There are no easy answers for Aotearoa’s struggling health system; for the long waitlists and overflowing Emergency departments; for our nurses trying to keep their heads above the water amidst dire staff shortages; and for our doctors at risk of burnout. Alongside this a debate raging ahead of the 2023 election: co-governance in the delivery of our vital public services, and how we honour our Treaty obligations. So There’s a cure for this by Emma Espiner – née Wehipeihana – feels timely, with its hard-hitting yet hopeful take on our health system.

In 2020, Espiner graduated as a doctor, arriving ‘into the Covid-19 pandemic with my tā moko on my arm, my hospital lanyard, my stethoscope and a purpose’. In the same year she won the opinion-writer of the year at the Voyager media awards, and in 2021 her podcast, ‘Getting Better: A Year in the Life of a Māori medical student’, won another Voyager award. She is currently a surgical registrar at New Zealand’s biggest and busiest hospital, Middlemore, in South Auckland.

There’s a cure for this is Espiner’s first book, and while it’s subtitled ‘a memoir’, it reads as an collection of seventeen essays, with titles like ‘Don’t Plant a Fruit Tree Over Your Uterus’ and ‘I Am Going to Demonstrate Empathy Now’. The essays form a deftly woven meditation on how we as a nation must strive for health equity. Espiner’s tales of debauched student life at Otago, her anxieties as a mother, and the trials of student doctor life are springboards into deeper conversations around intergenerational trauma, its ramifications for Māori, the importance of empathy, and how ingrained biases and the systems we’ve set up do not always serve our most vulnerable.

The book opens with ‘Pepeha’ and the marriage of Espiner’s parents. She traces her whakapapa: her mother is descended from Irish and English ancestry, of those who ‘arrived here with nothing and worked hard’. Her father’s family are from Ngāti Tukorehe, from the Tararua Range, from Tikitiki: ‘home to a cream weatherboard church on a hill overlooking the ocean, with crocheted pillows strewn across the pews and tukutuku panels along the walls’.

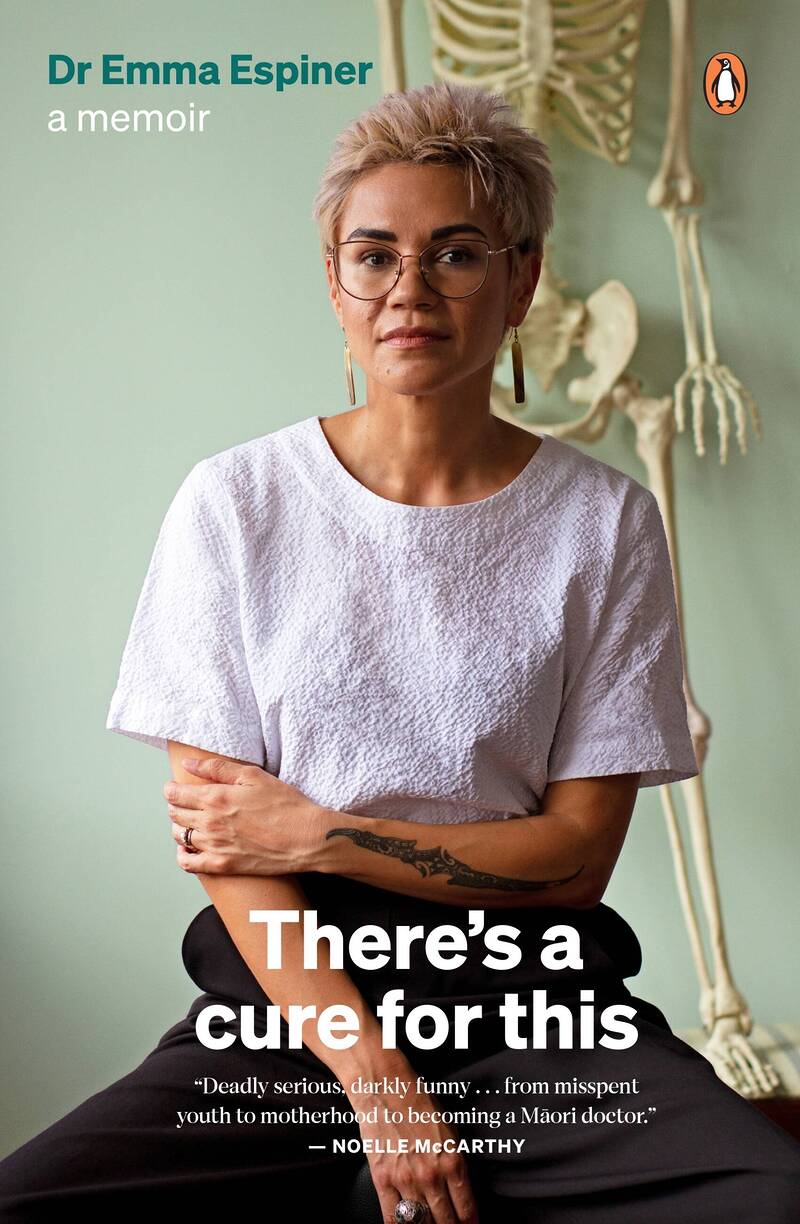

Espiner’s grandmothers are memorialised in her tā moko, a mermaid and a taniwha, that sweeps up her forearm, visible in the photo on the book’s cover. Though her parents were to divorce when she was three, to Espiner their wedding ‘epitomises how strong Aotearoa’s bicultural foundations can be when we meet each other in the middle’.

In this lies a dream: for our nation to embrace more than one paradigm, giving Indigenous knowledge the respect it deserves while true Kaupapa Māori services are strengthened to provide timely, culturally safe and effective care. Māori, Espiner argues, are well placed for this, because they have already had to navigate te ao Pākehā, employing the tools of the Pākehā while ‘dreaming differently, collectively, in our Indigenous souls.’

But Espiner’s own journey shows just how challenging it can be for Māori to balance this duality. She grew up poor, ‘in a purple lesbian state house in Lower Hutt’, her mother on the benefit, her father living ‘in a series of man-alone rentals’ that ‘always felt a bit murdery’. The adolescent Espiner was a ‘bookish nerd with an interest in boys, drinking and bad decisions’:

An outlier in our friend group once I got to high school – the brownest and the poorest, with the lesbian parents – I frequently inhabited the personality of a model child when I went to classmates’ houses. I excelled at being the good Māori, learning how to ingratiate myself with the only representatives of power who have relevance for teenagers: their parents. Keenly alert to my differences, I’d scour their reactions to get a sense of the way I displaced air in the world. I crept around the peripheries of those places with the guilt of a child who knows what it’s like to be followed around a store by a security guard.

Espiner acknowledges that ‘Once Was Poor’ is the ‘classic politician’s fable’ and that she hasn’t been poor herself for years, with the ‘day-to-day hopelessness and fear of having nothing’. Empathy, demanded of contemporary medical professionals, is ‘not a straightforward concept’. She recounts a challenge from another wahine Māori to the Māori public health organisation with which Espiner was interning: they might have ‘memories of difficult times’ but this ‘did not mean we automatically understood what a Māori woman living in poverty in 2021 was going through’.

The Māori and Pacific Admission scheme (MAPAS) aims to increase the number of Māori and Pacific health care professionals in the wake of historical biases that saw them actively discouraged from academic pursuits. Espiner was admitted to med school under the MAPAS scheme, but once again found herself in a position of feeling she needed to prove herself, having to be twice as good – ‘impeccable’ – under the racist glare of Pākehā students who believed MAPAS students were given the exam answers in advance.

The hostility of student colleagues lessened over the years of her training – full credit to Māori academics such as Papaarangi Reid and Elana Curtis, who with patience must address questions such as ‘My ancestors came here on a boat, does that make me indigenous?’ and teach our future doctors how to address their own biases.

Because of these teachers, Espiner’s kete overflows with wisdom, as well as experience: there’s ‘an ocean of stories swirling in a hospital at any one time’. She makes frequent references to her influences, including the late Moana Jackson, and a catalogue of dedicated Māori healthcare workers. The conversational tone of the essays is not that of an emotionally detached clinician standing at the end of the bed. Espiner is perched bed-side, saying: this is where I come from, this is what I’ve learned: what’s your story? It’s an invitation to listen, and it’s kōrero as it should be. In this, the book not only talks about whakawhanaungatanga, it embodies it. Espiner issues a challenge:

Part of the difficulty in establishing such a [health] service is retro-fitting kaupapa Māori onto a system which is anything but. How far can you push the existing structures to accommodate our tikanga and serve our people when those structures were designed by strangers who thought it was their duty to smooth the pillow over our faces? We were meant to be a dying race.

In this, the book is more than the personal life story the word ‘memoir’ implies. How, Espiner asks, can our current ways of working serve a people who had the eyes of their children stolen, who live in poverty, who struggle with trust in a system that sees them die, ‘sooner, sicker, unloved’? She takes us through a journey through rural Northland and introduces us to Ki A Ora Ngātiwai, a Māori health service – with its karakia and waiata, free visits, half hour consultations and ‘flat as’ hierarchy – and argues that Māori entities, instead of being dragged down by onerous paperwork and endless audits, should be trusted to forge their own paths and to self-govern as the Treaty demands.

Despite the often dark subject matter, There’s a cure for this sparkles with humour. I laughed out loud reading ‘Practical skills for the Zombie Apocalypse’ – about the trials of student-doctor life, the joy of Uber Eats and the discombobulating haze that follows night shifts. Perhaps in part due to her training, with advice such as ‘every day is a job interview’ and ‘be your least annoying self’, the book doesn’t slip into a catalogue of complaints. Instead, Espiner handles her tribulations with self-deprecating grace, and notes that most ‘people who start poor and stay poor don’t get to share their stories’.

This is not an expose of a family’s cracks like Charlotte Grimshaw’s The Mirror Book, nor is it as dramatic (or comedic) as Adam Kay’s This is Going to Hurt: Secret Diaries of a Junior Doctor. Espiner’s book treads more lightly, and readers after a tell-all of her recent split with her broadcaster husband will be disappointed. There are hints of love lost and resentments, but ultimately Espiner reveals more of her own flaws than the flaws of those around her. Her statement at the end of the book, ‘Every effort has been made to protect the dignity of the people in my life’ attests to this.

This makes me wonder if the ‘memoir’ label best serves There’s a cure for this: the switches in time and topic between essays could be disorientating for a reader expecting a life narrative. As an essay collection, it’s vivid and insightful, and serves as an exhortation to New Zealanders: We need to share power, trust Māori to run their own affairs without bureaucratic intervention, and fund Māori initiatives to achieve better health outcomes for Māori. It also a clarion call for our future Māori and Pasifika doctors who ‘are so needed and wanted,’ Espiner writes. ‘Don’t let petty envy and mean-spirited, racist attitudes dissuade you from your aspirations. Our people need you, your colleagues need you, the health system needs you.’