It’s 23 years since Robert Sullivan (Ngāpuhi Nui Tonu, Kāi Tahu) published Star Waka, the groundbreaking collection about journeys and navigation that established him as one of our leading Māori poets. Since then, his research and passions as a writer have led him back, many times, into what Epeli Hau’ofa famously called ‘a sea of islands’.

Captain Cook in the Underworld (2002) — commissioned by composer John Psathas as a choral libretto — was a book-length poem exploring both Polynesian and European mythology. The 2005 collection voice carried my family continued Sullivan’s interrogations of the Pacific as a site of exploration and conflicting narratives, including accounts of Tupaia, Mai, Koa, and Te Weherua, all of whom sailed with Cook.

Sullivan’s work as an editor in the past twenty years can also be seen as an uncovering of voices, an attempt to map a new Pacific. Whetu Moana (2002) and Mauri Ola (2010), both edited with Albert Wendt and Reina Whaitiri, were major anthologies of contemporary Polynesian poetry in English. Puna Wai Kōrero, co-edited with Whaitiri, was a landmark anthology of contemporary Māori poetry in English. This body of work, as writer or as editor, suggests Sullivan’s wide interests as a reader, and his broad vision of Indigenous writing in the South Pacific.

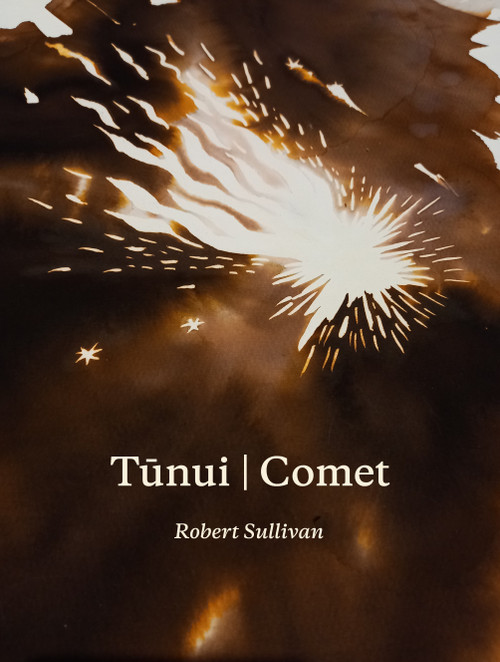

In his new collection Tūnui | Comet, Sullivan’s voice is warm and intelligent, and at times detached, the poet as observer. When he explores historical issues that impact contemporary Māori and Aotearoa New Zealand’s natural environment, the voice of the poems is measured and considered. Titles like ‘Decolonisation Wiki Entries’ and ‘Decolonising the Coastline’ suggest the late Moana Jackson’s influential essay ‘Where to Next? Decolonisation and the Stories in the Land’. ‘The Declaration of Independence’ is dedicated to Jackson himself, and reflects that great thinker’s own carefully constructed rhetoric:

… Why are we talked to about

the Treaty when it is Te Tiriti that was signed by us

and He Wakaputanga spells it out so very clearly

in black and white with our nose moko

as signatures – can you get any closer?

This piece sits almost halfway through Tūnui | Comet, and in many ways it’s the centre of the collection, an anchor for the poetry that precedes and follows it, and a clue to the collection’s main concerns: tino rangatiratanga, and the interconnected issues of colonisation, capitalism and Māori agency.

As the title of Tūnui | Comet suggests, Sullivan is still looking to the skies — ‘Clouds are habits’, the first poem begins — and is equally adept with Māori rhetoric and English poetic traditions. The sea and its deep past is still a presence: Maui hauls up land from ‘a patch of ocean black with fish’; Kupe gives orders. Many of the poems here offer a reinterpretation of our shared history, which begins with sea voyages of different kinds. The poem ‘Ah’ describes the impact of the first Europeans and the ‘new things’ they brought:

We learned to see

with spectacles,

and used our own

medicines in vials,

and ointments,

and shared them

with the sailing ships

that came to buy

our medicines,

carvings, cloaks

and food.

In a number of poems, Sullivan tries to make sense of Captain Cook, from his boyhood apprenticeships to his ‘big ego, hunger for fish and chips, plus ignorance/of what it meant setting out without blue blood.’ Of course, Sullivan is not the only writer from the South Pacific confronting Cook as harbinger: the recent anniversary spurred Tusiata Avia’s ‘250th anniversary of James Cook’s arrival’ (Hey James,/yeah, you/in the white wig’), Selina Tusitala Marsh’s ‘Breaking up with Captain Cook on our 250th Anniversary’ (‘You’re too wrapped up in discovery’), and Alice Te Punga Somerville’s 2020 book Two Hundred and Fifty Ways to Start an Essay about Captain Cook.

Here, rather than address Cook, or rage at him, Sullivan embodies him and permits Cook reflection. In ‘i wasn’t a poet for writing placenames’, he assumes Cook’s persona from birth to ‘severed burial at sea’, diminishing the historical figure’s authority by using lower case:

i was a foreman’s son who expanded

the admiral’s imperio cogito

never-setting horizons ergo sum

thanks to sharp clocks

and well-scribed logs

going to australis incognita

tahiti or the antarctic

In ‘Cooking with Gas’, Sullivan employs a playful tone, embracing both pastiche and anachronism:

I could have dined out with rear admirals

and royals. But it was the press made me do it.

They kept talking me up. By George,

I had to go out there again, and a third time too

like a Hollywood mogul.

Cook, speaking from beyond the grave, takes part in an ongoing dialogue with history — ‘what if I stayed in Aotearoa?’ — and debating his own legacy:

What if we had gained the friendship,

love and trust of the Natives,

and returned that equally

at the time, not needing

to constantly gaslight

and to make amends?

But in Sullivan’s collection, along with the Endeavour — the real thing and its replicas — there are the Interislander Ferry, surfboards and Valiants, open-air buses in Waikiki. Tūnui | Comet looks around as well as back, concerned with the many existential crises of modern Māori. This makes the collection feel both current and timely, an insightful read for any New Zealander pondering the issues of nationhood and belonging.

It’s also a personal collection, dedicated to Sullivan’s mother, Maryann Teaumihi. Some of the poems place him in his old Auckland life, like ‘Hello Great North Road’ and the poem ‘Kawe Reo/Voices Carry’ that is an engraved installation on the front steps of Auckland Central City Library. (Sullivan himself is a former librarian.) Some poems are written in and about his new home of Ōamaru, and there’s a sense of him finding himself as a Māori writer in Te Wai Pounamu. He mentions a barbeque at Hone Tuwhare’s crib at Kaka Point and visits Moeraki ‘attempting to see the same/midges and kelp as Keri Hulme’, although Covid precautions stop him from attending the first, and ‘the throng of tourists’ disrupt the latter.

The influences on Sullivan’s own identity are also multilayered and faceted, and he explores them with deadpan humour. In poems like ‘Tētahi Waerea (Prayer of Protection)’ and ‘Decolonisation Wiki Entries’, Sullivan considers his whānau history, and its bicultural origins, embracing the intersections between the Pākehā and Māori dimensions of his whakapapa, and ‘bringing the unseen chains of a grandfather clock/and a Polynesian paddle into the conversation’. Sullivan’s identities also include spirit creatures. ‘The eel in me is a taniwha’, he declares in ‘Tētahi Waerea’, referring again to this in the poem ‘Comet’, the ‘Ngāpuhi taniwha eel’ that is essential to the spiral of iwi narratives.

Sullivan is not quite in place in Ōamaru, the ‘Steampunk Capital’ — ‘You need great literacy and numeracy/to have a career in Steam subjects’ (‘Steam’) — or even within his heritage of te reo Māori: Sullivan was ‘brought up speaking English’ though his maternal grandparents were both fluent speakers of te reo. ‘In time I will write in Māori,’ he promises in ‘He Toa Takitini’, aware that this loss of te reo is an issue for many of his generation.

[…] sometimes I am reminded by non-speakers

not to use the language because it cannot be used by non-speakers

which perpetuates a cycle of disuse. It’s quite an interesting problem.

Towards the end of the collection, two long-form pieces, ‘Te Whitianga a Kupe’ and ‘Te Tāhuhu Nui’ return the conversation to the foundational importance of whakapapa. There’s work to be done, he admits in ‘Whakarongo mai’: ‘Printed words tend to stick to the page/and last longer’ than ’knowledgeable kōrero’. But Sullivan is patient rather than anxious, aware of the stretch of history behind and before us.

No worries my whanaunga. We’ll be all together after this dust

has died down. We’ll be singing along side by side in our urupa.

‘Comet’ is the last poem in the book and gives the collection the English part of its title.

I’m writing a comet

from my tupuna, Papahurihia,

which from the earth

looks like a long tailThis ancestor whose headstone

turned around overnight

So, this too is a whakapapa reference, as well as an image of light and miracle, of a message from the skies. Tūnui | Comet faces many different directions, encompassing myth, history and the quotidian, drawing on Sullivan’s rich, complex inheritance.

This review was originally published on the Academy of NZ Literature site.