Nearly ninety years ago, the British author A.J.A. Symons did something which may or may not have been to the benefit of later writers. With his The Quest For Corvo, he wrote the first biography to place the biographer at the centre of the story, piecing together how he came to research his subject. This was long before anybody had heard of postmodernism, but The Quest for Corvo is now often called the ‘first postmodernist biography’. Trouble is, Symons’ daring innovation has become a cliché. The world is now awash with non-fiction called ‘In Quest of This Person’ or ‘The Search for That Person’ or even ‘Finding So-and-So’. And the come-on is always the same. The author claims to be investigating the nature of his subject in new ways, which nobody else has considered. The author claims to have found new information, hitherto hidden, about his subject. And always the author invites us on his own journey, which can overwhelm the biography part.

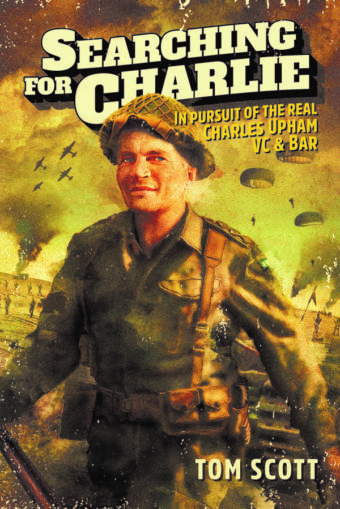

This is very much the genre of Tom Scott’s Searching for Charlie, subtitled In Pursuit of the Real Charles Upham VC & Bar. Often Scott is in conversation with Kenneth Sandford’s straightforwardly heroic biography of Upham, Mark of the Lion, published in 1962 and read by all Kiwi schoolboys of my (and Scott’s) generation. Scott says he carried Mark of the Lion wherever he went on his journey. Sometimes he quotes from it. Sometimes he corrects its minor errors (such as Sandford’s claim that Upham won a knighthood) and he tells a few salty stories that Sandford didn’t include (such as a mildly cruel prank Upham played on a POW to persuade him to be a blood donor). Most important, having convinced us that Charles Hazlitt Upham was not a psychopath, and having told us that he was essentially a modest, if determined, Kiwi bloke, Scott says that he is in quest of the source of Upham’s extraordinary courage.

Of this courage there is no doubt, well attested by official records and many witnesses. Upham was the only soldier to win the Victoria Cross twice. Scott gives credible evidence that his superiors would have awarded him more VCs if they had not been overruled. If you’re going to have a war at all, Charlie Upham was the type of soldier you wanted in the front line. He really did knock out, single-handedly, enemy machine-gun posts and strong points in the counter-attack on Maleme airfield in Crete. He really did organise defences against Rommel’s tanks on the Minqar Qaim escarpment in North Africa, and led the breakout once the Kiwis were surrounded. With all the gusto of an old Boys Own Paper yarn, Scott depicts Captain Upham rallying his men and charging forward throwing hand grenades at anything that looked like an enemy. It helps to know, as the book often emphasises, that Upham was a taciturn guy who never boasted and had a ‘defiant, bewildered, almost pathological modesty’. Better still, Upham wasn’t up himself. ‘Fiercely egalitarian, he was better than no bastard and no bastard was better than him.’ As a bonus, he could swear a blue streak, so he really is one of us regular jokers, right?

But there are big problems in the telling. Scott travelled to many sites of Upham’s war experience – Greece, Crete, North Africa, Italy, Germany. But while he tells us the sights he saw, and the scant surviving evidence of a long-ago war, little of the travelogue illuminates anything new about Upham himself. The narrative shows us that Scott interviewed many old-timers (family and fellow-soldiers of Upham) and some military historians in his research. But Searching for Charlie has only a very modest bibliography and absolutely no footnotes or endnotes to verify sources. This becomes problematical when we meet passages that read like fiction. Was Charlie Upham really sitting in a long drop in 1935, and reading a page of newspaper supplied as toilet paper, when he first became aware of Hitler’s persecution of Jews? And did he immediately jump up and shout ‘Bastards! Filthy bigoted sons of bitches!’? Maybe he did, but I’d like to see the source of the story. Elsewhere, Scott admits that some scenes are simply as he imagines they should have been, like Upham’s response when turning down a knighthood.

Scott tries hard to mitigate the fact that Charlie had a privileged childhood before he morphed into a rugged, backblocks farmer and soldier. He was the son of a wealthy barrister, resident of Christchurch, and attended Christ’s College. So we get accounts of the jolly wheezes he pulled at school, which, we are told, later allowed him to rag German guards when he was a POW. Then there is the jokey-blokey tone Scott often adopts. We are told that the words of the Horst-Wessel Lied really translate as ‘All we are saying… is give war a chance.’ I think a laugh track was meant to be inserted there.

It’s true that Scott doesn’t deny the darker side of Charlie Upham, showing that, post-war, he could be a grumpy and even threatening man. Reasonably enough, Scott suggests this could have been one effect of long-term PTSD. Even so, the sum of this book is simply to reinforce the iconic image we already had of the great New Zealand warrior. I find no new explanation of the source of Upham’s extraordinary courage, despite the declared rationale of Searching for Charlie. I’m sure it will have a wide readership and be enjoyed by many (especially males). But maybe some historians and keen readers of history who want and expect more will grit their teeth.

This review was originally published on the Academy of NZ Literature site.