Is there a medium better at expressing the universality of the human experience than the diary? There’s an inherent contradiction – and a tension – in the idea of a public diary that reveals the specific and private longings of an individual to a completely unknown audience.

In an ideal world, I might be able to say that I discovered Robert Lord (1945–1992) as a young queer playwright, seeing productions of his plays in theatres across the country. But until I was a writer-in-residence at the Robert Lord Cottage in Dunedin, I didn’t really know who he was. Through the posthumously published Robert Lord Diaries I’ve learned more about the inner life of a man dedicated to playwriting in New Zealand and the US, although theatre did not always love him back. Roger Hall, Lord writes in 1987, ‘seems to have more faith in his work than I do in mine and gets really upset when it is spurned, rejected or ignored. It has happened so many times to me that I don’t even think about it anymore.’

In the theatre, Lord was not known for his explicitly autobiographical work. ‘The hard part is to write a character based on yourself,’ he writes in 1989 about his play Boxing Day. In that ‘family drama, the “I” character, the centre, has to be someone other than me’. The intensely confessional diaries, then, are quite a departure. They begin in 1974, when Lord was travelling in the US, though by then his work had been produced in New Zealand and Australia, and he was one of the founders of Playmarket, our primary playwriting agent and publisher. Many of his scripts are available today through the Playmarket site.

Entries in the eight diaries collected here are sometimes fragmentary and episodic, often jumping in time. It isn’t until 1980 that Lord finds momentum and consistency in his diary-writing, and the last entries are from 1991, after he returned to live in Dunedin. The diaries offer insights into the inner workings of Lord’s creative process, from drafts to rehearsals.

In New York his work included the plays The Affair, China Wars and The Travelling Squirrel. The process of revision and iteration was an important one for him.

Wednesday had a reading of Squirrel that was most helpful. Act One worked very well & just needs some pruning. Act Two, after about 10 minutes (page 12), took a nosedive & while sporadically amusing was obviously not working according to plan … Friday – today – a reading of Bert & Maisy to hear rewrites. Basically loved them but need some fluffing … Each beat must be played for the reality of that beat – myopic absorption in detail.

Lord maintained professional connections in New Zealand, finally securing a Burns Fellowship in 1987, and writing scripts for the 1981 feature Pictures and the TV series Peppermint Twist (1987). However, as these diaries make clear, wherever he was living the struggle to make a living as a playwright was immense. His first play, It Isn’t Cricket, debuted at Downstage – New Zealand’s first professional theatre – in 1971 and it was featured two years later in the inaugural Australian National Playwrights Conference.

But success for local playwrights then, as now, required perseverance and resilience. The diaries articulate the complicated feelings of many artists – a desire for success, the anxieties of failure. There are financial woes and writer’s block, as well as awards, grants and quiet breakthroughs. Lord often employs an irony familiar to queer artists – ‘Life is nothing if not full,’ he wrote in 1987, after flooding the laundry; worried about being ‘overweight and unattractive’ he forces himself to go to the ‘Les Mills House of Pain’.

Emerging from the diaries is both Lord’s need and his struggle to write. ‘In a terrible state of ennui,’ he notes in 1984. ‘Am frustrated by everything – plays written and unwritten. The job. The health. The heat.’ In one entry he vows to leave New York ‘if nothing seems set in my career by the end of the year’; two weeks later he’s ‘fired up’ about five different projects. He laments his ‘financial mess’ and worries about ‘a way to get some money and also to write without being constantly exhausted’.

What would I give for a lifestyle where I could write 3 to 4 hours a day, swim, & read? A good question. Do I need to continue to receive the stimulation of NYC, would I stagnate in NZ? If it were possible to get, quite soon, a grant for a year to write there, I would find out.

As an account of a New Zealand artist trying to make it overseas, the diaries offer a tale both cautionary and inspirational, as well as context for both the playwriting culture and queer culture of the 70s and 80s in New York. The frankness expressed here reminds me of many gay literary memoirs, from John Rechy’s City of Night (1963) to Timothy Conigrave’s Holding the Man (1995). Lord’s New York is a city of ‘pornography, dirt and graffiti’, of nights at St Mark’s Baths and Studio 54, of days as a ‘shop girl’ at Le Magasin on Christopher Street. He worries that he might be

caught up in that city syndrome that can keep one busy for months only to show you that you weren’t busy at all. New York is the easiest city in the world to do nothing in – and not notice it. And being gay accentuates this. One is trapped in a ghetto of parties & hunts. Sometimes I wish I was a eunuch.

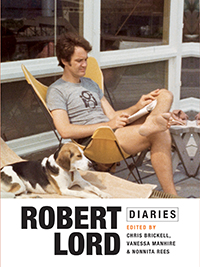

Editors Chris Brickell, Vanessa Manhire and Nonnita Rees have done an admirable job piecing the entries together with detailed footnotes and context, making sense of timelines and information not necessarily intended for publication. The book has a detailed biographical introduction and includes production stills and rehearsal photos (Meryl Streep makes a cameo), as well as personal photos of Lord, his family and friends, including his mother Bebe and editor Nonnita Rees. The most striking and candid photos, though, are of Lord himself.

Lord could be upset and angered by reviews (‘I am sick of being dumped on’) but he could be a severe critic himself. Good reviews in 1987 for his play Bert and Maisy at Dunedin’s Fortune Theatre dismay him: ‘I don’t think either the production or the theatre deserve the success’. Roger Hall’s play Fifty-Fifty (1981) ‘I did not enjoy – basically a good television show’ and Downstage, where it’s staged, is ‘now what we never intended it to be – a very competent version of the old amateur groups doing plays which seems to be daring but which really are not’. A young Anthony McCarten is ‘vague in his writing’ and his hit Ladies’ Night is ‘an awful creepy-crawly play with some good moments’.

The tone of the diaries shift as Lord deals with his HIV status: an AIDS-related illness would kill him at the age of 46. We see him deal with the realities of failing health and inaccessible medication. In Australia in 1989 Lord is ‘beginning to feel like a failure … how I usually feel when I come to Sydney’; he doesn’t begrudge the success of his friend Nick Enright, but feels despair:

I’m jealous of the fact that he is grounded in a place where he can live and work – and it is native to him. My frustrations regarding New York are that I am and always will be an outsider and now I’m an outsider in New Zealand … And now this dying business is beginning to sink in and confusing me. Just how big a failure am I? How much have I deluded myself? Will any of the plays ever really have a life?

The diaries, which began as a Proustian exercise in memory-making, transformed into an act of defiance, Lord writing to the bitter end. The last diary entries show him contending with his final finished play, Boxing Day: he was racing against the clock to finish and perfect it. He didn’t live to see that last playce staged at Circa in 1992 as Joyful and Triumphant, a month after he passed away. It is perhaps some consolation to know that the play was received to great success (including Chapman Tripp Theatre Awards for Production of the Year, Director of the Year, and New Zealand Playwright of the Year). His home in Dunedin was left in trust, and for the past twenty years has hosted writers-in-residence, like me.

Lord’s diaries tell a story of seeking and making a home, a story of belonging. He was a queer man, a queer playwright, a queer New Zealand artist with ‘an abiding ambivalence about being a New Zealander’, as the book’s introduction notes. ‘Are diaries an act of narcissism or self-torture?’ Lord asks and despite the intimacy and candour of these diaries – ‘I continue my love/hate relationship with myself’ – he may have suspected that one day publication would come. Perhaps, however self-flagellating, all playwrights are exhibitionists.