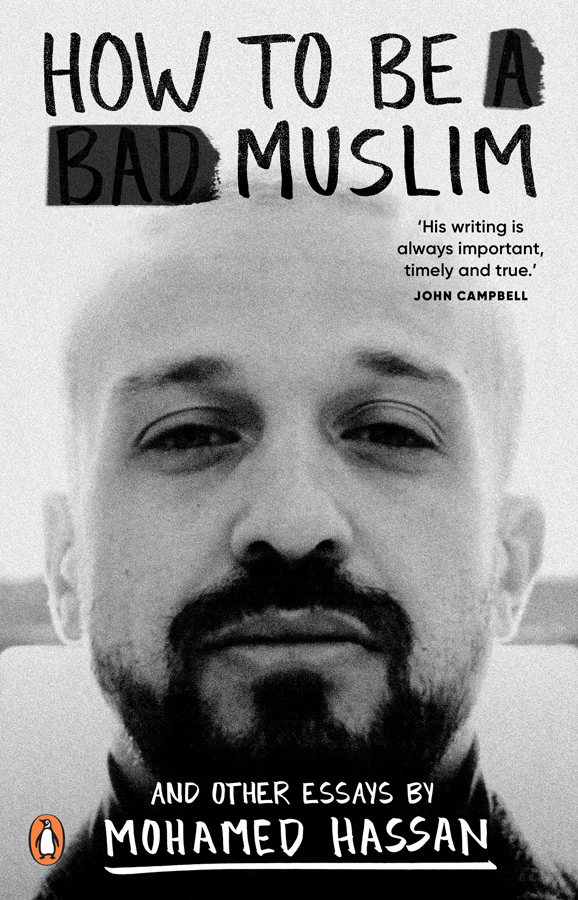

It’s evident from Mohamed Hassan’s collection of essays How to be a Bad Muslim that he has a keen instinct for a story, a talent that has also served him well in his pressure cooker roles as an award-winning journalist and champion slam poet (and whose debut poetry collection National Anthem was shortlisted for the 2020 Ockham NZ Book Awards). The essays here span from the 15 March 2019 terrorist attack in Christchurch to Middle-Eastern politics, television series Mr Robot, New Zealand’s drinking culture, the Sydney siege, questionable therapists in Istanbul and that time he auditioned for a pirate role. His razor-sharp observations of contemporary life are always illuminating, and by turns melancholic, poetic and often, very funny. I’m going to start a time capsule just so I can add this book to it.

Perhaps I’m stating the obvious, but I would like to point out that this book is not a literal handbook on how to be a ‘bad’ Muslim, or any kind of Muslim. It isn’t a dissection on Islam (although ‘The peace of wild things’ does go into the ritual of regular prayer). What it does explore are some aspects of Egyptian history, Hassan’s own family in ‘The witch of El Agouza’, ‘My country, my country’ and ‘Always watching’, and there is a strong theme throughout of navigating his way as a Muslim millennial through secular spaces. He anchors these to the familiar footholds of schoolyard bust-ups, the pain of not fitting in, the in-between zone of airports in ‘Showdown in the Kowhai Room’, ‘The last sober driver’ and ‘A stranger in no man’s land’. Just when we’re easing into their rhythm, he draws open the curtains to reveal the observers pressed against the glass, judging the feta sandwiches and basbousa in his school lunchbox, his accent and abstinence from alcohol.

Hassan is adept at building a vivid narrative through a delicate balance between beautifully rendered imagery and terse sentences:

‘As a kid who wore the question of belonging like an ankle monitor wherever I went, airports were a magical realm where no one belonged. Like me, everyone was a stranger on a journey. Everyone was seeking something they were missing, and this was the in-between place. Not heaven nor hell. Neutral. Safe.’

His mother is pulled aside and swabbed for explosives every time they transit through Australia. When Hassan is old enough to travel by himself, he finds himself detained on a regular basis because his name alone triggers security systems at the passport control desk. If you’ve ever come across his fantastic poem, ‘Unlearning My Name’, these passages in ‘A stranger in no man’s’ land lends an extra layer to the unwarranted attention to his name.

‘Subscribe to PewDiePie’ is a clear-eyed view of how the internet enabled a terrorist with his plan to upload a hate-filled manifesto to social media before he turned on his livestream and murdered 51 people in New Zealand on 15 March 2019. Hassan tracks a chilling trajectory of how social media has evolved into the beast that it is today, its platforms building algorithms to keep users feeding the monster. It’s the first essay in the collection and in a poignant piece of set arrangement, ‘Two Funerals’ is its penultimate, covering the sheer enormity of what mourners had to deal with in the aftermath of the terrorist attack. Hassan’s prose is devastating when scaled down to precise, stark detail:

From Tuesday until Friday, for five hours at a time, this is all we did. In the morning we would all stand with the bodies laid out in front of us and pray the funeral prayer. In the evening we would visit the families, Sheikh Rafat out front, telling stories about his memories of each of the departed, and describing in vivid colour the journey they were now on.

On Friday afternoon, as the final body was lowered into the ground, everyone on site broke down together. A week of leveed tears finally allowed to flood.

‘A pirate’s life’ switches tone with its funny and self-deprecating look into the humiliation of the auditioning process, and its kicker of a punchline brought a wry chuckle, despite the deflating outcome; I won’t give it away here.

‘A pirate’s life’ is a deft anecdote for its natural companion piece ‘Ode to Elliot Alderson’, where Hassan elaborates further on ‘an industry that for decades was the only source of information on Islam and Muslims for billions of people and what they saw were monsters marionette on screen to sell cinema tickets’. His argument is a compelling one, in the potted history he presents and the neat evisceration of the role that producers, directors and financiers have played in perpetuating stereotypes. Egyptian-American actor Rami Malek played Elliot Alderson in the gripping and clever television series Mr Robot, the brainchild of fellow Egyptian-American Sam Esmail. Within the complex character of Elliot and the authenticity which layers the entire series, Hassan finally feels himself truly represented on screen. That it took him until his late twenties to have this moment bleakly illustrates how Hollywood’s world dominance of the screen and its cynical paint-by-numbers approach to diversity has squeezed out other voices.

Hassan’s insights into both Hollywood and social media are intimate and meticulously examined, and it’s perhaps because of this that this reader hankered for more on his observations of the role that media have played in perpetuating stereotypes. One of his most powerful essays, ‘How to be a Bad Muslim’, does delve into critique of the fourth estate to some extent, via his experience of walking into TVNZ at the moment when the 2014 Sydney siege flooded every news channel. In a newsroom that he’d worked at for two years, the reaction of his coworkers is telling: ‘One by one, they all looked up from their screens to see me. One by one, their faces went white. First the producers of the evening news desk, then the reporters, then the cameramen, then the shift manager.’

Nobody speaks to him in the lunchroom that day. Later that year, he’s turned down for promotion for the third time because, according to his bosses, ‘I was too quiet, and it was hard to tell whether I was competent at my job.’

It’s a broad clue, as are others scattered throughout the text, such as noting the power of language and how the media deliberately uses menacing words for effect. However, this isn’t the central point of this essay, which leans more towards a sweep of the wider structures at play within not just the media, but our societies and governments, as well as how some politicians such as Winston Peters and Pauline Hanson use their platforms to stir hate. What TVNZ lost out on with Hassan being passed over for promotion, Aotearoa has gained in a fresh and rather brilliant essayist.

This review was originally published on the Academy of NZ Literature site.