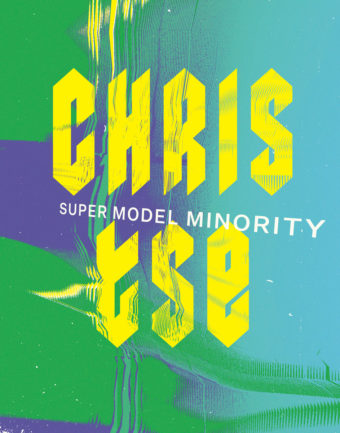

It’s difficult to read Chris Tse’s third collection of poems, Super Model Minority, silently. Just take his titles as examples: the very first, ‘Utopia? BIG MOOD!’, demands a scream. ‘Karaoke for the end of the world’ instructs towards singing. And though this frenetic volume undulates, it nevertheless joyously persists. Even a few pages before the book’s end, the reader cannot avoid the rapturous wall of text titled ‘BOY OH BOY OH BOY OH BOY’. Tse is, as he always has been, dynamic, luxurious, and fun — yet this collection showcases him as a writer of great tonal range. Beneath the effervescence, a reader finds the heavy, settled anchor of an explorative, calculating and often angry speaker.

Super Model Minority, which has become its own character in my mind, is open-armed, gracious and gregarious, the opposite of any insular and haughty idea of poetry possibly held by people outside the poetry world. Its poems take inspiration and language from Chinese-American poet Chen Chen, Aotearoa artist and poet Sam Duckor-Jones, Carly Rae Jepsen, George Michael, the Cards Against Humanity game and a bounty of other artists and musicians. Amongst the poems’ cultural references are mall cops, Korean soap operas and Girls Aloud. In Tse’s work there is always the feeling of a gesture outwards, and an acknowledgement of the work and people of whom and for whom these poems were made. This ramshackle backing chorus of borrowed voices adds warmth and breadth to the collection, while also pointing the reader towards the cross-section of identity and lyric Tse provides on every page.

The collection’s title is, of course, a clue to that cross-section. There is the excess and shine of the super model, melded to the cultural construction of the ‘model minority’, the homogeneous expectation of Asian immigrants to prove themselves as hard-working and intelligent. In these poems, Tse dissects some of that expectation, alongside the historical and current injustices faced by the queer community. It is not work done quietly; there is nothing hidden about Tse’s preoccupation with these themes. Indeed, as a whole, the collection does not shy away from the transparent expression of thought or feeling. The first sentence of the book’s first poem reads, ‘I will use my tongue for good.’ The reader knows, then, from the very start, that what they are to read has been charged with responsibility and moral motivation. It takes stamina for a poet to keep this kind of declarative work going over the course of nearly 100 pages, but Tse does it elegantly and buoyantly, injecting a lyrical bounce (‘I am not an exorcist—I am a sympathetic / vomiter’) and throwing a handful of stubborn glitter into an explication of racism, as in ‘Wishlist – Permadeath’.

There’s a conspicuous rotation of forms within this collection. A reader finds prose in standard paragraphs and verse in standard couplets and strophes, and then there are page-wide slabs punctuated by slashes or blank space, long-lined verse in islands scattered down several pages, and, in the poem ‘A flag’, two pages of prose segmented to echo the segments of the pride flag. This playful and various formatting isn’t new for Tse — his previous two books play in the same way. Still, it’s a technique that draws attention to itself. The pieces in more structured, paragraphed prose read as lyric essay, as in ‘Super model minority — Flashbacks’, with typographic punctuation to signal new sections. And still here there’s room for poetic play, especially in the gaps between sections: a paragraph about teenagehood is followed by one about generational trauma, and instead of feeling whiplash, a reader can leap with Tse through these discrete yet interconnected explorations of an identity under attack.

There were moments I questioned the form chosen for a particular piece, however. Perhaps ‘Version control’ would’ve found a little more fluency and momentum if it were laid out in prose; and Tse’s use of couplets in several poems — their ability to tense the sentence, leave me hanging — was so delectable I wished he would’ve used them more. Then again, perhaps I only wanted these things because my eyes had been treated so well by all the visual flitting and stretching I’d already been given.

Tse uses the ‘we’ and ‘us’ pronouns abundantly throughout this collection, another way of tying his story to those of his ancestors, peers, inspirations, and readers. It serves the poems powerfully, it rallies and includes, and yet I think the strongest poems here are ones where the ‘we’ slips away to make room for the ‘I’. When Tse’s lyricism becomes singular is when it is most electric. This oscillation between first-person plural and singular is clearest in ‘Portrait of a life’, a poem written after a series of participatory artworks by Félix González-Torres. Like González-Torres’s works, this poem is both for the self and for the world:

I believe the seasons of love …. will give us our direction even as

they decay . one after the other and we slip … from our foundations.

I have no name for it . but I know it like the gasp ..in my right knee

after a run . I want to prove many small things . simultaneously

There is a community and boldness in the ‘our’ of ‘our direction’, and when it succumbs to the trepidatious, needy ‘I’ wanting ‘to prove’, there is a wave of vulnerability that washes over the reader. We want to give this speaker everything, because we are there with him, alongside, carrying the same flag.

Super Model Minority is a collection about love, brokenness, history and the future, and the celebration and commemoration of all these things at once. These are Tse’s inescapable themes, and the book does not shy away from displaying, dissecting, and playing with them on each page. There is a refreshing clarity in these poems, in their speaker who comforts and calls together its readers, always challenging and not succumbing to patterns of oppression. Tse, always grasping for something open, something bright, marks out the cyclical violence and marginalisation of the groups with which he identifies. In this collection’s opening, he tells his reader that there is room for something else, though it may take ‘reverse engineer[ing] utopia’ to find it — and at the book’s close, that potential is still there: ‘The pattern is whatever you choose to see.’

This review was originally published on the Academy of NZ Literature site.