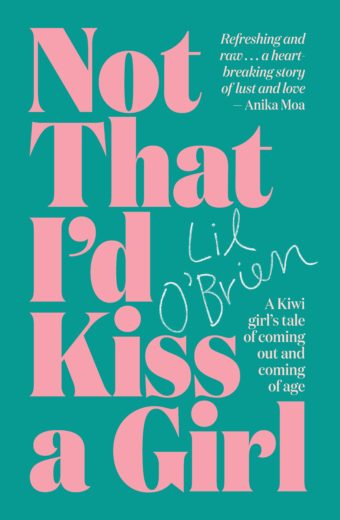

Lil O’Brien’s memoir Not That I’d Kiss a Girl is billed as a ‘coming out and coming of age’ tale, yet it begins in the aftermath of a moment that feels less like coming out and more like being pushed: Lil’s parents overhear her, nineteen years old, saying she likes girls. They don’t take it well. It forms a rupture in her life, a split: before they knew, and after. She loses her family, and she’s told it’s her fault.

Lil doesn’t begin as the cliché: a shy, insecure girl-in-the-closet. From the start she is full and nuanced on the page. She spends a lot of time judging others, instead of the other way around. She judges the ‘First Ladies’ at her school, after becoming friends with them. She judges the women in her Otago University coming out group ‘Blossom’ (‘I felt much better about myself after meeting the others’). Even when she’s the most conflicted about her sexuality, she still has an innate confidence, an easy way of moving through the world.

O’Brien acknowledges this privilege, though sometimes this acknowledgement comes too late. Only after her parents kick her out, almost halfway through the memoir, does she explain that they paid her rent, her uni fees, and a weekly allowance for bills and food. She was armed with a taxi card, a petrol card, and a credit card, all courtesy of her father. (We learn, chapters later, of the Farmers charge card when she tries to buy undies.) Reading this, I was taken aback. As someone who’d never even heard of a petrol card, this felt like need-to-know information.

But nothing is withheld on purpose. More than anything, this is a very honest book. O’Brien describes things many people never would. The fatphobia she inherited from her parents, leading on a seventeen-year-old, judging a girlfriend for her white boots. Being bad at sex; passing out during sex; crying, often, mid-sex.

Everyone knows a Lil – gay, but somehow almost always attracted to straight women. She raised my bisexual heckles once when she lumped two women together: ‘my currency value was weak compared with men’s when it came to Kasey and Lacey’. Lacey is a bar-sexual, leading Lil on for the attention of men, but Kasey, who identifies as bi, just isn’t that interested in Lil, and ends up kissing her male flatmate.

It is hard to tell whether the intended audience is local or international. She explains where Dunedin is, and that New Zealand doesn’t have a tipping culture, but then describes the bottom of someone’s denim shorts as ‘daggy’.

Where O’Brien’s writing excels is in capturing the elusive, naming the unnameable: the intensity of young love, imperceptible shifts in power, what remains of memories which have been lost to shock: ‘What happened next survived in my memory as a series of sensory elements and emotions. It’s as though my brain has tried to block out the detail but hasn’t protected me from the feelings: dread, terror, nausea. It’s easy to bring back the ghosts of that memory, even today, sixteen years later. I remember the soft night-time lighting of the room and the TV murmuring in the background. I remember the shape of what they said.’ She describes friendships where the conversation doesn’t flow as ‘like a headwind: you have to lean in a little harder to keep your balance’ and the memory of a kiss as ‘never enough, like an image you put through the photocopier twenty times until it’s blurry and indistinct.’

The act of ‘coming out’, as a singular big event, is (I hope) one that’s becoming less and less necessary. So the memoir’s central focus – on this alienating and confusing process – timestamps the story as much as the ‘hologram orange’ ball dresses, the all-caps all-contractions text speak and Nelly’s ‘Ride wit Me’. And, as you would hope, the early 2000s gay content is all there: message boards with online lovers, Tumblr feeds of kissing girls, The L Word. Lil attempts to download the first episode with her Dunedin flat’s 56kbps dial-up: ‘After a week of stops and starts and the agony of waiting, I had just over a minute and a half’. ‘Outstanding’, she calls it, this minute and a half of Bette and Tina in their pyjamas getting ready for work. ‘Neither of them looked like they were going to be killed off or go back to men.’ (Maybe this joke is intentional, or maybe O’Brien never made it to Season Three, because Tina does exactly that.)

‘Not That I’d Kiss a Girl’ is truly, deeply, hilarious. Lil dismisses the one out girl in her uni hall when she hears ‘that she’d bragged about having a double dildo. What an attention-seeker, I’d thought. Even though I couldn’t stop wondering what a double dildo was’. The humour is self-deprecating, open, and necessary. There’s a lot of pain in this memoir. But even in the darkest places, O’Brien still manages to find the light.

O’Brien spent two years sharing this story in high schools as part of Rainbow Youth’s education programme, and this shows. It reads, at times, like how you’d tell this story to a friend. A chattiness seeps in the edges: ‘We’d talked about gay stuff and lesbians and just, like… gay stuff!’ There are colloquial turns of phrase, which feel tired and overused. Floodgates open, white knights appear, weights are lifted, stomachs twist in knots, and drop. There are kicks up bums, lovers gathered in arms, turning points marked. Her friend Jack is described (twice) as ‘the son [her parents] never had’. People get their acts together, or don’t. Lil does a lot of standing on her ‘own two feet’.

O’Brien is repetitive, too, in documenting her inner monologue. She tells us again and again how, at first, she couldn’t even think about her sexuality, then she couldn’t name it, then she couldn’t ‘confront it head on’. She reiterates, right up until the end, that her family finding out so early ‘hadn’t been part of the plan’. This kind of metanarrative felt, in most places, unnecessary. She tends to overexplain the significance of events. For example, she describes the electricity between herself and her high school not-girlfriend, then she describes feeling absolutely nothing with her university not-boyfriend, and then she says, ‘The two experiences couldn’t have been more different.’ She even reintroduces characters who need no introduction (Harry, her first boyfriend, and Bridget, her ex-best friend.) O’Brien needs to trust her story – and her reader – and let go of our hands. I got the sense that this stemmed from a need to be understood. Similarly, I felt a need to ‘get everything out’, to make a record of what happened, that at times meant the cataloguing of unnecessary events and exes.

But you can see why O’Brien might feel this way. Hers is an important story to tell. It spans the cultural shift that has taken place in the last couple decades, at least in Aotearoa, where it has become much less socially acceptable to be homophobic. Lil experiences that unsettling phenomenon, where people who once judged her now want to act as though everything is fine. She asks, ‘how do you get closure when the main perpetrator has never acknowledged what happened? How do you close the door on something that – in their eyes – never occurred?’

This book seems like a pretty good start.

This review was originally published on the Academy of NZ Literature site.