Ripiro Beach opens with a birth gone wrong, described in lucid, visceral prose. One paragraph in, when I realised what I was reading, I was hit with a wave of nausea and alarm. I didn’t think I would be able to continue with it. I held the book at arm’s length, read with one eye shut.

After birthing a healthy, full term child, Barron comes perilously close to haemorrhaging to death. She has placenta accreta, where the placenta is ‘attached to the uterine muscle, so it cannot be separated without tearing.’ Barron is rushed into theatre, given an emergency hysterectomy and infused with 15 litres of blood. Inside that moment, she understands that she is dying. She is taken into a vision of her husband and daughters in their home without her. She views them through a glass window, a vision which crystallizes and becomes a source of mental anguish after she physically recovers.

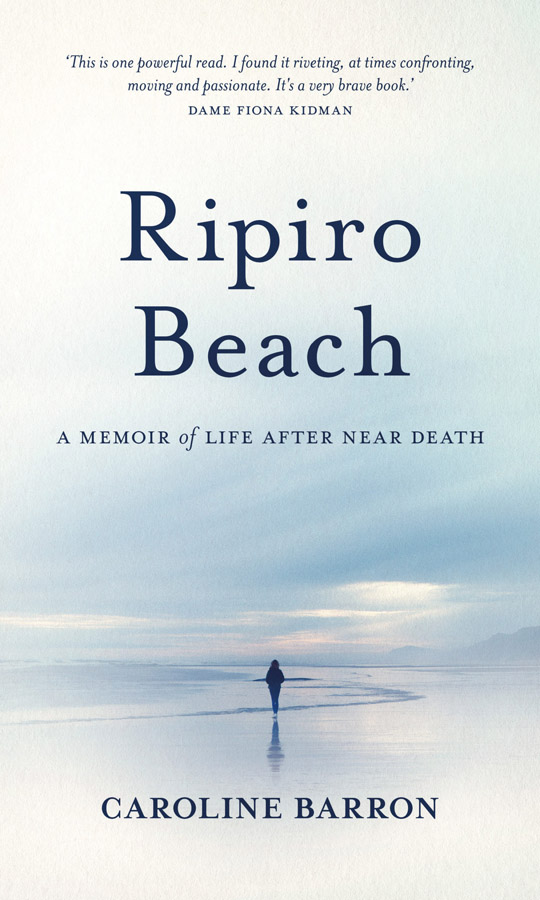

Ripiro Beach is haunted by that tapping on the one-way mirror of death. The memoir is structured around Barron’s squinting sideways at the experience for a long time, holding it at arm’s length.

Diagnosing herself online with PTSD, Barron’s first instinct is to assume she doesn’t qualify: ‘Soldiers, like Montague [Barron’s grandfather], who had seen their mates blown to smithereens on the battlefield got PTSD, I think, not privileged suburban mothers. You’re over-reacting.’ Barron is experiencing numbness, depression, suicide ideation and flashes of rage while parenting her young daughters. She knows something is badly wrong, yet nothing in the culture supports her to take her trauma in the birthing suite seriously. For several years, her energy goes into a genealogical search.

Barron’s father was adopted, and when he died of heart failure on her twentieth birthday, there were few leads towards finding his birth mother. The memoir becomes an archival detective story, with central dramatic moments based on the arrival of new papers:

‘Your request has been considered under the Official Information Act 1982,’

the cover letter says. ‘Enclosed is a copy of a prison file for Montague

Stanaway, obtained from Archives New Zealand.’

Everything Barron discovers about her ancestors bruises her: a suicide, a violent attack with a broken bottle, more heart attacks, a dishonourable war record. Barron is adept at vividly conjuring scenes from these lives in her imagination; we keenly feel how the details she discovers press on her, and distress her. These ancestors have taken hold of her and will not let her go.

One branch of the family tree throws up broader questions: what does it mean, here in Aotearoa, to get to forty and discover you have whakapapa Maori, when you have only ever understood yourself as Pakeha? How does this new knowledge reorganise a person’s understanding of herself? How can you go about becoming what you already are?

Ripiro Beach isn’t a perfect book: I grew bored and confused at times by the multiple ancestors, the dramatic set up of opening historic papers started to grow thin, there were far too many epigraphs, and metaphors tended to be painfully on message (a Christmas mince pie is left with a little gap on the topping ‘just in case, later, history wants to seep out of its tidy case.’). But all in all I found myself largely able to forgive any clumsiness because I was drawn in by Barron’s tenacity, honesty and urgency.

The aftermath of a terrible birth, and the damage of her grandparents’ lives read as parallel investigations into the link between being a person who undergoes trauma, and being a person capable of violent rage. The overriding question of the memoir becomes a matter of survival for Barron: why am I like I am?

After the birth of my own first child, I realised that there is a subterranean world of stories which post-partum women whisper and recount to each other. We are careful, secretive, coy with these stories: they are almost never told in front of younger women, no doubt for fear of terrifying them.

I remember feeding my newborn and contemplating the quantum gap between, on the one hand, all the art I had ever consumed about the fog of war, and on the other hand, all the art (almost precisely none) I had consumed about the fog of giving birth. Every imaginable dimension of sex, love and violence are deeply and marvellously probed in our fictions, yet birth and its aftermath remains largely unspoken.

The fact is, there can be injuries to the body and psyche after birth that in 2020 our society blanks out. At the end of the book, having explored the birth experience with a supportive therapist, Barron still doesn’t seem to feel entitled to full-blown anger about this silence. I felt it on her behalf. Do I need to say misogyny?

My search for wellness took years longer than it should have. I believe, after

filling out medical history questionnaires in clinics all over Auckland over six

years, that someone should have connected the dots sooner.

Finally, it’s the beautiful imagery of the placenta that holds the book together. Barron builds a summer home for her family at Ripiro beach, west of Dargaville. This land, which she guesses could be part of the whenua of her iwi, is transubstantiated through te reo into the placenta inside her body, the organ ‘that nourished my babies but nearly killed me.’ The concept of whenua has an accretive weight by the end of the book: melding land, flesh, birth, death, and whakapapa, not as abstractions, but as living forces inside the frame of one woman’s body.

This review was originally published on the Academy of NZ Literature site.