Within a decade of the signing of Te Tiriti o Waitangi in 1840, much of Aotearoa New Zealand was in a state of armed conflict. From Te Tai Tokerau in the north to Waikato, Taranaki and the East Coast Māori were digging in, preparing to defy waves of colonial troops seeking to annex tribal lands at the muzzle of musket and heavy artillery.

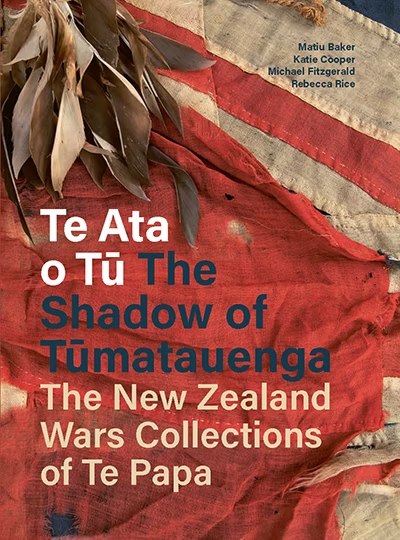

By recounting the histories of over three hundred weapons, maps, taonga, flags and photographs a senior team of Te Papa’s curatorial and historical experts have provided a thrilling and chilling antidote to what Te Papa Kaihautū Dr Arapata Hakiwai describes as ‘deliberate memory loss’. The narratives revealed by these objects from the Museum’s collection, from examples of war booty and their tangled trajectories to artworks that capture battlefield topography and drama, ensure Te Ata o Tū acts as both a much-needed corrective and fact-based lesson in our own history.

Josiah Martin, Rewi Manga Maniapoto, Ngāti Maniapoto, c.1890. Photograph, albumen silver print, 207 x 151mm. Acquisition history unknown (O.025660).

Te Papa’s full curatorial firepower is brought to bear on the period 1845–1872 when tangata whenua confronted the intent of the colonial programme and made plans to resist and fight for their land, lives and mana.

Te Papa Curator Mātauranga Māori Matiu Baker (Ngāti Toa Rangatira, Te Ati Awa, Ngāti Raukawa, Ngāti Whakaue) notes that the battle of Ōrākau ‘stands as the single largest loss of Māori lives during the wars; James Cowan estimated 160 killed and a further 50 wounded.’

‘Ka whawhai tonu matou ake ake ake!’ (‘We will fight on. Always and forever!’) is one of the great statements of defiance in the history of Aotearoa. It is the rallying cry which has secured Rewi Manga Maniapoto (Ngāti Maniapoto, ? – 1894) ‘an almost folkloric status, among Pākehā as much as Māori, for his noble dignity when facing impossible odds.’

In April 1864 Rewi and an allied group of about 300 Ngāti Maniapoto, Ngāti Raukawa and Ngāi Tūhoe warriors with many women and children were under artillery siege on swampy land near Ōrākau, south of Te Awamutu. A year earlier Rewi had expelled a Pākehā teacher for publishing material critical of the Kīngitanga, one of the events that triggered the invasion of the Waikato by colonial troops in July 1863. In Te Ata o Tū we meet Rewi kanohi ki te kanohi – face to face –in a 1890s photograph by Josiah Martin. He looks straight down the barrel of the lens, and as he promised in 1864, into history forever.

Similar 19th century images of the men and women whose actions held the line and mana for Māori provide a direct hononga (link) for those iwi Māori who whakapapa to their courageous tūpuna. For tangata tiriti and the general reader, amongst whom I hope will be future generations of students, this is a book that demands to be placed on school and university reading lists. There is nothing more instructive than putting a face to a name, another counter to the amnesia described by Arapata Hakiwai.

Charles F Goldie, The widow [Harata Rēwiri Tarapata, Ngāpuhi], 1903. Oil on canvas, 1320 x 1051mm. Purchased 1991 with New Zealand Lottery Grants Board and the minister’s discretionary funds (1991-0001-2).

.

When Goldie painted her portrait, Harata was in her dotage but as a teenager, some sixty years earlier, she and her fellow wāhine toa ran gunpowder cartridges to assist her great-uncle, Tāmati Wāka Nene and his frontline soldiers during the battles and sieges at Te Ahuahu, Ōhaeawai, Ōkaihau and Ruapekapeka.

.

Te Ata o Tu is the ideal companion for a road trip to such sites and will be by my side on a future visit to Ruapekapeka, the famed ‘bat’s nest’, south of Kawakawa and the Bay of Islands. The complex system of tunnels and trenches is still visible in the remains of the famed fighting pā, where, in January 1846 approximately 400 Māori led by Kawiti (Ngāti Hine) and Hōne Heke (Ngāpuhi) provided stout resistance against 1300 British troops armed with cannon.

.

Ruapekapeka was designed by Kawiti to even up the odds for Māori who were invariably outgunned and outnumbered. A British officer present at the battle, John Williams painted a depiction of the fierce battle in 1846. The steep palisades and heavily fortified construction of the battlement Pā are clearly visible. British officers and engineers poured over the labyrinthine structure of the Pā, as they did Gate Pā in 1864. Innovative Māori battlefield designs were assiduously studied by the British army, influencing entrenchment plans in World War I.

.

John Williams, The Storming of Ruapekapeka Pa, 1846. Watercolour and ink, 160 x 278mm. Purchased 2000 (2000-0008-1).

Te Ata o Tū takes its name in homage to the Ngāi Tahu Rangatira Hākopa Te Ata-o-Tū (?–1883) a respected tactician and battle leader, fearless in hand-to-hand combat and famed for his skill with the toki kakaroa (long-handled tomahawk). His lifespan covers much of the time period of the book, during which Māori began to comprehend the massive scale of European immigration. From 1840 the numbers tell the story. On the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi the Māori population is estimated to have been 80 000 with only 2500 Europeans living in Aotearoa. By 1860 Māori and Pākehā populations had reached parity. Ten years later Pākehā outnumbered Māori by almost five to one.

Pennant (Te Kooti Standard), c.1860, maker unknown. Wool and cotton, 1063 x 5765mm. Presented by Governor Grey, 1879 (ME000796).

‘Evidence of the political importance of flags and flagpoles is obvious,’ historian Paul Clark noted in 1975. ‘The first action by government soldiers in occupying a new settlement was to haul down the existing flag.’ Māori responded by flying their own banners, frequently co-opting British designs. As James Cowan observed in the early 20th century, ’our fighting days in New Zealand produced perhaps a more picturesque set of battle colours than those of any other land. The patriotic fire and poetic fancy of the Maori [sic] combined to work out startling effects in flag designs.’

When Te Kooti flew his famed battle-pennant in the 1860s, Māori knew that everywhere they turned, there were more Pākehā coming over the hills – almost always accompanied by troops. By this time Māori had over six decades of exposure to European religion, military systems and its attendant regalia. Te Papa’s collection of Māori military flags, pennants and standards makes for stunning viewing.

One of the great strengths of Te Ata o Tū is the assiduousness with which the authors have given agency to the Māori originators of items such as the Te Kooti standard. At over six metres in length the flag must have been quite a sight. It represents Riki, or the arcangel Michael, the protector of the faithful in times of war. His pose suggests a warrior delivering the rallying wero of the haka.

Rebecca Rice acknowledges the colonial legacy of the Museum:

The status of these flags in institutional collections remains problematic. On the one hand, they function as war trophies or as symbols of conquest, symbolising the loss or exchange of power, between contesting, oppositional parties. But they also represent Māori resistance to the divesting of that power, as well as, on another level, their acceptance of some Pākehā cultural forms to symbolise their power.

Given the scale of its subject, Te Ata o Tū is by necessity an ensemble project. As well as the work of the four lead authors, each of the five main sections features insightful essays by over 20 contributors. This diverse selection of writers, curators, historians and artists from within Te Papa and the wider motu includes Jade Kake, Athol McRedie, Lissa Mitchell, Monty Soutar, Puawai Cairns, Megan Tamati-Quennell and Ria Hall. The Te Papa team should be congratulated for such an inclusive approach at a time where publishing outlets for writers in the cultural space are being extinguished or pauperised.

These voices provide a richness of regional nuance and reflection to Te Ata o Tū. The legacy of these conflicts – on both the historic dramatis personae and their descendants today in the Waikato, Taranaki or far north – connects the contributing essays. Generations later, many iwi are still negotiating with their collective past. Jade Kake addresses this theme by detailing her own personal, whanau and hapu journey of understanding in an elegiac essay entitled ‘Despite everything, we are still here’. Kake (Ngāpuhi, Te Whakatōhea, Ngāti Whakāue) is an architectural designer and author – with Jeremy Hansen – of the recent book on the architect Rewi Thompson.

Here she keeps things local, in and around her own whenua and kainga close to the site of the siege of Ruapekapeka, delving into her own whakapapa and attempting to weave her own whanau and hapu layers of marriage, descent and displacement into a contemporary memory kete that has some logic at its centre. But this is a difficult task, sifting through snippets of kōrero – ‘a conversation outside the wharekai, in the urupā after a tangihanga, on the taumata in language I can sometimes understand clearly; other times it’s fuzzy like radio static.’ But she perseveres and reaches a place of partial resolution, ‘not necessarily healed, but acknowledged.’

It is this process of acknowledgement that makes Te Ata o Tū profound. Each object carries a story of trauma, death, loss and conflict that readers in Aotearoa who whakapapa to these spaces and times will feel awfully close to home. Many may gravitate directly to their own rohe, be it Taranaki, Rangiriri or Gate Pā at Tauranga. Holding the book together is a superb timeline to which I found myself referring constantly, seeking context across numerous conflicts and their inevitable foreshadowing. For example, on 28 March 1860 the first major battle of Taranaki took place at Waireka. In July of that year over 200 Māori Rangatira met at a great hui at Kohimarama to discuss Te Tiriti. In each case Te Ata o Tū can refer to a specific object from the Te Papa collection which illuminates these events.

Ngahina Hohaia (Taranaki, Te Atiawa, Parihaka, Ngāti Moeahu, Ngāti Haupoto), He poi manu, 2012. Recycled woollen blanket, embroidery silk, ribbon, diameter of poi 90mm, length of taura 450mm. Gift of Teina Davidson, 2012 (GH017810).

Te Ata o Tū concludes with a wonderful chapter titled ‘Contemporary Resonances’, in which we see how artists, both Māori and Pākehā, including Michael Shepherd, Shannon Te Ao, Emily Karaka and Ngahina Hohaia, have found fertile source material in the 19th century conflicts via either documentary photography of the ‘Lest we Forget’ variety or powerful evocations of Mana Motuhake. These artworks ensure the flame is eternal.

Te Ata o Tū arrives at a time when our past is entering a phase of re-contestation at a political level. It is a publication that in an age of ‘alternative facts’ makes concrete the truths these objects carry. Their lessons gather mana in the telling.