his identity from his father and in doing so creates a mirror reflection of himself. At one critical moment when Berg/Greb encounters his father having a bath, ‘The mirror steamed over.’

Following this lead in Quin’s novel, Byrt quotes a passage in Laing’s The Divided Self in which the ontologically insecure person ‘is open to the possibility of experiencing oneself as an object of his experience and thereby of feeling one’s own subjectivity drained away.’ Quin had ghostwritten Bates’ RCA dissertation ‘Pop Corn’; in one way or another, she had assisted his development of what Byrt calls ‘a framework of existentialism and Hip’, and had contributed significantly to the moment when Bates would be ready for a radical transformation. This of course would be the moment when Barrie Bates ceased to exist and Billy Apple was created, at once conceptually an art work and a person, and a repudiation of both personal history and of an art history unable to leave the past (including its provincial New Zealand location in Bates’ case) behind.

Crucially, this severing transformation also deliberately complicated and reconceptualised the distinction between the advertising/branding domains of Madison Avenue that the artist Billy Apple would work in, and those of the art world. The person now known as Billy Apple would continue to game this tension in the US with conceptually acute works that stared down his mixed successes in London, to begin with in Ben Birillo’s exhibition ‘The American Supermarket’ that opened in the Bianchini Gallery in New York in October 1964. Here, Apple shared gallery and review space with a distinguished cadre that would define what Byrt calls ‘a seminal moment in the story of American Pop’. Its members included Warhol, Tom Wesselmann and Jasper Johns, in an exhibition space designed as a functioning supermarket and an artwork in itself by the artist Richard Artschwager.

The pre-Apple, Barrie Bates companion of London RCA years, the painter David Hockney, had also constructed a public brand, in his case outing his identity as a gay man. He had also looked for ways to step away from the legacies of both academic English art history and the huge, suffocating post-war presence of American Abstract Expressionism; and, like Apple, had found the place to do that in the US, though in California rather than New York. Here, in the sunny world of swimming pools, he marked his distance from Bradford and London with paintings such as The Splash (1966). Unlike Apple, however, Hockney continued to work comfortably and very successfully within the borders of the art world – Byrt records a hint of aggrieved ambivalence in Apple’s response to his youthful RCA friend’s success. But they are still in touch, says Apple, as recorded in Byrt’s excellent Prologue, which does an essential job of civility by setting out some basic rules of conduct in establishing ‘historical distance while transporting the reading into the local texture of time and place.’

This is at best a succinct account of core themes in The Mirror Steamed Over – its richness as an account of the 1960s transformations contributed to by Barrie Bates/Billy Apple, David Hockney and Ann Quin involves a wider cast of players. For me, much of the pleasure given by the book involves its scrupulously researched and sympathetically presented profiles of other key individuals, including one of my favourite poets, Frank O’Hara, whose work as a curator and art writer was central to the emergent New York art world post-Pollock and Rothko; of another poet, John Ashbery, and artists including, in particular, Larry Rivers. Byrt’s attention to these individuals adds detail and complexity to the intertwined stories of Hockney, Bates and Quin.

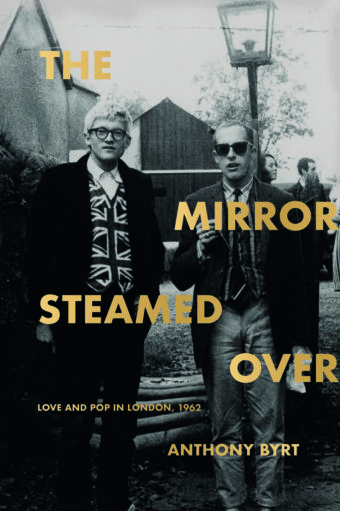

Only Hockney and Bates are depicted on the book’s cover – Hockney in what became his 1960s trademark Union Jack waistcoat and peroxided hair, Bates in a hip pair of shades. But for me the book’s unexpected surprise presence – a gift – was Ann Quin, whom I hadn’t heard of before reading this book. She probably committed suicide in 1973 at the age of thirty-seven, failing to return from a swim out from Brighton’s Palace Pier. A photograph of her by Oswald Jones, taken around 1964, appears in the image section. The photograph is of a moment of intense social pleasure and engagement, in which Quin is talking with a half-smile shaping her words, a cigarette between the fingers of her left hand, her presence emerging with warmth and vivacity from the page. I now plan to read her novel Berg as soon as I can. It is no coincidence, I’m sure, that on the page facing the photograph of Ann Quin is one of Barrie Bates, the axis of his animated speech across rather than out from the picture, Quin’s cigarette mirrored by the pencil between the fingers of his right hand. This photograph was taken in 1961, at the Royal College of Art, and but for the anachronism involved the twinned images might almost be of an exchange between the two of them. Even more than the several photographs of Bates and Hockney being laddish together, the Bates/Quin double-fold captures something of the energy of that decade of mirror images and identity transformations that constitute much of the fascination of Byrt’s remarkable book.

This review was originally published on the Academy of NZ Literature site.