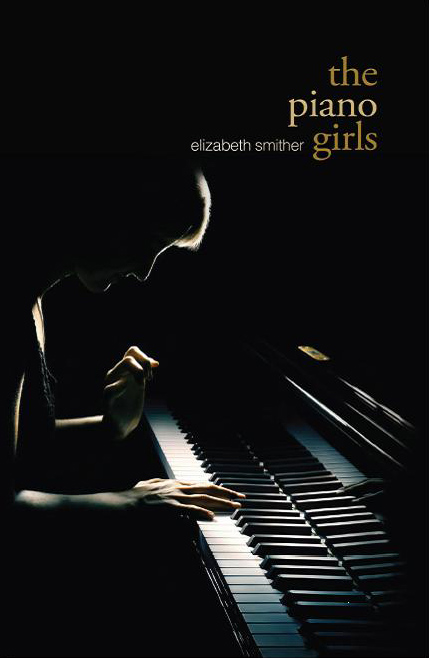

Elizabeth Smither’s contribution to the ecosystem of New Zealand literature is immense. Award-winning poetry, six novels, six short story collections, as well as memoir. Her new short story collection, The Piano Girls, which was shortlisted for the 2021 NZSA New Zealand Heritage Book Awards, is dense with linked melodies and recurring motifs, and each story is composed with the gentle touch and elegance of a seasoned, assured writer.

The book is brimming with tales — there are twenty stories in the collection, and while it might have benefited from a slight pruning of contents, this is a collection of gracefully told stories about women of a certain time. All the stories wander over similar ground, almost da capo, and the themes solidify with each repetition. Similar details appear in several stories — the eating of poached eggs on toast with honey, the study of anthropology and apes, classical music — giving the impression that, although the characters are distinct and separate, they are also connected. We don’t live in isolation, these stories assert. The echoes of the world reverberate and bring us closer together than we realise.

Relationships, both familial and romantic, is one one of these recurring themes. In the title story, three daughters commemoreate their late mother by playing a piano recital each year on her birthday. We learn the true relationship, the more honest and caring one, was with their father, and yet it is the mother they honour in this way, a feminine salute to the woman who raised them. The role of mother is further explored in the stories ‘Gravy’ and ‘Toothpaste’, and Smither worries at the burdens and intricacies of mothering, exposing hard truths. In these stories, the mothers help their daughters with little or no thanks. The mother toils in the background, sacrificing much for her children, even when they are grown, and mothers themselves.

Fathers often show their faces in Smither’s stories only to dole out money. In both ‘Money’ and ‘The Hotel’, fathers give loans along with unwelcome advice. The role of the father is almost quaint: the leather wallets opening to reveal cash notes, a relic of time before internet banking and EFTPOS machines. Though the fathers are peripheral, their impact on their children is lifelong; Jeny, the character from ‘Money’, finds the lesson learned from her father — ‘A fool and his money are soon parted’ — continues to influence her long after his death.

The opening scene of ‘Money’, when Jeny is on a dinner date with Fergus, is emblematic of many of the stories in the collection, with its subtle exploration of parents and romance. When their date is over, Fergus holds up the receipt for their meal, checking figures, ensuring meals and drinks are properly itemised. Jeny watches him, thinking ‘she had contributed so little, taken such care over her choice. No appetiser. She sat sipping water and toying with her fork while he ate fritto misto.’ Like many other characters throughout these stories, Jeny is playing a role — a role of femininity and submission. She’s careful not to make too much of a mark, to take too much. She lets the man control the situation, and waits for him to let the woman know when she is safe to be truly herself. Jeny is playing the game of love, putting on an act of femininity that she believes he expects.

Jeny’s quest for romance has a happy ending, though not every story has such a neatly tallied outcome. In ‘The Hotel’, Rosie is taken by her boyfriend to a sumptuous and expensive lodge near the mountains. She is wined and dined, and although she is aware something significant will occur on the trip, she understands it will only happen on a timeline of his choosing. At no point in the story does Rosie have autonomy over her destiny — and when the blow is dealt, it is done with Smither’s classic pianissimo gentleness. Love, as Amy Winehouse once sang, is sometimes a losing game.

In ‘Baking Night’, Antonia awaits the arrival of her most recent beau. She is worried about his expectations, recalling how a friend once told her, ‘It’s easier to seduce a woman in her own home . . . It becomes an extension of hospitality.’ Only Antonia isn’t ready to let this man into her bed. So she creates an elaborate lie in which scones, biscuits and a cake must be baked that night. She hopes the smell of biscuits baking and a cup of milk in which to dip them might subdue his libidinous desires. When reading this, one wants Antonia to tell him: I’m tired, I’m sorry, please go home. Instead, she manages him, taking care not to lead him on, while simultaneously not denying him. There is a lot of discussion about this issue today, the work women do to be submissive, attempting to dull a man’s disappointment and anger and hopefully prevent violence. While the tactic in the story is both comedic and memorable, there’s a nauseating sense of unease. The story is cleverly layered, making it a highlight of the collection.

There are other roles women play in these stories, other performances: Melissa is married to an artist in the story ‘Gravy’, and she’s playing at ‘domestic housewife’, hiding her deficiencies by having her mother deliver the perfect gravy to satisfy his appetite. Penelope, in the story ‘Tummies In, Tails tucked Under’, is performing too — as a ballerina, observed constantly. Jacqueline in ‘Ten Conductors’ analyses and dissects the performances of both the musicians in the orchestra and the conductors themselves, with their ‘little dances that could fit onto the podium’. The stories examine the ways in which we are performing for others, and the ways in which we watch others perform.

There is much to decipher and interrogate in these stories. Smither’s restrained and elegant prose delights in the lives of these women: Eloise, Julianne, Lucy, Scottie. A male point of view is included, but only rarely, for this is a book about the female experience. Domestic scenes are given weight and thought. The preparations of food (salads, pies, casseroles) becomes a talismanic force. As the title suggests, music — particularly classical music — is ever-present in these stories, for it is the soundtrack to their emotional lives. The Piano Girls is a quiet book, resonant and thoughtful; it is a collection to be savoured from one of our most admired writers.

This review was originally published on the Academy of NZ Literature site.