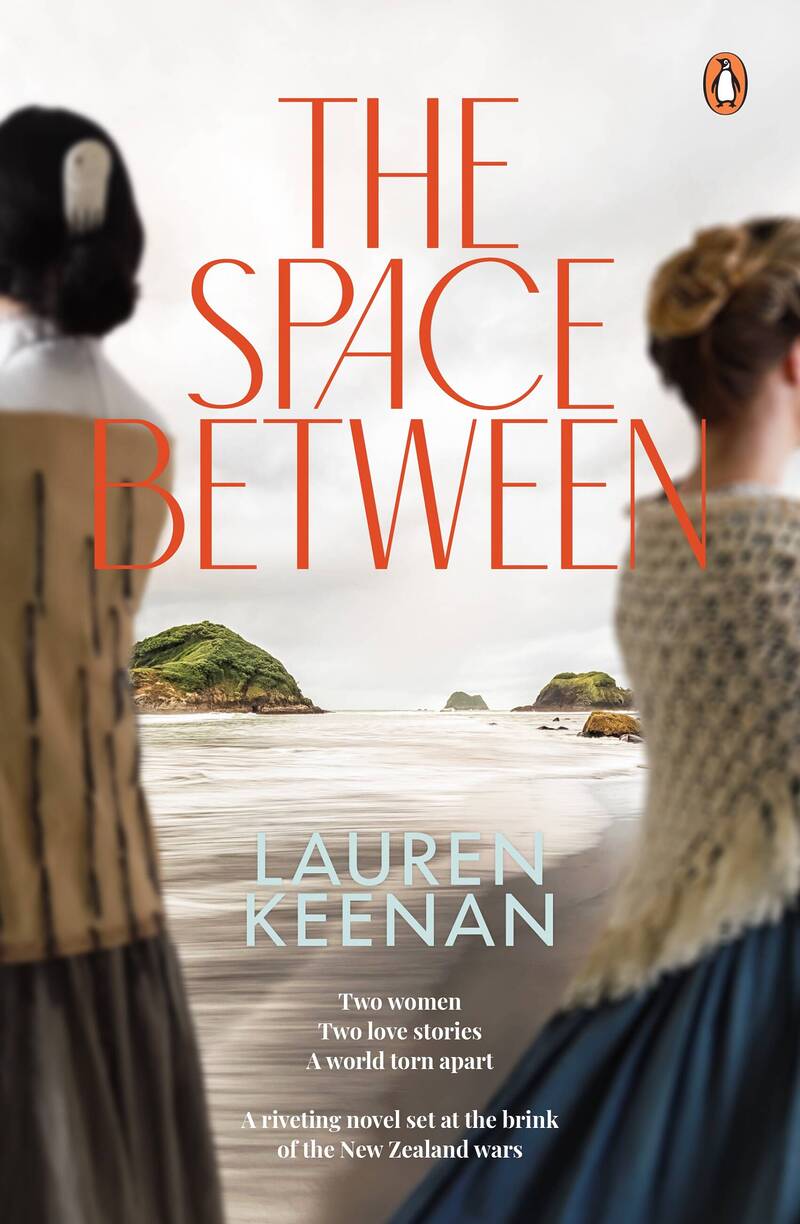

It is early 1860 in Ngāmotu/New Plymouth and the highly contentious purchase of the Waitara Block is being finalised. Pākehā are building stockades around the settlement and the militia are pouring in. Both Māori and Pākehā know that war between them is imminent. These weeks prior to the outbreak of the Taranaki Land Wars act as a historical back drop to Lauren Keenan’s novel, The Space Between. To its credit, the book does not position Māori as good and Pākehā as bad; there is personal failure as well as empathy on both sides.

The novel explores the circumstances of two women – Matāria/Minnie White and Frances Farrington – and the man, Henry White, husband of Matāria and ex-suitor of Frances, who connects them. Both women sit uncomfortably in the ‘space between’ of the novel’s title, dealing with the loss of mana and social status. Both are unloved outsiders in Ngāmotu, tolerated rather than accepted by those who are supposed to cherish them. Matāria has returned after many years as a slave for a Waikato iwi and Frances – a spinster with no dowry – is a recent arrival from London, compelled to immigrate because of family circumstances.

The exploration of this liminal space, and how it impacts on the two women’s daily domestic lives is one of the novel’s strengths. ‘I know you say the land is your place,’ another freed slave tells Matāria. ‘But we’re on our land right now and we are not free. Our people are on the brink of losing even more; soon they may have nothing. And what of people like you and me? Will our people ever welcome us? Will we always be in the space between?’

The novel’s opening chapters raise many questions – and questions keep mounting. When did the Waikato war party take Matāria prisoner and when did she escape? How long did she spend with missionaries and where? Why has she only recently returned to her iwi and why is she married to a Pākehā? How did the Farringtons lose their fortune and why is there a schism with the sister who remained in London? How did Matāria injure her leg? Who ate the damn peaches? In some instances, those answers take a long time to arrive and the slow pace of the first third of the novel mires the story in domestic detail – milking the cow, preparing food, Frances’s vegetable garden – while the story of how Matāria was taken a prisoner and how she escaped barely rates a mention.

When Keenan does provide us with a glimpse into Matāria’s past, it’s undeniably tantalising:

When she was a child, she had seen many killed: her parents; her aunts and uncles; members of the papakāinga. Some died with quiet dignity, but others did not. As a slave she had seen other slaves put to death when they were old or feeble – some murdered; some left to the elements, begging for food and water. Life and death were directly intertwined, and Te Po lurked in every space Matāria had ever existed.

The historical aspects of the novel are fascinating, including the exiling of the Puke Ariki papakāinga from within the stockade and the preparations by both factions for the coming of war. We learn that local Māori required travel passes and had to swear allegiance to Queen Wikitoria to traverse what was once their own land: Matāria is imprisoned in the New Plymouth gaol for not having one of those passes.

Both the two lead characters and the handful of secondary characters are well crafted and memorable. We can really feel the weight of unfamiliar domestic drudgery on Frances’s shoulders and how she soldiers on under straitened circumstances that include not just the loss of financial status and the fine things that went with that life, but enduring a petulant mother and useless, spiteful brother. (Spoiler alert: Guess who ate the peaches and blamed Frances?)

There’s the palpability, too, of Matāria’s pained psyche: she is excluded by the women of her papakāinga and attacked by her angry sister, Atarangi, who blames her for the death of their parents at the hands of the marauding Waikato. Henry White, the man who stands in the middle of the space between in a number of ways, is wholly believable as an Englishman who’s come to the colony and gone resoundingly native. He has eyes like those on a taiaha, Matāria thinks, ‘looking from both sides of an argument, keeping on good terms with both factions. Did that make him conciliatory or two-faced?’

Henry and Frances may have their own personal history, but this isn’t a novel about a tussle between two women over a man. Keenan is too astute a writer to fall into that lazy old trope, though some readers may be disappointed by the story’s lack of interest in what could create conflict between Matāria and Frances. Also, despite the publisher’s claim that this is a book set ‘amidst the New Zealand wars’, for nearly all of the novel shots have yet to be fired: characters are planning to fight or talking about battles fought or looking ahead to the ‘end of the war – whenever that might be’. The bulk of the novel is set in the handful of months leading up to the outbreak of the Taranaki conflict; the wars themselves take up just four pages. The Space Between does a good job of exploring a specific time in our history from the perspectives of two women, but the war itself, and other more personal conflicts, remain a little too off-stage.