A month after she won the Jann Medlicott Acorn Prize for Fiction at the 2023 Ockham New Zealand Book Awards for The Axeman’s Carnival, Catherine Chidgey is back with her eighth novel, Pet.

A slow-burning sense of menace and unease simmers beneath the surface of this stylish psychodrama set in a Catholic primary school in the 1980s. A motherless twelve-year-old girl’s crush on a charismatic new lay teacher and her yearning to become her pet fuel a richly layered tale of deception and misplaced trust.

The opening chapter introduces forty-two-year-old first-person narrator Justine in the novel’s present day setting of 2014. She is visiting her father at his rest home with her twelve-year-old daughter Emma, whom her father confuses with Justine while mistaking his actual daughter for his late wife. But it is his caregiver Sonia who Justine can’t take her eyes off: she bears an uncanny resemblance to Mrs Price, her teacher thirty years earlier.

Then we’re swept back to 1984 when Justine herself, like her daughter, was just twelve years old. Looking back with the wisdom of hindsight, she relays the story of the events that took place in a tumultuous year of her childhood at a Wellington convent school – Catholic-lite – one staffed predominantly by lay teachers. The nuns are largely off-stage, except for the compassionate and observant Sister Bronislava.

Justine is an only child. Her mother has recently died and the household is melancholy and dysfunctional. ‘Up in the spotless house, curtains drawn, my father listened to his sad records and drank his sad drinks.’ And then, surprising the reader as much as Justine – a sudden seizure, ‘thundering through the hot air, knocking me to the ground’. This tendency to seizures will turn out to play a role in the story.

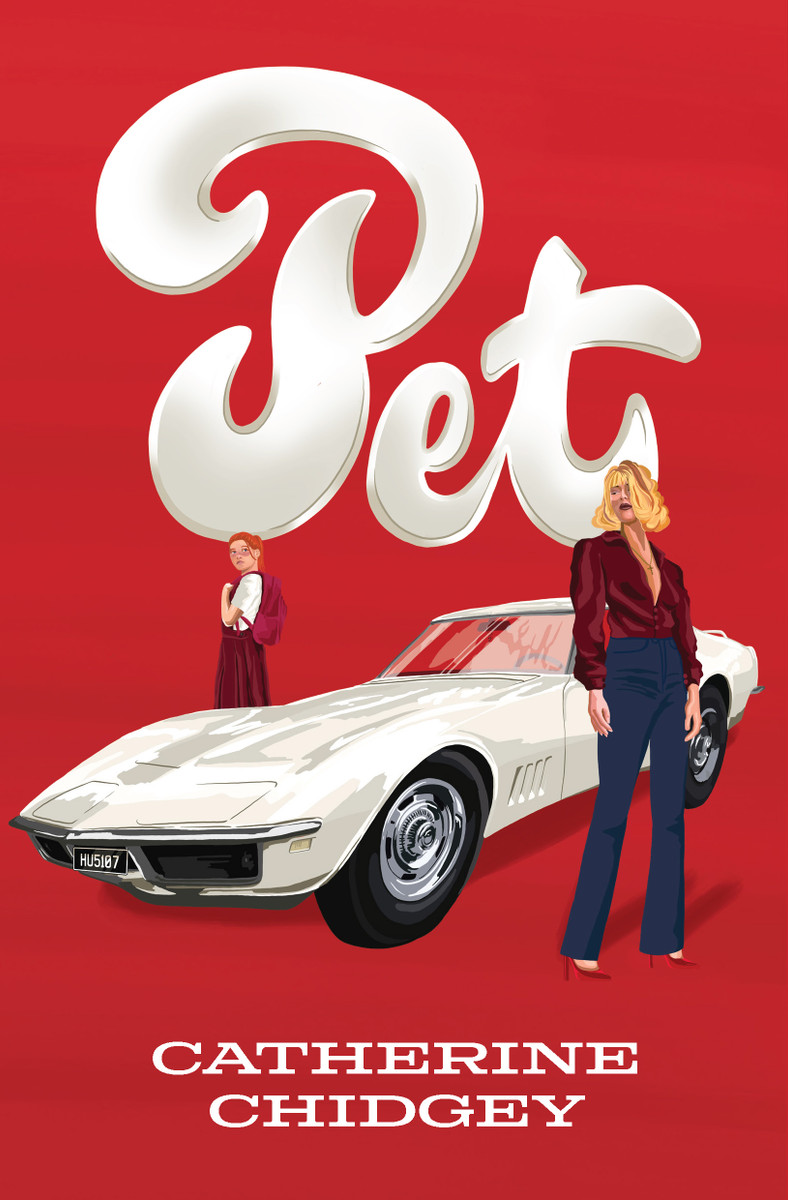

The setting is ripe for the arrival of a disruptive presence who will fill an absence in the life of this vulnerable, bereaved girl. So enters Justine’s glamorous widowed teacher Mrs Price. She drives a sporty ‘white Corvette with the steering wheel on the wrong side, the American side . . . Glass bangles clicked at her wrists, and she wore her wavy blond hair with a deep fringe like Rebecca de Mornay.’ She presides over a classroom in which ‘the Virgin Mary gazed out from her picture frame, her heart full of roses and fire’.

Justine and her classmates are pushovers. Soon they’re all in helpless thrall to their charismatic teacher, competing for her attention, hanging off every word, living for the smile ‘spilling across Mrs Price’s beautiful face . . . We would have done anything for her.’

By addressing her pupils as ‘People’ instead of ‘Children’, Mrs Price makes them feel responsible, more mature, binding them closer to her. But the fickle and duplicitous Mrs Price plays the children off against each other, her selected pets falling in and out of favour in an unwinnable game of snakes and ladders. Wannabe pets are hungry to be ‘seen’ by Mrs Price. To feel anointed. Elevated in status. Envied. Special.

There were three or four of them at any one time, usually the pretty girls, the handsome boys, who already had lots of friends and didn’t need extra success. Sometimes, though, she’d choose an unpopular child – and straight away, that child’s luck started to change.

After discovering that Justine’s poor performance in class has been impacted by a seizure, Mrs Price addresses Justine as ‘Darling’ and ‘Sweetheart’. Her attention makes Justine ‘feel tingles in the back of my neck and all across my scalp’.

Justine achieves the ultimate goal. Everyone knows she’s become ‘the favourite of the favourites, the top pet’. She cleans her teacher’s house and runs her errands, even collecting her chemist prescriptions: opioids, like morphine sulphate.

The convent background is sketched in with a few deft strokes. The nuns’ section, a series of dark, wood-panelled rooms and ‘statues of Mary and Jesus standing about as if waiting to be offered a seat. . . Over in the corner, by the piano, a harp jutted into the empty space like the prow of a ship’.

Chidgey possesses a sensitive eye and ear for the tone and feel of the intense hothouse of girlish friendships. The petty squabbles and jealousies that flare up and quickly fade. The competitiveness. The comparisons. The cruelty and judgments. At twelve, Justine and her friends are already assimilating messages about dieting, the ideal body shape – thin.

At lunchtimes the girls sunbathe, draping themselves over the stormwater pipes, ‘their long hair rippling down on the hot concrete flank’. Justine and her best friend Amy Fong eat their lunches inside the pipe. While sharing a bath during a sleepover, Justine and Amy rank their female classmates from prettiest to ugliest, picking out their faults: ‘a big behind, hairy arms, fat earlobes, a crooked tooth . . . Mostly we ranked each other fourth and fourth was believable; fourth was fair.’

Casual racism and misogyny are threaded through the story, festering away in the background, often not explicitly recognised by Justine other than by feelings of discomfort that she cannot articulate. Cherished possessions belonging to Justine and her classmates go missing, and Amy is scapegoated because she’s Chinese, the target of suspicion and class racism. Classmates taunt Amy about her parents, who run the local fruit and vegetable shop, telling her they give wrong change and ‘shove the rotten fruit to the bottom of the bag’. One boy pulls his eyes into slit shapes and mocks Amy’s parents’ accents. Justine, her supposed best friend, now more of a frenemy, makes no attempt to defend her.

When the classroom thefts escalate, Amy again becomes the target.

Dirty thief, our classmates call in her wake. Liar. I wish you were dead. Why don’t you kill yourself? Mrs Price heard them but never intervened. I didn’t know what to think; I just knew I had to be careful.

The power imbalance and the subtle coercion and deception being practised by Mrs Price become evident: the gradual accretion of liberties taken, of inappropriate invitations and actions, obscure to the children – until they aren’t.

Mrs Price has been elevated onto a pedestal by everyone. But whoever is raised must inevitably fall from grace. Even the biddable Justine proves dispensable when she loses her coveted pet status. Cracks appear in her beloved teacher’s façade. Justine becomes disillusioned and suspicious. Doubts niggle when she makes an unexpected discovery on an outing with Mrs Price. Doubts that escalate after Amy reports that she spied their teacher shoplift a packet of tea from her parents’ shop. Mrs Price’s method of publicly outing the falsely accused thief is cruel and reprehensible.

As the story progresses, we become gradually aware that we’re being told a story by an unreliable narrator, contributing to the feeling of unease. The ground shifts as the story progresses, truth and reality treading a slippery path.

This is a captivating and often unsettling read. Pet is that rare local phenomenon – a literary novel with not only nuanced characterisation, vivid descriptions, pitch-perfect dialogue and artful language but also a dramatic story with a propulsive narrative momentum. Things happen, keep happening. Complications. Unexpected twists and turns. Murder. The denouement is as unexpected as it is dramatic. No spoilers.