Richard von Sturmer’s latest book is a collection of travel writing originating from his role as writer-in-residence at the University of Waikato in 2020. Prose, verse and photography are used to record the author’s impressions over twelve months. He describes it as neither a travel guide nor a diary, but a ‘poetic exploration of a particular region’ – in this instance, the small towns and geographic features of the Waikato.

The University of Waikato in Hamilton is the physical starting point for many of the writer’s excursions to Morrinsville, Kihikihi, Taupiri, Putaruru, Huntly and beyond. The physical nature of the travel and the residency requirements shape the book, and the author’s impressions and responses to what is encountered are down to the author’s ‘operating principles’, being to write about ‘what was of personal interest and touched him at a deep level’. Still, the conventions of ‘travel writing’ are unavoidable, including assistance, directions and humour from knowledgeable locals.

Over a cup of tea I outline my writing project for my year in the Waikato. Tom knows of my wish to visit Maniapoto’s cave and says he will make the necessary arrangements. A week later this turns into a road trip with Tom taking time out of his busy schedule to show me places of significance for Ngati Maniapoto.

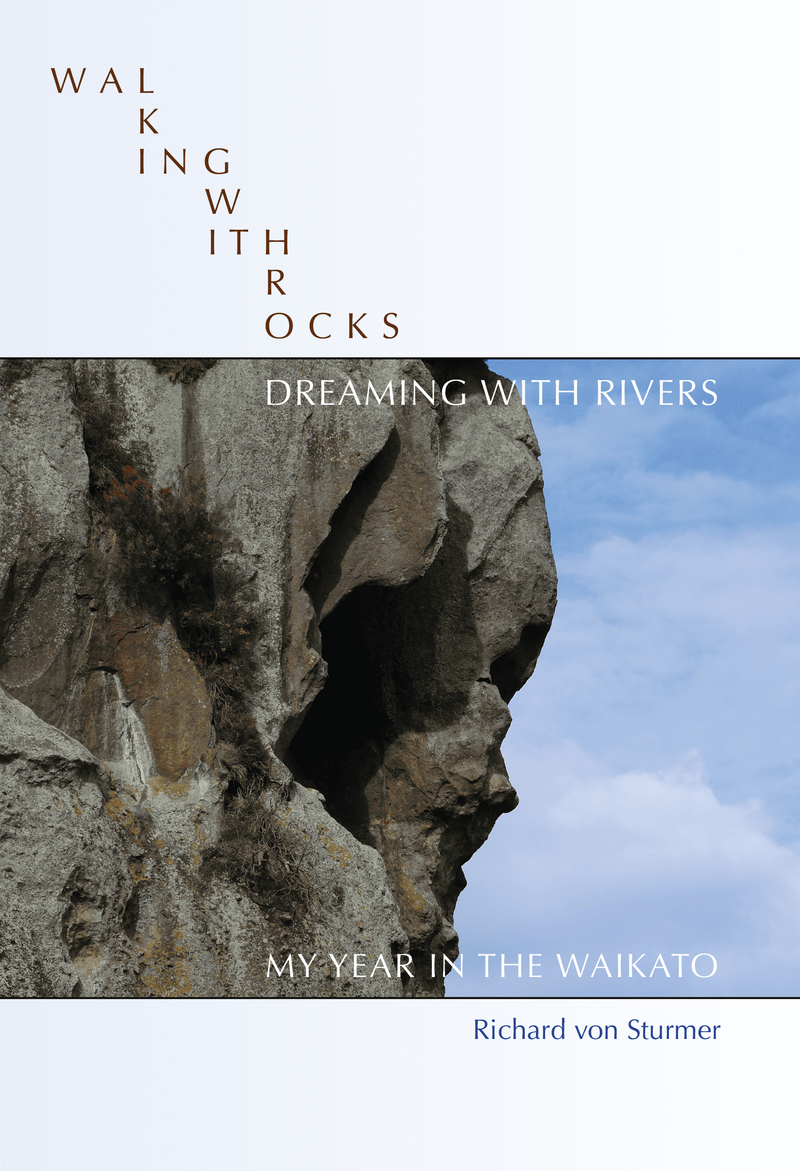

The book’s design maintains a comfortable notebook aesthetic, and over ninety photographs are included around haiku-like verse – by the author and other poets – and von Sturmer’s observations and accounts. The images successfully radiate at the same frequency as the prose and verse. Von Sturmer includes some photographs from other times and places, though this isn’t always possible:

During my childhood, each summer on our way to a fishing lodge on the shores of Lake Taupo, my father would stop in a pine forest…and before resuming the trip, my father never failed to take a photograph of the lake. Each visit felt like a new beginning. Although I’ve searched through boxes, I can’t find those photographs, and the lake itself had disappeared from the side of the road, lost somewhere among the pine trees.

This recollection connects with his earlier autobiographical book This explains everything (2016) and the particularly evocative writing that is The Dream of my Father. The idea of lost photographs is consciously inserted and the Walking with Rocks images are uncaptioned. The images dreamed and lost possess as much emotional weight as the ones actually used.

The image subjects range from existential mundane to tourism icons. There are photographs of tourist sites in Kihikihi as well as the abandoned Tokanui mental hospital. A black plastic hair comb in a leafy puddle and the remains of a fire find their own, deserved places among images of volcanic cones and watery landscapes.

Walking with Rocks, Dreaming with Rivers is also an exploration of identity. In Piopio von Sturmer glimpses a painting of Andreas Reischek, and narrates the story of that now-disreputable 19th century bird ‘collector’ and grave robber. Reischek was Austrian, and Von Sturmer reveals that his own Austrian surname is not a name of family descent, but one that was adopted.

Much of the book was written in 2020, the year Covid impacted on New Zealand society and daily lives. To control the spread of the disease, road barriers were created between regions throughout New Zealand, and there were weeks of lock down, when much of the population would remain at home. These restrictions not only affected the way travel was conducted: people had a new consciousness of what it was to have opportunities to travel at all, and some reflected on their meaningful encounter with pre-industrial silence.

In the early parts of the book the author is stranded in Auckland, his year in the Waikato stalled. Contemplation of mystical mountains and natural rock formations coexist with a real-time focus on death tolls and on wearing masks in public places, on often uncannily near-carless roads and their checkpoints. In a detached mannequin head found on a road von Sturmer sees a symbol of the ‘eerie, nearly-hallucinogenic world we had entered’.

He is a self-contained traveller, providing a personal – almost nineteenth-century – vision of places in the Waikato and imparting them with a vital strangeness and exoticism. The rail barriers and signal lights in Te Kuiti suggest the films of Japanese master Ozu. A sunset on the Piako River near Morrinsville transports the author to a painting by Gustave Moreau. Auckland becomes a destination from Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities. Gaston Bachelard’s book Water and Dreams is quoted at the prosaically named Blue Springs near Putaruru, a place that also evokes for the author the work of Monet, the blue smoke of Baudelaire and the pastels of Odilon Redon. Theodor Schwenk, the German anthroposophist and engineer, is quoted in response to a flight of cormorants.

The written and photographic flight of Walking with Rocks, Dreaming with Rivers concludes near the sand dunes of Port Waikato. The traveller evokes the arrival of a ghostly Tainui canoe, and rests against a tree branch, listening to the river and the distant roaring of surf. The reader is left pondering the ongatiti Ignimbrite in the cliffs, with the experience of an exceptional work of New Zealand travel writing, glinting with bright verse and resonating moments.

One Comment