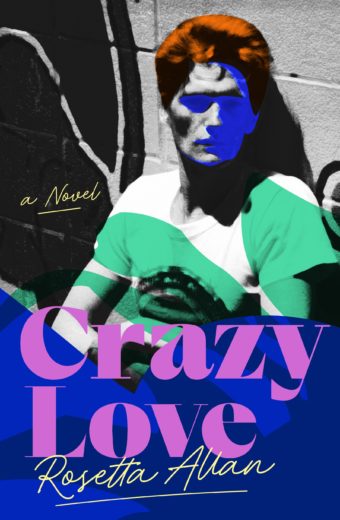

The alluring, bright cover of Rosetta Allan’s third novel suggests the ‘80s in design and colour. It features a photograph of her husband James Allan as a young man, with yellow, pink and green graphics. It also contains two very necessary words apart from the title and author’s name: A novel. Without them, the book could read as the memoir of a seriously dysfunctional relationship between two people who meet as teenagers in the ‘80s and remain married today.

The challenge with this kind of work is that the reader can’t help wondering, more than they possibly should, what is true, and what isn’t? And also, does that matter, given that we live, supposedly, in a post-truth world?

Allan goes to some lengths to disguise the true identities of the many minor characters by giving them hyphenated and often amusing names: sweet-but-sick-dollybird and rough-as-guts-forestry-man feature early in the novel, and later we meet doctor-take-your-bloody-time. Crazy-eyebrows is a literary agent, and may or may not represent a well-known, late literary agent, who had crazy eyebrows. The children of Vicki and Billy’s tumultuous union are also referred to in this way, surly-girl and eat-and-run-son, which is possibly an attempt to protect any real offspring from fallout.

After a deprived childhood, first-person narrator Vicki lands in an old building in Napier, along with an urban tribe of misfits and desperadoes, either on the dole or barely able to make a living wage. Some of them are petty criminals, or not so petty. The building is decrepit, possibly condemned, but provides a roof and party venue for many. Allan’s scene-setting is consummate, deceptively simple — her evocation of Napier of the ‘80s, the building itself and its Dire Straits inhabitants never falters. Ghastly loser-boyfriend is Vicki’s partner at this time of her life, and only because she can’t afford to survive on her own. Allan is apposite on this — how young women may find themselves forced into violent relationships just to survive. It’s a social phenomenon as old as time, and unlikely to go away any day soon.

The dynamics of the relationship with loser-boyfriend foreshadow the dynamics of the long relationship to come: Vicki is tough, but also biddable, insightful but also easily led, tender but also capable of cruelty. She is a survivor, blessed with a dry sense of humour and an instinct for optimism.

Once she falls in love with Billy, Billy takes centre stage. He is not as likeable as Vicki: keen on the dine and dash without any thought of hardship endured by small town restauranteurs; a dealer in fake cheques, reluctant to pay tax even though he avails himself of the health system; able to intimidate doctors to get the drugs he wants; and greedy for the trappings of the middle-class, buying luxury cars and houses he cannot afford. But then, as Allan so devastatingly demonstrates, he suffers from serious mental illness. At one point in their midlife, after losing a grander house and generally going down the tubes, Billy takes to living in the garden while Vicki is in the house. He uses legal and illegal stimulants, smokes heaps of dope and cigarillos, glugs back red wine and is generally abusive to his wife.

In long, bad relationships a kind of amnesia may take over, where we forget the fights and arguments. This groundhog state of mind is skilfully duplicated in the reader — as Vicki and Billy battle it out, the themes of the arguments blur and lose definition, then slip again into hard focus. Both protagonists repeatedly declare their love for one another, and whether this love is perceived as genuine by the reader will depend on individual ideas of love and of how love plays out in long marriages. Vicki is still keen on romance, haranguing her husband for declarations of commitment even while he is sectioned and under lock and key.

The most affecting, simple love expressed in the novel is that of Vicki for her dog, after it has passed away.

‘I saw the life pass from her eyes as her pupils dilated, and my face was lost to her forever. I have never experienced such enormous heaving pain before, and I still feel it when I think of that last moment…’

When Billy is finally committed to a mental health facility, Vicki comes home and worries about a cat she left behind years ago in Napier, and communes with the spirit of her dead dog, rather than fretting about her sick and dangerous husband or the whereabouts and well-being of their grown children, who barely feature in the narrative.

Misery makes us selfish. Due to their fervid focus on themselves and difficult relationship, neither Vicki nor Billy are political animals. The snap election of 1984 features, but not the peace or anti-nuke movement or Treaty marches or any of the multitude of issues of the era. The earlier dawn raids feature, but only because of the secret hidey-holes found in their more downmarket house, as relics of the ‘70s.

Billy is intent on making money in the corporate world and does well, in bursts, as an advertising executive. Despite her self-castigating refrain ‘Bad wifey. Bad, bad wifey’ Vicki’s faith in him never waivers. Suddenly, after all that’s gone on, on the day he is released from the psychiatric hospital, she believes in him enough to trust his next hare-brained business venture and go with him to buy a Mercedes with money they do not have.

Vicki is a character we don’t meet so often now in literary novels. Women totally and utterly devoted to their men, no matter what, are not part of the zeitgeist. But women like her exist and likely always will. Allan winningly demonstrates the resilience and determination of that mindset, how bad relationships will drive away friends, and the isolation that comes with the dedication. ‘My Billy. There’s no one I can talk to about my Billy.’

At one point Vicki consoles herself: ‘Everyone of us has vices to get through the tough times. We seek solutions and help. Personally, I’ve tried friends, Lotto, tears, blame, prayer, sulking, hiding in closets with my dog, running away, staying in bed, a little alcohol, a lot of alcohol, marijuana, fights and storming out. All of it works. None of it works.’

An aspect of this vividly written and compelling novel that does concur with the zeitgeist is the theme of mental health, which just now is top of the pops. It also succinctly outlines the difficulty New Zealanders have in accessing mental health care, as sufferers bounce from the police to the underfunded health system and back again.

If the novel has a message, it is surely that love can conquer all. It just depends on how consumed by it you want to be, and the price you’re willing to pay.

This review was originally published on the Academy of NZ Literature site.