Ka mahi to hopu a te ringa whero. The chiefly hand takes hold.

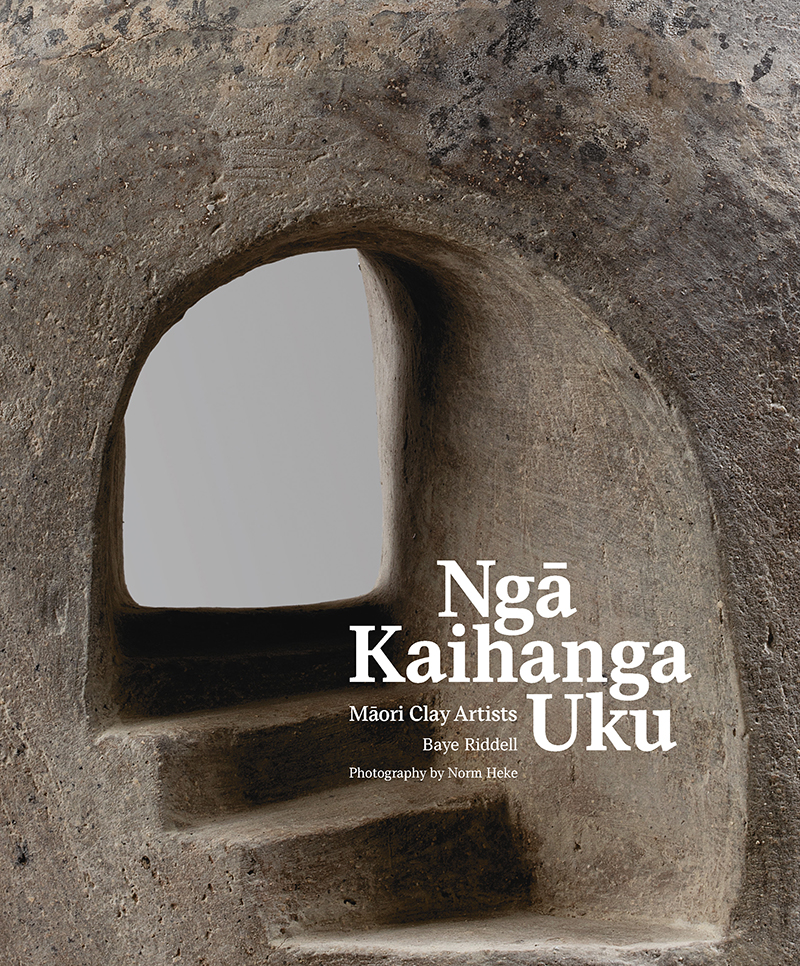

This whakatauki centres the importance of pigment, drawn from the earth, as a marker of someone of significance. It explains the way in which their practice – te ringa whero – is always of high quality, and seems particularly apt as an overarching kaupapa for Ngā Kaihanga Uku: Māori Clay Artists. Written by Baye Pewhairangi Riddell, one of the ‘tight five’ or ‘muddies’ of the group (to use Sandy Adsett’s cheeky description), this is a thoughtful, well-researched, and stunningly photographed and designed book which will make you wonder why an uku work isn’t sitting in your living room (or garden, or kitchen).

The book’s structure reflects its Māori base and the importance of artists writing their own art histories. Tā Derek Lardelli presents a karakia to bless the kaupapa, followed by a preface by Riddell. The original purpose of book – a personal history of the emergence of the Ngā Kaihanga Uku group – is tinged with sadness: Riddell had planned with project with friend and fellow clay artist Manos Nathan, but then Nathan got sick; both Nathan and Colleen Waata Urlich died before Riddell could finish the book. Darcy Nicholas picks up the story from here in the book’s introduction, identifying the original collective of Riddell, Nathan, Manos, Papaarangi Reid, Hiraina Poulson (nee Marsden) and Urlich, and later participants Wi Taepa and Paerau Corneal.

Ngā Tokorima (2003): Manos Nathan, Colleen Waata Urlich, Paerau Corneal, Baye Riddell, Wi Taepa. Credit: Norm Heke.

A short and punchy four chapters follow. The first, Mātai tūārangi / Cosmogony, covers the celestial realm, reinforcing the interconnectedness of all the elements in our whakapapa. It finishes (as do other sections) with a reminder of the power of clay for our hinengaro – in this case, that working with clay can have a ‘deeply connecting and healing effect’. The next section, Te putanga mai / Emergence, surveys the archaeological record. Māori ancestors used clay as they travelled across the Pacific, stopping when they reached Fiji, Sāmoa and Tonga. Colleen Urlich reasoned this was due to a lack of suitable clay on the one hand, and the importance of hue, although ceramics were still being made in Tonga as late as 1820, 1000 years after arrival.

Artists as researchers have a more nuanced and engaged methodology, and we as their community benefit through their creation afterwards of new works inspired by the mātauranga they discover. Artists are always researching, and increasingly also publishing their work: as books (Hirini Moko Mead, Julie Paama-Pengelly), as PhDs (Natalie Robertson, Areta Wilksinson, Kahu Te Kanawa), and as exhibitions (Nigel Borell, Taarati Taiaroa, Huhana Smith, Ngahiraka Mason). As the daughter of artists, I know it’s a crucial part of the process of making.

The idea of the starting and ending of traditions is also raised in this section. While we know about the use of raw uku to paint the body, wood and wheua bone, who knew that we had our own forms of fired uku, including for cooking fish and birds, to line small fires on waka, and most remarkably, on taonga such as nguru which were decorated with designs?

Riddell features images of these rare treasures – now in Auckland Museum – to reinforce the concept of the continuum, where ancestral ways of working uku continues through different practice. There were ‘gaps’, he concedes, rather than a continuous tradition of Māori using clay, but frames contemporary practice as the ‘re-emergence’ of an ancestral tradition.

We feel a strong sense of connection with the ancestral potters from hundreds and thousands of years past, who sat with a lump of raw clay in their hands and a picture in their minds of something they wanted to make. To us, it is as though those tīpuna have reached from their time and reality into ours to renew a lost connection and help us realise our identity in clay.

The book explores the emergence of the Kaihanga group in 1973, their exhibitions and outreach, as well as the influence of the New Zealand Māori Artists and Writers Hui, reminding us of the challenges of being Māori in our local art world. The book’s third section, Kaupapa / Values, discusses subjects, concerns and approaches common to many art forms: cosmology, karakia, whakapapa, mauri, tapu and noa. As a group, Riddell emphasises, they have always sought to ‘work with clay from a Maori perspective; share our resources and knowledge; and connect with other indigenous clay artists’.

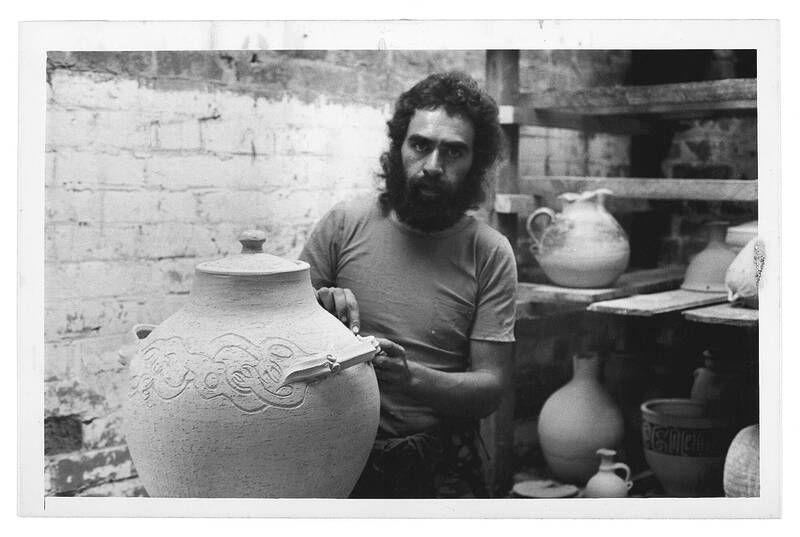

Baye Riddell works on a pot with a manaia pattern in his studio at Tokomaru Bay around 1981. Photo: Norm Heke.

They centre both whakawhanaungatanga and the challenge of always seeking new horizons. Just as carver Pine Taiapa sought out Eramiha Kapua in the 1920s to teach the art of the adze, so too did these artists look for different ways of working. In the late 80s Riddell and Nathan began what would be a lifetime of Indigenous-to-Indigenous artistic relationships, starting with artists, renowned for generations of ceramic work, from the Southwest of the US. This way of connecting has become the norm for this the group. ‘The clay connects us, the wind fills our sails, our waters cleanse and give life, and we gather as peoples around the fire to tell our stories, sing our songs and fire our pots. Mauri ora!’

The final section of Riddell’s text – Ahurewa whakaako / Adoption into ritual practice – returns to traditions, and how the artists are often driven by a cultural conundrum. To honour the beginnings and endings of the lives of loved ones means the creation of new works, which have become traditions in some whānau – waka whenua, waka pito, ipu whakanoa, kōhatu maharatanga and waka puehu.

The voices of the artists are evident on every page. Riddell’s opening sections are followed by extended biographies of Ngā Tokorima / The five founders, written by curators, whānau and artists. In the spirit of tuakana/teina, a section on Te reanga hou / The new generation follows, profiling the artists – often with tertiary training – who have ‘embraced uku as their life’. In this way Ngā Kaihanga Uku: Māori Clay Artists echoes other important Māori art books such as Mataora: The living face and the Taiāwhio collections by presenting historical context and information on both established and emerging artists.

The book is generously inclusive, acknowledging artists like Toi Te Rito Maihi who helped them along the way, and the late Selwyn Wilson and Arnold Manaaki Wilson, better known for other art forms who also worked with clay. The section on Kaitautoko / Supporters is a virtual who’s who of Pākehā potters, including Helen Mason, and Barry Brickell. This generosity of spirit extends to two very useful glossaries, one of clay terms, and another of kupu Māori. A detailed timeline of key moments features historic photographs with captions, and images of wānanga as well as invitations, programmes and exhibition materials.

It is hard to figure out if Ngā Kaihanga Uku: Māori Clay Artists is a research text with images or the other way round. The stunning new photographs by the prolific Norm Heke make the book shimmer on every page, and reinforce the breadth of practice by clay artists. This book highlights the role of artists as trailblazers in Māori culture, looking back to look forward, as risk-takers and experimental in their practice. Their hands are dipped deep in red clay, beckoning us to come forth with them on their constant journeys of discovery. As Riddell reminds us: He aha te mea nui, he tangata, he tangata, he tangata.