‘It is impossible to libel the dead; legal protection of reputation stops at the grave,’ wrote Judith Martin – aka Miss Manners – in The New York Times in 2012. ‘But is it possible to embarrass the dead?’

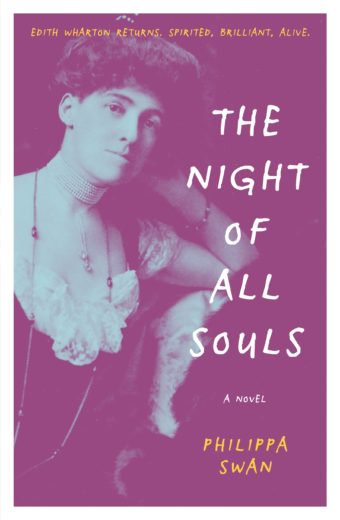

This is the central question of The Night of All Souls, the first novel by Wellington writer Philippa Swan. Swan is better known as a journalist and nonfiction writer, the author of Life (and Death) In A Small City Garden (2001). She shares a passion for gardening and landscape with the protagonist of her novel, Edith Wharton, one of the major American novelists of the early twentieth century, and the first woman to win a Pulitzer Prize for fiction. Wharton’s first book, published in 1897 when she was 35 years old, was The Decoration of Houses, and Italian Villas and their Gardens, published in 1904, was highly influential – and still in print.

Wharton was best known as a prolific fiction writer, publishing over 40 novels, novellas and story collections to both literary acclaim and commercial success. She spent much of her adult life in Europe, a cultural exile she embraced. Her career as a fiction writer is resolutely twentieth century, stretching between the presidencies of her friend Teddy Roosevelt and FDR, though her fame as a chronicler of ‘old’ New York means some might mistake her for an earlier writer. (Her Pulitzer-winning novel, The Age of Innocence, was set in the ‘Gilded Age’ of the 1870s but was published in 1920, the same year as F. Scott Fitzgerald’s This Side of Paradise, and Women in Love by D.H. Lawrence.)

The Night of All Souls opens with Wharton coming to in a book-lined room with bad lighting and comfortable chairs: this is the afterlife, and she is joined by some familiar, if uninvited, companions. Three preceded Wharton in death: Walter Berry, lawyer and diplomat, and her closest friend; blustering Teddy Wharton, her ex-husband; and Linky, her last dog. Her waspish niece (and famous landscape architect) Trix Farrand is there, to report on events up to her own death in 1959. Wharton friend Henry James doesn’t show. In his place we get a British couple from the Jamesian set, critic Percy Lubbock and his ‘black widow’ wife Sybil: Lubbock was Wharton’s one-time protégé but has betrayed her in book form, as she will discover.

The final guest Wharton finds hard to place: memory is misty in the afterlife. It’s another woman writer of the early twentieth century, a sometime fan and rival, who’s there to spoil the fun. The ghost who’s not in the room, but increasingly the topic of conversation, is Edwardian cad Morton Fullerton, a journalist on the make, and promiscuous lover – of a family member, landlady, British lords, and Wharton herself, in passionate middle age.

All of the above have been dead for many decades; for Teddy Wharton, it’s almost a century. Another of the lit-dead, publisher Charles Scribner, has provided a manuscript for Wharton to read aloud to the assembly. It’s a novella – catchily titled Following in the Footsteps of Edith Wharton – that his modern-day company are planning to publish, and he’s pilfered it for Wharton to bless or burn.

Here we have a high-concept novel that asks us to suspend disbelief in order to play along. Our protagonist feels that at the time of her death ‘the world had already consigned her to history’ and that this ‘modern novella would “sex-up” the iron-clad image of Edith Wharton’. Unlike some in her party of ghosts, she’s not unhappy about this new development, and is implicated – perhaps – in certain clues left behind that have made such a book possible.

However, much of Wharton’s dirty laundry has been swaying in the breeze since R.W.B. Lewis’s biography was published in 1975; Hermione Lee’s superb biography (an ‘800-page monster,’ as Lee called it), was published in 2007. This novel’s central conceit is that it’s only now, in the age of Twitter and TripAdvisor, that a long-dead Wharton – and her inner circle – must confront unwelcome revelations about the Fullerton affair and the duplicities of everyone’s sexual lives. Biography has already done the work assigned, in this novel, to the ‘novella’ Wharton reads aloud to her bickering coterie. So the crisis that summons Wharton’s fellow ghosts to the room never loses its feeling of plot device. That a novella would be issued by a major US publishing house these days is another imaginative stretch – especially a novella that is structured around banal blog posts.

Another straw man here is the assertion that Wharton is now obscure, which is why she is so eager to read this novella; it promises her, in egotistical ghosthood, the chance of rediscovery by a new generation of readers. But Wharton is not obscure at all: The Age of Innocence and The House of Mirth are read by book clubs as well as university classes, and Ethan Frome is a standard school text in the US. (Liam Neeson starred in the 1993 film version.) Many of Wharton’s books have been made into films multiple times: Scorsese’s 1993 all-star The Age of Innocence was the third adaptation of that book; Terence Davies’ The House of Mirth (2000), starring Gillian Anderson, was also that novel’s third film adaptation. Wharton’s unfinished novel, The Buccaneers, was a lush Masterpiece Theatre miniseries on PBS. Currently Sofia Coppola is adapting The Custom of the Country for Apple TV: this is the novel that Julian Fellowes cites as his inspiration for Downton Abbey. If fellow ghost Charles Scribner has managed to alert her to this overheated novella, wouldn’t he also know that his old imprint and its multinational overlord are still raking in money from Wharton’s own books?

Judith Martin’s New York Times piece, quoted above, was a review of the novel The Age of Desire by Jennie Fields, another take on Wharton’s unhappy affair with Fullerton, drawing on Wharton’s diaries and letters, and also featuring Walter Berry, Teddy Wharton and Henry James. Martin notes how James feared ‘posthumous invasions of his privacy’ and consigned much of his correspondence to the bonfire. He, like Wharton, was victim to Morton Fullerton’s letter-hoarding, and letter-selling. His sexual life has been investigated and re-imagined in Colm Tóibín’s 2004 novel The Master (in which James sees Oliver Wendell Holmes naked) and David Lodge’s novel Author, Author published the same year (in which James sees his cousin Gus Barker naked).

Wharton, Judith Martin contends, has had little to hide since 1980, when her desperate and sometimes pathetic love letters to Fullerton were discovered at an antiquarian bookseller’s; many were published in a 1988 edition of her letters, edited by R.W.B. Lewis, and interrogated in Hermione Lee’s biography. So The Age of Desire, Martin suggested, could be seen as ‘already rehashed gossip about a literary celebrity’ unless it illuminates Wharton’s ‘character in terms of the daily ways she reacted to the restraints of the time’.

The Night of All Souls isn’t an historical novel in the same way as The Age of Desire: in Fields’ novel, Wharton is in the moment of her relationship with Fullerton, while in Swan’s book it’s more than a century after the affair. Wharton is long dead and trying to make sense, reading the novella in which she figures, of blogs and cell phones. ‘Human passions may be eternal,’ writes Martin, ‘but social context keeps changing, and so, therefore, does the interaction between them’. This is what The Night of All Souls addresses: can privacy and fame and legacy coexist in our contemporary world where everything can be Googled and readers have TikTok-length attention spans? Is exposure worth the humiliation?

Whether Wharton accepts or rejects the novella – the logistics of which are fuzzy: this is hardly Amy March burning Jo’s only copy in the fire – is not the point. Wharton’s legacy doesn’t depend on a fictional rescue any more than Virginia Woolf’s legacy relied on The Hours, though there’s no doubt that a Sofia Coppola miniseries will boost book sales. All aspects of the conceit here, from the assembly of ghosts to the judgment of the novella to Wharton’s fears of obscurity to the revelation, to her and various dead cronies, of terrible things people did during their lives and afterwards, ultimately feel like so much scaffolding.

Swan is an informed and enthusiastic tour guide, as her endnotes attest, drawing on Wharton’s fiction as well as her diaries and letters. But the tour starts to feel prurient – secret bisexuality, adultery, a love-pact suicide, explicit letters and poems – and the research begins to intrude. Tóibín wisely chose a five-year slot of Henry James’ life for The Master. Here Swan has 75 years of Wharton’s life to wrangle and then a selection of things that have happened since Wharton died in 1937.

Unsurprisingly, there’s a lot of breathless summary to cram in events, an issue that also beset David Lodge’s A Man in Parts, his 2011 novel about H. G. Wells. This can read as glib and informational: ‘Thinking she had reached the bottom, she managed to find grace and dignity within herself’ or ‘They stayed in touch, and Edith recovered her inner self and humour’. At times this makes The Night of All Souls feel like notes towards a novel, a book that tells us too much when none of its revelations are new, or a high-speed novelisation of a biography. Wharton had complex friendships and her circle had complicated love/sex lives; everyone told lies, and some people made money out of other people’s fame, and other people’s personal lives. There’s material here, of course, but perhaps it’s already been overworked.

This review was originally published on the Academy of NZ Literature site.