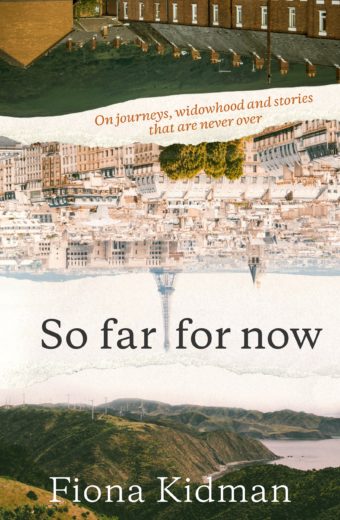

So Far For Now is a meticulously crafted collection, a series of essays that, like skilfully curated artworks in a retrospective exhibition, offer the opportunity to walk slowly and engage deeply with the huge life lived so far by that master of New Zealand literature, Dame Fiona Kidman. Framed by the measured yet moving account of her husband’s fatal fall, and the poignant yet practical contemplation of the widowhood that has followed, the collection pays tribute to a truly great marriage, the celebration and loss of which ripples across every page, but also reveals, both within and beyond that relationship, a woman of many parts.

Kidman emerges life-size from her words: spirited, adventurous, loud and constant in her demands for justice, quietly determined in her quest for truth, honest in her admission of vulnerability and of pain. The prose is similarly open, relaxed and familiar, almost colloquial in its tone and structure. Every essay is a lesson in fine storytelling, alive with incident and anecdote, character and humour, and delivered with crisp, telling detail, deftly placed strokes of colour and texture that combine to convey a deeply felt, and passionately savoured, existence. When I completed my reading of the volume, I felt as if I had just risen from a table in a sunlit kitchen, having reluctantly reached the end of a long conversation with Kidman, during which we had together laughed, argued and cried over life, the universe and everything.

And everything is in this book. Organised into five sections with titles that subtly reflect their contents, the essays deliver reflections on myriad places, people, and preoccupations of the author’s life to date. The first part, entitled Mine Alone, brings into focus the locations and human histories that have shaped Kidman’s own identity. Its first essay, ‘About Grandparents’, touches on the troubling question of home which confronts those New Zealanders, like Kidman, whose European ancestors, displaced by oppression and famine, crossed the world in hope or desperation to start new lives in New Zealand. But of course, as Kidman puts it, ‘one displacement sets the scene for another.’ And for settler descendants like the author, who have learned to acknowledge their scant right to call this land their own, identifying ‘a place to stand’ in Aotearoa becomes something of an obsession. Accordingly, other pieces in the section recall Kidman’s search for the first house of her infancy, found in Hawera, the tragicomic trials and joys of two years during which her parents attempted to farm in Waipu, and the complex relationship that she formed with that place which, along with a house on a hillside in Hataitai, she also calls home.

Other sections of the volume deliver other contemplations, and other facets of Kidman the writer, the woman, the wife. The Outsiders brings together the stories of individuals to whom Kidman has felt some extraordinary degree of commitment. In return, they have offered her excellent reasons to dig deep, and to travel far. Research into the life and death of Albert Black, subject of This Mortal Boy, led her to the streets of Belfast, and less glamorously into ‘the swamps and pines’ of Waikumete Cemetery; her unmitigated passion for Marguerite Duras carried her to Saigon and Hanoi, to the Mekong River and to Montparnasse — and another cemetery. A more local and contemporary campaign for justice is detailed in the Going South section, with a hugely informative account of Kidman’s own involvement in the saga ‘At Pike River’, her part in the battle to halt the sealing of the mine and to continue the process of investigation and accountability, and her sadness when marginalised by a new order in the movement’s leadership. Kidman holds aloft another placard in her interrogation of New Zealand’s questionable record on women’s reproductive rights in ‘Playing with Fire’, an essay in the section entitled The Body’s Sweet Ache. Opening that set is an extraordinarily intimate yet also charmingly pragmatic account of Kidman’s enduring relationship with massage, which commenced in a subterranean room in a Bangkok hotel with an experience that was ‘a kind of rapture, a removal of the self from the body, a kind of surrender.’ Though one has gathered by now that Kidman does not surrender often.

Every section except one closes with an essay, skilfully selected to align in tone and focus with its set, which focuses on a particular element of Kidman’s life as a writer. These experiences, as a teacher of memoir writing, a participant in literary festivals, a writing fellow in Otago, even as an unproductive prisoner of Covid’s great lockdown, add an enriching layer of intertextuality to the volume — Self-portraits of the Artist as Author, if you will. This New Condition, the final section of essays, is the exception to this pattern. It concludes instead with Kidman’s invaluable reflection ‘On Widowhood’, a frank and very personal exploration of the many challenges presented by this unwelcome and under-discussed phase of life, which so many women must navigate. Heart-rending and humorous by turns, Kidman confronts such issues as repelling gold diggers, dining alone, removing the ring, and, eventually, realising that there can still be perfect days. The ache of her loss never lessens, but it appears, in these final pages, alleviated by a reflective calm, perhaps part of what the author describes as ‘one of the gifts of age — a softening round the edges, an acceptance of how things have gone.’

This gentle acceptance, however, is belied by the sustained energy and appetite for life and work that emanates from the writings of this collection. There is grace, certainly, in Kidman’s reconciliation to the conditions in life she cannot change, but in no sense has she surrendered to age. On the contrary, in So far, for now, she has mastered it.

This review was originally published on the Academy of NZ Literature site.