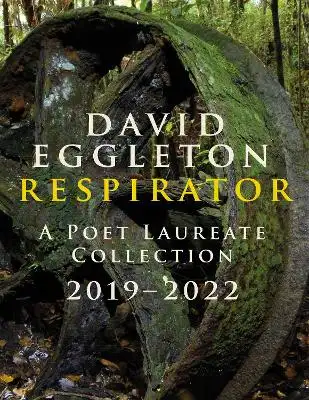

From 2019-2022 David Eggleton was our second Poet Laureate with a Pacific peoples background. His family is Rotuman, Tongan, and Pākeha. He spent some of his childhood in Fiji in the 1950s and 60s. He is also widely known for his performance poetry and tours the country regularly. Like Selina Tusitala Marsh and Courtney Sina Meredith, he is one of those rare poets whose poetry presents vividly on the page and the stage, and in a sense, after Sam Hunt of course, he is a forerunner of the explosion of slam and performance poets who now feature in many festivals and venues here and overseas.

His appointment as laureate was an inspired choice to continue popularising poetry in the community, as Tusitala Marsh so wonderfully achieved. In this review I’d like to talk about the cultural location of Eggleton’s poetics, and how that plays out in this collection.

The title, Respirator, comes from the experiences of the Covid pandemics. Poems are like respirators. They revive, as spoken inhalations and exhalations on repeat, and as written meditations and observations with an emotional core. These small devices take on a life-giving quality in a lockdown. On the Poet Laureate’s blog you can still read the sense of community that comes from the reading of poetry while living in isolation. During the delay to the Matahiwi Marae celebrations, the other poets’ laureate shared their encouraging poetry with Eggleton online, as so many people existed in those months relying on friendship through video calls and meaningful messages. They rightly celebrated his achievement then as the publication of this collection does now.

Written during ‘plague years’, these poems feature all the sass, funk, pop goblin, rock godliness, leather trouser hugging, bookworm shaking, master blasta rants of Eggleton’s signature street poetry ‘hot-foot floogie’ Manukau Mall Walk years. His Dunedin praise poem, ‘The Steepest Street in the World’, is laugh-out-loud funny. His easy referencing of the Waikouaiti water supply problems, his digs at Australia, ‘prime minister after prime minister carried off by dingoes’, his mixing of the serious and the comic, make for a joyful reading experience, one filled with care delivered sonically with more than a chuckle.

Another jouissance of the text is the poet’s mastery of language, and especially technical language from the visual arts, for example using the word ‘grisaille’ to describe Christchurch in monochrome after the quakes in his moving poem ‘Christ the Juggler’. Earlier in that poem the Canterbury earthquakes are personified:

Christ the Juggler dropped bricks, opened trapdoors,

and footnoted the labyrinth by walking it, homeless,

with dry horrors, the shakes, delirium tremens,

the ground leaping from dark sleep as if to hug

those who walk on its surface and drag them under.

The poems are not always easy to analyse in terms of an emotional centre, or sometimes even what they are about entirely due to the cumulative effect of Eggleton’s superlative phrasing. They provide an experience of amplified language where sometimes the stakes are very serious, and sometimes they are more modest in scope and subject matter. The collection as a whole works well, arranged in seven sections. Many of the poems work wonderfully well. I loved ‘Hone’, a tribute to Tuwhare: ‘Poet of the brouhaha, of the feed of oysters’. It achieves its emotional effect without sentimentality.

Eggleton’s poems are centred on language itself, and the verbal pyrotechnics generate an emotional energy that isn’t always dependent on the main subject, but on particularities of each sharp phrase. The anaphoric ‘Steep, steeper, steepest street in the world’ line will ring in my memory for years. In that regard, Eggleton’s hard edged polyvocal, polysemous poems are unique within New Zealand poetry. Eggleton’s voice has brought into our page poetry the energy and dexterity of hip-hop, rap, and the aural qualities of performance.

Like some New Zealand poets who are not Māori, Eggleton deploys Māori motifs, phrases, names, material culture, and art. I am a brother poet who has admired Eggleton right from when I began writing seriously. In part I owe my first book, Jazz Waiata (1990), written in my late teens, to his example as a South Auckland poet who could represent our urban voices.

Since Eggleton is Rotuman and Tongan, many cultural and political issues are related, especially those of neocolonialism. The issue of cultural representation isn’t just his, and probably belongs to a larger conversation about who benefits from the use of mātauranga Māori. Admittedly I am expressing a level of anxiety about the use and activation of mātauranga Māori by non-Māori writers in general, and I feel safe to do so because Eggleton is a brother poet who I respect.

One influential, much loved Pacific poet who preceded David Eggleton and others, Alistair Te Ariki Campbell, did this extensively through his oeuvre, relying heavily on the history of Ngāti Toa Rangatira at Kāpiti. In his case, he arrived in Aotearoa as an orphan from Tongareva. For me, the most powerful resonances in Campbell’s oeuvre are those situated in his Tongarevan heritage.

Campbell’s masterful sequences ‘Soul Traps’ and’Cook Islands Rhapsodies’, and the longue durée of his grief for the loss of both parents resonates for me as strongly as his romantic love poetry. Eggleton’s poem ‘The Navigators’ achieves some of the cultural heavy lifting that Campbell achieved, and owes something to him:

We glided as the frigatebird glides,

to a rising atoll, until the atoll bursts into leaf.

We chanted to Tagaloa, god of the sea,

as Tafola, the whale, breached beside us,

and guided us through the reef,

and then ‘ei reached out to lei

in a green cluster of atolls.

I raise this question of representation because along with some of the work by other poets who are not Māori, the use of our taonga tuku iho suggests representation, and hence the possibility of misrepresentation of Māori world views and beliefs. I make this claim for Māori poets and writers as we are responsible to our whānau and communities and can shape our understanding that way, through discussion with respected members of our whānau, hapū and iwi. This is an open suggestion, wider than the scope of this review, for writers to genuinely interrogate themselves in relation to taonga they are representing.

As an instance of possible misrepresentation, reading the fourth section of Eggleton’s ‘Rāhui: Lockdown Journal’ I felt unsure about the reference to the tupuna mauka as ‘the skull/ of Hine-nui-te-Pō’: Kāi Tahu traditions refer to the mauka as tūpuna and crew members of the Āraiteuru ancestral waka. Furthermore, the stanza begins with a reference to Franz Josef Glacier whose Kāi Tahu name is Ka Roimata o Hine Hukatere, the tears of Hine Hukatere. By swapping one female deity for another, Hine Nui te Pō for the mountaineering ancestor Hine Hukatere, the mythology and the associated geographical mātauranga is altered. The poet may have a different source but none is cited in the acknowledgements.

David Eggleton highlights the importance of whakapapa in his own usage of the Kānaka Maoli (indigenous Hawaiian) term moʻokūʻauhau to finish the penultimate stanza of the richly satisfying poem ‘The Navigators’:

for life is an ocean wave,

from the creation of the world,

from the time of A’a, te atua, the gods,

from the time of kūʻauhau, whakapapa, genealogy.

Māori terms, art, material culture come with responsibilities derived from whakapapa such as manaaki tangata, and mana motuhake. Why use taonga handed down for specific purposes from a different culture?

Over a thousand years ago iwi Māori became separate Moanan peoples with our own traditions and diversities. Whakapapa provides responsible pathways for those who transmit it to the next generations kept warm by many facets of mātauranga including the arts. We can celebrate that, in the same spaces together, if we respectfully remind non-Māori that we are tangata whenua and kaitiaki of our traditions and places in a spirit of friendship.