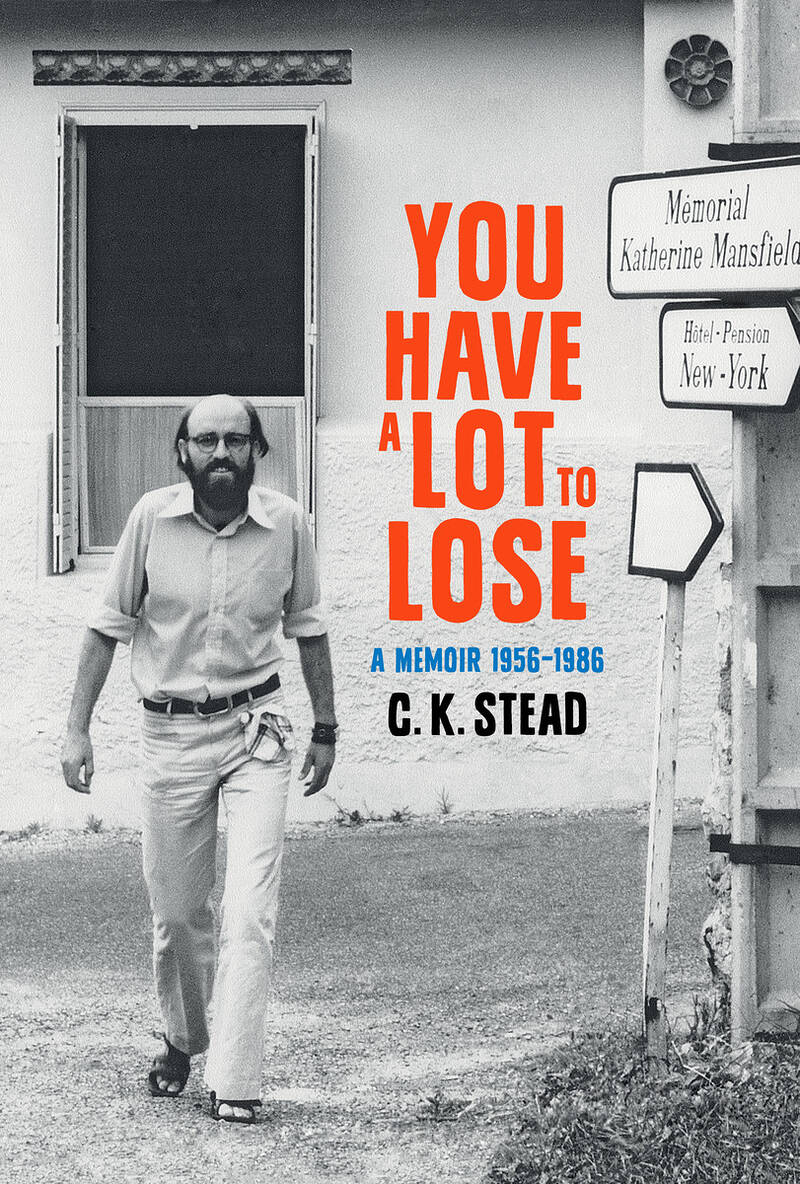

‘This is a literary biography,’ writes Karl Stead in a prefacing note to You Have A Lot to Lose, ‘a story of books and how they come about, of teaching and learning, of writers and how they interact with one another. It is a truthful account of my experience of those thirty years; nothing is deliberately misrepresented. But I have left things out, most often in the interests of economy, but sometimes for reasons of discretion, or privacy. There are significant people in my life who don’t figure in these pages. I claim to be a truthful recorder, not a comprehensive one.’

Let’s come back to things left out.

YHALTL covers the Stead years 1956-1986, from the end of the first volume when he first left NZ aged 23, to a teaching job in Australia and on to Bristol to research his bestselling critical work The New Poetic, up to the year he left teaching English at the University of Auckland to write full-time. (A third volume, which he originally planned to leave perhaps to later biographers, covering the last 34 years, will land sometime next year.) Literary biographies must by necessity shine a light on the writing. Does YHALTL do that? In spades. Stead freely acknowledges how he’s employed people from his life as characters in his fiction and poetry. A version of the entertainer Barry Humphries appears as Julian Harp in the story ‘A Fitting Tribute’, members of a Titirangi/west coast ‘party set’ find fictional form in The End of the Century at the End of the World, fishing trips with Keith Sinclair inform Smith’s Dream, a house since lost to the Grafton Gully motorways appears in a story, the background of a Sydney writer friend goes into a character in The Secret History of Modernism. And the literary and academic worlds around Stead are easily and vividly revealed, his fierce determination to make a mark, his aspirations and hurdles, his friends and rivals. We hear about the craft, the fickle muse (‘the cupboard was bare’) and the fear of not being able to reproduce the act of writing a successful novel, the ceaseless labour to improve it to make something lasting. A familiar refrain in Stead’s critical writing is an eschewing of theory and the search for clarity, plausibility, readability – all genuinely fascinating material for students of writing and NZ literature.

Through the pages slip the giants of those three decades, most of whom can be recognised with a surname: Curnow, Sargeson, Shadbolt, Duggan, Frame, Tuwhare, Baxter, Adcock, Kidman, Glover. And stars from elsewhere: AS Byatt, Claire Tomalin, Karl Miller. And artists of the time too. ‘When I look around our house now I see so much evidence of that period, not only the books our friends were writing but their paintings – McCahon, Hanly, Hotere, Binney, Henderson, Woollaston …’

How many New Zealand writers, though, require three decent-sized volumes for their memoirs? Writers usually live boring lives – they sit on their backsides and dream. But few have spent no entire southern hemisphere winter at home for 30 years, first cruising then jetting off to lecture here and there on Yeats or Eliot, have lived to nearly 90 with a prodigious memory and diligently kept a diary and most of their letters to a roster of illustrious friends. From this distance, Stead acknowledges late in this book (speaking about literary prizes), he must have appeared like a hyperactive child, ‘writing poetry, fiction, non-fiction, a professor and not-a-professor, opinionated and clamouring – in your face and a pain in the arse’.

About that ‘truthful recorder’. Thanks to what he accepts is his ‘combative’ nature, Stead has over the years got backs up all over the place. His refusal to toe the line, his public squabbles, his insistence on England as a key component of our ‘education, reading, history’ and some perhaps insensitive cultural comments at times have found him branded ‘anti-Maori’. Some novels found him accused of ‘fictional revenge’. Even his – quite understandable – keenness to tout glowing reviews from overseas over sometimes lukewarm reviews here. Much of this is in YHALTL.

What is clear is that Stead appears constitutionally incapable of soft-soaping. As he says about one writer’s stories, some were ‘remarkable, extreme, and of their kind quite unmatched in New Zealand fiction; and that so much of his other work, by comparison, was conventional and static. I felt I could not make one point without the other.’ [My italics]

Although he does accept now that he might sometimes have been too fierce in his pursuit of such unvarnished honesty, and perhaps should have opted for what another character calls ‘heavily scented brickbats’: ‘I took literary criticism very seriously. Indeed, the somewhat ruthlessly analytical reviews I had been sending home to Charles Brasch for Landfall were taking it, or myself, perhaps too seriously. It was not that my breakdown, for example, of the elements in Alistair Campbell’s poems was wrong, or even unfair; but it was unkind – and it would have been better if I could have somehow also built into it an acknowledgement that, before cool analysis set in, I had been charmed and moved by the poems I was now taking apart.’

The late sixties saw Stead embrace the view that serious writing and politics were inseparable, speaking publicly against the Vietnam War, being arrested after running on to the field to stop the 1981 Springboks game in Hamilton, condemning the Rainbow Warrior bombing. ‘These were the years when I discovered that I was radical politically and conservative academically, a division which felt quite comfortable and reasonable, but which at times made me the object of wrath from one side or the other, and often from both.’

Perhaps he’s too sensitive to criticism himself. When Janet Frame (‘entirely sane, but that it was as if she lacked one layer of protective skin – like an extremely sensitive and timid teenager’) wrote a story that cast Karl and his wife Kay in a poor light, he took severe umbrage. ‘Alan is a first-class honours student, swimmer, tennis and chess player. Sylvia is a librarian. There is an unwanted pregnancy and a termination. Gradually (the story is twenty-six dreary pages long) Alan’s poetry is subverted by academia and the marriage. He loses his hair and becomes an arid academic critic, while Sylvia resorts to growing dahlias. There are no children. Their life is barren, and all that is left between them in the final paragraph is a nameless fear.’ Perhaps worst of all, it is not a good story.

A driving force for Stead was always the health and growth of NZ Lit. He helped the university work towards getting New Zealand writing recognised and gradually established in Auckland’s English Literature courses. ‘[W]riting in New Zealand was never far from my thoughts. I told Sargeson that working on Yeats had given me “the conviction that a great literature could grow up in NZ if only our literary world would grow more self-conscious, more critical, and more confident”.’

There is infidelity. Stead writes about an affair of some length with a student, Jenny North, she 20, he 38. There was no coercion or harassment, he is quick to say. ‘We were two adults equally smitten, for a long time hesitating silent and embarrassed on the brink of saying so. She had been our baby-sitter since 1970 and at sometime early in 1971 the words were spoken and the sexual rapport which had been simmering took us the next small step for a man and the giant step for mankind of a moon-landing.’

Still some awkwardness perhaps, as this is a rare slice of cheese in the book. How about this from 1980?

‘When the conference ended I had no idea whether I would ever see Ulla again. She was my incandescent Dane, my excitable Viking and the representative charge to which I would always have to plead guilty. When she appeared as Uta Haverstrom in my third novel, The Death of the Body, she was the sexual puritan who keeps the unnamed narrator at a proper distance. In this the fictional Uta differed from real Ulla.’

Stead’s wife, a constant background presence, comes across as intelligent, passionate and formidable and part of an unbreakable duo. ‘When Kay detected clear signs [of Jenny] and asked questions there were no denials. Foolishly perhaps, I felt the whole thing was so important we had to share it, as we shared everything — as we had shared the fact of my brief but significant infidelity with a colleague in Armidale [his first academic posting]. But this was more serious, and the result was tears and anguish, and resolutions accepted also by Jenny, that our affair must stop … In my novel The Singing Whakapapa there is precisely this situation. The affair is discovered, acknowledged, and resolutions made.’ They were not kept.

Jenny, who has since died, made appearances in some form or another in three of Stead’s novels and one novella, including the second wife of Harry Butler in The Death of the Body.

What does YHALTL reveal of Karl Stead the person? A man of integrity and humour, a loyal and generous friend, a doting father. He was not a seeker of power, he says, in fact was somewhat shy and doubting. ‘I had never been one of those for whom the expectation of success was imprinted. Success always came as a surprise, failure as a disappointment but not really an embarrassment.’

He writes: ‘Katherine Mansfield tells herself somewhere “Risk! Risk all!” I was not a risk-taker. I was scuttling home to safety – I thought; but also to something I’d thought I wanted most for myself, a lectureship in the institution that had seemed to open new worlds for me; and perhaps in due course a significant place in the making of a New Zealand literature.’

Yet he did risk a lot, not least his family, with his driving ambition, that radical honesty, the infidelities, the regular departures overseas – including at least one xmas and wedding anniversary.

Thanks to the letters and emails, Stead’s is far from the only voice here. Yet as I came to the end of this book, a handsome hardback with excellent historical photos and helpful chapter postscripts, effortlessly readable — that prime virtue in the Stead rule book — I couldn’t help but imagine an annotated version with the notes of its many characters in the margins. Why did you do that? Did you really think that of me? Did that really happen like that?

This review was originally published on the Academy of NZ Literature site.