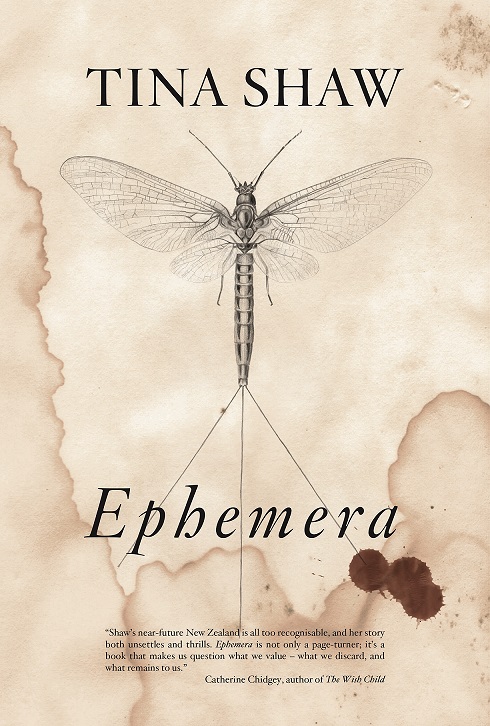

Seven years after a computer virus triggers a global meltdown, former ‘Ephemera Librarian’ Ruth embarks on a dangerous journey to source tuberculosis medication for her sister Juliana. Most of the well-paced action takes place along the Waikato River, as Ruth and companions (all saddled with their own agendas) travel by steamboat to the Huka Lodge. There are some eerie parallels to the current pandemic, including recollections of panic buying in the supermarket, and lines such as, ‘I suppose he got stuck when they closed the airports and the country went into lockdown’.

Shaw’s lively style works best when her lens is held steady on Ruth, who is vividly and sensitively drawn. Throughout the novel, however, there’s a frustrating patchiness with world building. I learned about lawlessness, empty cheese shops, and the lack of Vogels and Marmite, but the seven-year absence of electricity and broadband is barely touched on. All we get is: ‘Rumour had it various communities had got wind vanes going at a basic level and were generating electricity’. And for a trip that starts in Auckland, there’s a striking lack of Pasifika and Asian people. By the end I would’ve settled for a footnote explaining that they and all the network engineers died in the first wave of not being able to log into Netflix.

Maybe what I’m seeing as gaps in the foundation is evidence that Ephemera is ‘cosy post-apocalypse’ – a sub-genre of the ‘cosy catastrophe’, a term coined in the 70s by author Brian Aldiss in his sci-fi history Billion Year Spree. The cosy post-apocalyptic novel is unconcerned with anything beyond its own parochial gaze. In Ephemera, a pile-up of coincidental encounters with people whom Ruth either knows from her former life, or who prove particularly significant, definitely feels ‘cosy’. It’s a contrivance that stretched my suspension of belief too far, rather like the elastic waistband that gave up on my pants during lockdown.

The novel is described as ‘partly comedic’. I tried plonking down an imaginary laugh track to see if it improved the lines of one character (it didn’t): ‘I went to Lagos when I was a kid, on one of those school exchange programmes, and was kidnapped, taken hostage by a military group … They adopted me, gave me a new name.’ What definitely isn’t comedic is the characterisation of the prosperous Ngati Raukawa settlement:

The people were a mixed bunch. As we drifted in to shore, I spotted gang patches, grannies, bearded chaps, two pregnant women, a middle-aged woman with ta moko, and kids in a range of different shades and sizes. Off to one side, up a tree, a kotahitanga flag wafted on the breeze …

The people watched silently and solemnly as we pulled up near the boat ramp, and took turns splashing down into the shallow water. No arrows, I thought with relief, more a welcoming committee. It could have been ‘first contact’ all over again. I felt the echo of previous enticements offered — beads, firearms. As we walked up the ramp and onto a cleared grassy area surrounded by bush, waiting for their reaction to our arrival, I felt the urge to gift something.

I wondered if ‘partly comedic’ was a way to excuse any missteps as humour — like the ‘good-looking in a dark, Mediterranean way’ potential paedophile. Or attributing rumours of beheading to ‘echoes of Islamic State’. I get that the novel is crammed with many diabolical people, and the evilest of them all is a white dude (and oddly, apparently a dead ringer for folksy musician Bernie Griffen), but for every white person painted with a broad, villainous brush, a bunch more are granted depths of moral complexity.

‘Shaw’s near-future New Zealand is all too recognisable,’ notes Catherine Chidgey’s blurb, ‘and her story both unsettles and thrills.’ She’s not wrong. Although it’s how I imagine New Zealand would’ve been in the 1960s — no espresso, no Wi-Fi, more swingers’ parties, and POC waiting in the wings for their one-liner.

This review was originally published on the Academy of NZ Literature site.