The title signals the thrust of the narrative. Inge Woolf was born Inge Ponger in 1934 in Vienna. In 1938, after the Anschluss (German occupation of Austria), she and her parents fled to England, via Berlin, to escape the virulent anti-Semitism of both the Nazi regime and many fellow Austrians. A large number of their relatives were not so lucky and were murdered.

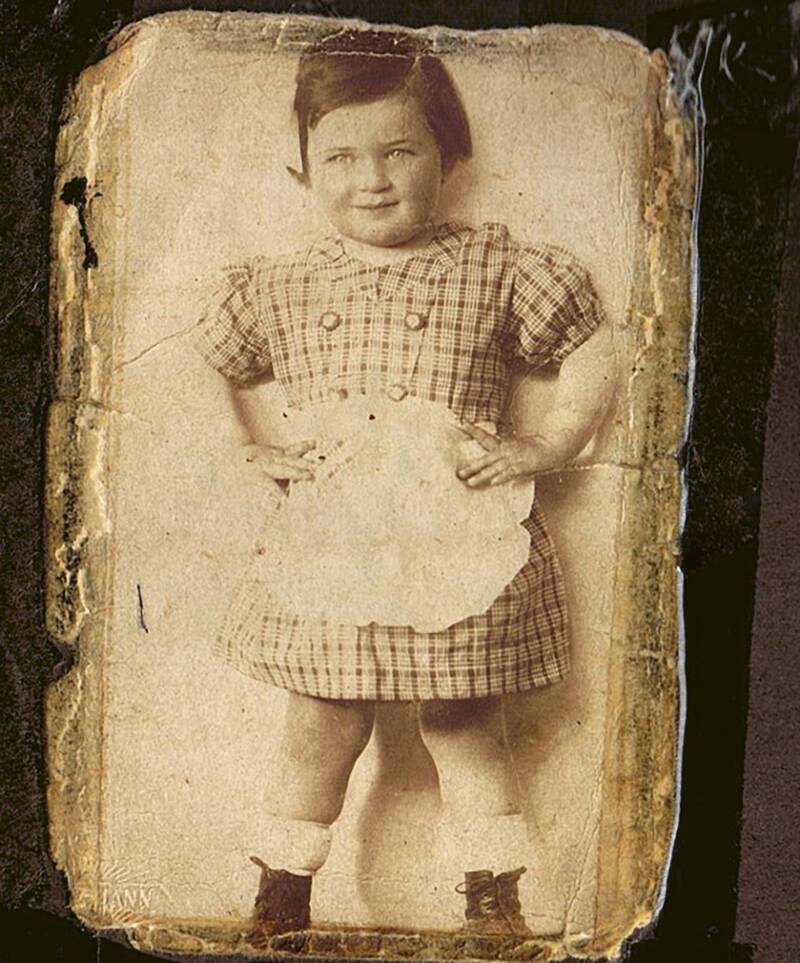

The picture of Inge that her father carried with him during the war, taken in Vienna c 1938.

Inge did not learn that she was Jewish until after the war ended. Out of necessary caution she’d been baptised and ‘passed’ as Christian. Her father served in the war, which contributed to his early death. In 1957 Inge and her mother migrated to New Zealand, to join her maternal uncles and reconstitute their family, as much as possible. She lived at first in Auckland, where she married photographer Ronald Woolf in 1959, and then in Wellington. They had two children, Deborah and Simon. Tragedy struck again in 1987, when Ronald, now one of the country’s leading photo-practitioners, was killed in a helicopter accident.

It seemed that their commercial photography business – bought from the eminent photographer Spencer Digby in 1961 – might be closed, but Inge had considerable organisational skills and business acumen. Simon became the principal photographer, with Inge integral to management, as well as doing some photography herself. Her drive and ability to adapt quickly, organise effectively and cooperate with others extended to a range of activities that benefited the broader community – for example, in Zonta, a national women’s organisation.

Inge and Ron, Wellington c 1973.

All these qualities came to the fore after the 2004 desecration of Jewish graves, including Ronald’s, at Makara Cemetery. That triggered the creation of what became the Holocaust Centre of New Zealand, of which Inge was the founding director. The Centre’s purposes are commemorative, educational and conscious-raising in combating anti-Semitism and racism generally. It has made a big impact, as did Inge’s work for the Centre as long as she was able. Honours came her way, though one senses from her memoir that others, family and community always came first, and that she valued practical down-to-earth work more than self-pity. That is her legacy. Whether or not she was conscious of it, Inge Woolf’s work embodies a fundamental Judaic principle and value, tikkun olam – ‘repairing of the world’.

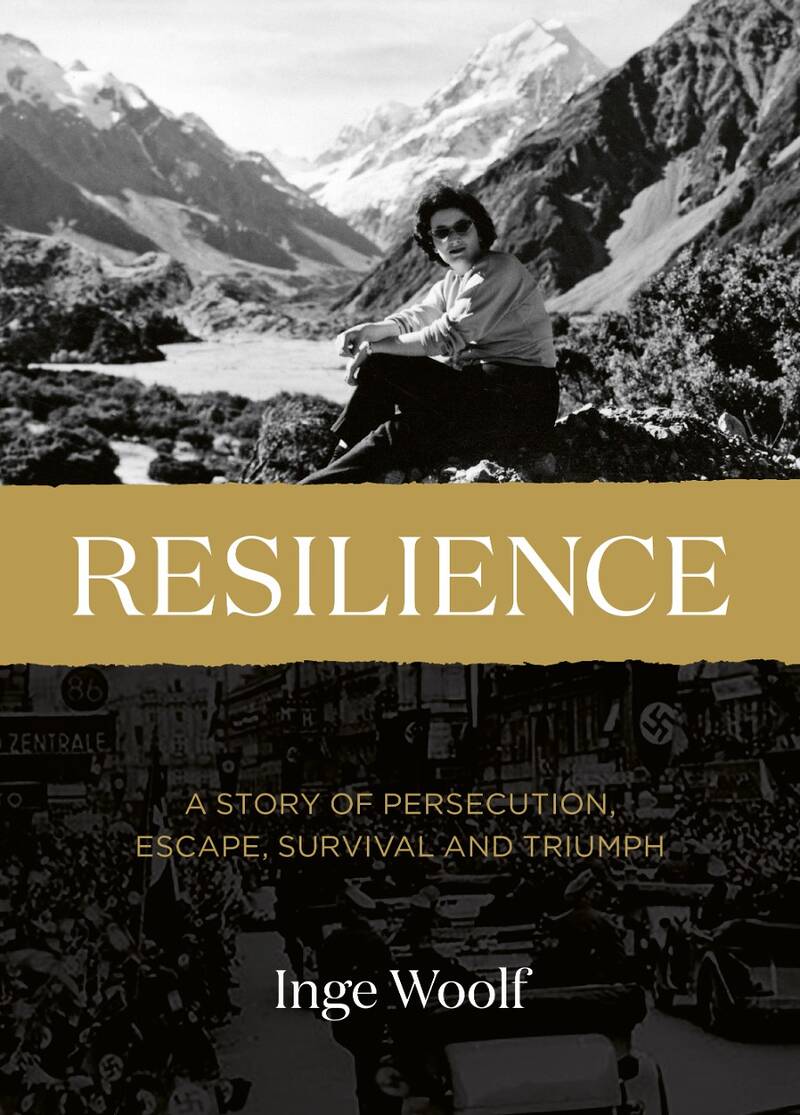

At the time of her death in 2021, Inge’s memoir existed predominantly in note and draft form, so this book was completed by her daughter, Deborah Hart. That is never an easy task. How do you complete another’s manuscript and retain their voice? To this reader, though, a distinctive voice resonates clearly: direct, matter-of-fact, unadorned and ‘unsophisticated’, in that it is not the voice of a professional writer, but of a plain-speaking ‘straight shooter’. The articulation of the narrative is simple, but not simplistic. What we read is compelling and Inge’s story is enhanced by the many photographs judiciously placed in relation to the text. They include photographs from Austria in the 1930s, England and Scotland and then New Zealand, many of them Ronald’s and Simon’s. One of Ronald’s features on the cover, of Inge Woolf on honeymoon, looking directly back at her husband and now us, Mount Cook behind her. That mountainous landscape inevitably brings to mind the Alps of Austria, from whence she came; a homeland lost, another found.

Design-wise Resilience looks good. It also has succinct supplementary materials: an epilogue by Deborah Hart, followed by family recipes; a family tree (like so many of those of 20th century European Jews, marked by multiple deaths during World War II); a Holocaust and New Zealand timeline, and an historical background on the ‘rise’ of Nazism, its conquest of much of Europe, war and its aftermath by Giacomo Lichtner, an historian at Te Herenga Waka/ Victoria University.

Resilience is an A-Z of a life, straightforward, unembellished, comprised mostly of facts and Inge’s views. It is an exemplary narrative too, in the sense that Inge Woolf’s life can also represent many other lives of her generation of European Jews and their experiences of persecution, displacement, migration and various kinds of ‘homecoming’ – new lives in new lands, pasts revisited, usually many years later, when that became feasible. Typically such memoirs and biographies came a generation after displacement and the War, from the late 1970s–early 1980s onwards.

As such Resilience belongs to a global genre, notable examples of which include Helen Epstein’s Children of the Holocaust: Conversations with Sons and Daughters of Survivors (1979) and Where my Mother Came From: A Daughter’s Search for Her Mother’s History (1997) and, in New Zealand, Sarah Gaitanos’s The Violinist: Clare Galambos-Winter – The Holocaust (2011) and Diana Wichtel’s Driving to Treblinka: A Long Search for a Lost Father (2017).

With some notable exceptions, few such experiences of anti-Semitic persecution, escape, survival and migration from a personal perspective were published earlier. Why? People need time to accommodate gruelling and traumatic experiences and, first, escapees and survivors needed to re-establish lives, find work, repair themselves as much as possible, raise families. Sadly, some were unable to do this, with trans-generational consequences, as addressed in memoirs like Wichtel’s. Resilience shows that in order to survive and make a new life you just had to keep going, however tough that going could be. As Samuel Beckett – a member of the French Resistance during World War II – wrote in The Unnamable (1953): ‘You must go on, I can’t go on, I’ll go on’.

At the start of the book the question is asked: what relevance has this story today? A lot, so it turns out. Firstly, it is a memorialisation. One of Nazism’s goals was to eliminate Jews not just in the present and future, but also from the past, as if they had never existed. Resilience is a memory book, recalling lives lost and lived, providing familial and collective Jewish continuity. Secondly, Resilience is urgently topical now in relation to the unfortunate resurgence of anti-Semitism globally – whether explicit, implicit or coded – and the employment of age-old tropes, such as alleged Jewish control of money and media.

Sometimes the ‘oldest hatred’ is overlooked here – for instance, Towards a Grammar of Race (BWB 2022) on racism in New Zealand does not include an essay on anti-Semitism, or even a reference to it, as far as I could see – a peculiar absence, given that the term ‘racism’ (originating from the French racisme) entered common usage in the mid-1930s in relation to Nazi persecution of Jews. This country has been far from free of that blight, both in the past and present: the Makara desecrations were not a one-off incident.

The very conditions that led to the experiences of Inge Woolf and her extended family make Resilience a necessary book for today. The Irish historian Conor Cruise O’Brien observed: ‘Anti-Semitism is a light sleeper’. We forget that at our peril.

Inge Woolf and Deborah Hart. Photo: John Walton.