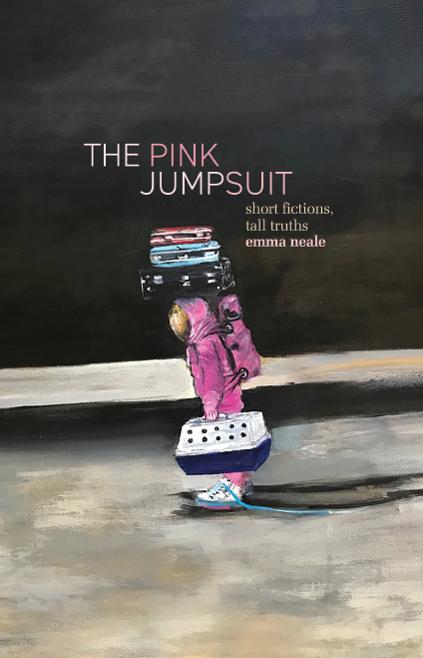

Poet, novelist, and until recently, editor of the esteemed literary journal Landfall, Emma Neale’s latest book The Pink Jumpsuit is a collection of ‘short fictions, tall truths.’ Full of the emotional potency and the heavily embroidered prose of her poetry, the collection is a contemplation of family fault lines and varieties of love. Told in tiny fragmented flash fictions and several slightly longer pieces, this collection often takes flight into the fantastical and the peculiar, to great effect.

There’s a comforting sense of balance in this collection. A feeling of sweetness even in the sadness, a grittiness to combat the saccharine, and a pillowed landing when the rug is pulled out from under you. The titular story, ‘The Pink Jumpsuit’, feels essayistic, and might be the tallest truth in the book. Placed near the end of the collection, it appears to be the skeleton key that unlocks the rest of the stories. In ‘The Pink Jumpsuit’ Neale’s preoccupations become clear — we understand her interest in fathers, broken families, heartbreak and the magic that can be found in science.

Through the father character, Neale navigates the multifaceted dynamic between parents and children. One character reimagined, the father of these stories is a workaholic, often toiling in laboratories. He’s emotionally unavailable as well as physically absent, and he haunts the characters while alive and dead. In ‘Spirit Child’, the father, with his ‘footsore, wrung-out heart’, dies suddenly, leaving behind two grown sons and a relatively new girlfriend. A year after his death, the girlfriend claims to be pregnant with his ‘spirit child’. The eldest son appreciates the absurdity of this idea; yet, heavy with regret, he feels also an outrage at the potential for losing his father once again: ‘“he’s our dad,” some small voice in me wants to say. “Ours.”’

Another version of this father appears in the story ‘In confidence’, where the daughter meets a young man at a party. Their innocent banter soon proves unnerving: the man claims to be her half-brother, his birth the result of the father’s sperm donated for scientific research. Later, the daughter understands the young man is a con man, and yet — she’s uncertain who is telling the truth, and who is guilty of deceit and betrayal. The father she’s known all her life, or a young man she feels instantly connected to? Each story dissects the unknowability of the father in a new way, and examines the impact of this formative relationship throughout their lives. The children are all searching for love, acceptance, truth. However, their inheritance is often something else entirely.

The inheritance in ‘My salamander’ is perhaps the most outlandish. The workaholic father appears again, and his scientific research comes home with him, leading to an odd genetic modification in future generations. With echoes of Ted Chiang, this story expertly slides from the straight into the strange. Neale juxtaposes the simple reflective voice with the odd dreamlike twist so that the story is both believable and fanciful. It’s one of the standouts in the collection.

Another highlight is the story, ‘Old, new, borrowed, blue’, a short fiction broken into four meditations. The final one, the brilliant part IV, steals the thunder from the first three by sheer weight of emotive power. A brief look at the relationship between Jake and Ed, this story felt like a glance into a much deeper love story, one with the same tensions and emotional depth as Annie Proulx’s Brokeback Mountain. This short piece left my mouth dry with a grief much larger than the word count would suggest is possible. Neale’s ability to create whole worlds dense with their own histories and conflicts with merely a simple turn of phrase is displayed to perfection in pieces like this.

Other flash fictions are whiplash quick and dirty: ‘I’ve never much liked choker necklaces’ is more of a punch to the stomach. ‘Courtship’ and ‘Mothian’ dance with words and evoke fleeting visions. Neale’s inner poet roams free in the shorter work, while in the longer stories her natural inclination for wordplay and subtle rhyme tends to be more hidden, like gems awaiting excavation. Every story has a final line that swirls and slides, drifting to new ideas, though the ending to the short fictionette ‘Freestyle’ is one of the best: ‘Yet — or do I mean what’s more? — at the end of every lap, each accurate, turtling turn, each small splash she gave was gorgeously private, inward, and self-contained.’

Many of the stories in the collection are ruminations about love and the consequences of broken love. ‘Worn once’ delves into the humiliating dread of the jilted bride. In ‘Stray’, the protagonist learns new truths: ‘She hadn’t understood that a person can swiftly feel sympathy, but then just as swiftly move on; that attraction can be like light passing through a prism: suddenly, exquisitely there, and then for obscure reasons, just as quickly absent.’

Neale studies love like a scientist, intent on discovering its every detail. First love, long-lost love, paternal love; her characters learn that love is far more nuanced than we initially believe. In ‘Apocalypse shelves’, a young boy discovers his grandmother’s dehydrated lover packed away for the end of the world, and realises his naivety: ‘I thought how love was somehow like pair, pare, see, sea, or even match, match. Long, long. A sound people made, and you thought you understood. But did they mean another thing altogether?’ All the characters are walking on such uneven ground, working through misunderstandings, or sometimes, in the case of one ex-boyfriend in ‘Deep liking’, the lies those closest to us might tell.

Hovering around the edges of the collection are the mystical and fantastical stories: faeries and fylgja, little men in jars and children undergoing metamorphosis. Throughout the stories, no matter how realist or surreal, there’s a biting sensation that Neale’s mining the human experience, recording it in her notebook, taking heed of the finest of details to augment her fictions. A line in ‘Trypanophobia’ sums it up best, as though Neale were talking about herself — ‘She had seen that hot, turbulent magma deep in the secret earth of every human.’ The Pink Jumpsuit opens up the human, exposing the extraordinary in our lives, our imaginations, our failures, and the ever-present potential for wonder.

This review was originally published on the Academy of NZ Literature site.