Once, on a poets’ tour of Ireland, I opened a novel that happened to be lying on the table. I had been surrounded by Irish voices for perhaps a week and as I read the pages, Anne Enright’s story came alive with a full-blown Irish lilt. Even within my head, it was an immersive auditory experience.

For a somewhat similar reason, although you can read and deeply appreciate Mohamed Hassan’s poetry exclusively from the page, I suggest you find his poetry performances online and, if possible, take the opportunity to see him live. (He won the 2013 Rising Voices Youth Poetry Slam and the 2015 NZ National Poetry Slam; his performances are compelling.) Then when you read this collection, the words will come alive with his actual voice; you will see his face and recognise this fellow New Zealander, who is speaking to you.

And speak, he does.

Hassan is known for his journalism. His 2016 podcast series, Public Enemy, about the rise of Islamophobia in the US, Australia and Aotearoa post-9/11, won Gold at the 2017 New York Festival Radio Awards and his 2020 Radio NZ/Middle East Eye podcast series, The Guest House, explored the aftermath of the Christchurch mosque attacks.

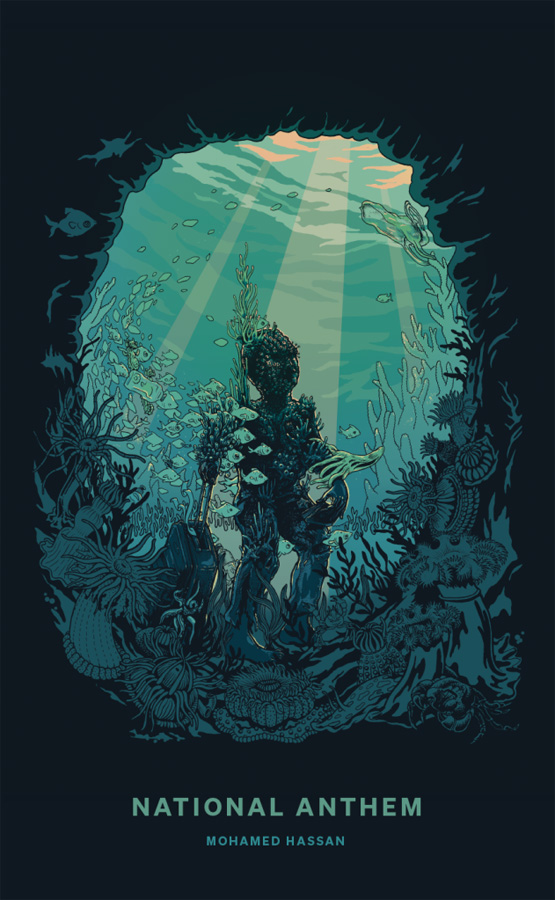

Now National Anthem has been shortlisted for the Mary and Peter Biggs Poetry Award at this year’s Ockham New Zealand Book Awards. The collection explores similar themes to the podcasts: community, migration, refugees and diaspora, transcultural identity, conflict, nationalism, racism and white supremacy, border control, Islam, the Mosque attacks, anger, loss and grief, mental health, and the search for belonging, peace, home.

Yet poetry is set apart from journalism by its particular musicality and rhythms, its ability in so few words, through stark beauty and intimacy, to seduce and ambush with the whole gamut of human emotions and experience.

In ‘When they ask you where you are (really) from’, Hassan writes:

Tell them

you are

…

a whisper

or a window

to what your country

could be

if only

it opened its arms

and took you

whole

This is the first poem of the collection. Where do we hide our faces after that?

National Anthem has four sections and the titles of the first poems in each of the sections either begin with ‘When they ask you…’ or ‘When they tell you…’ They are familiar interactions for anyone with a non-white ‘migrant’ background, whether we arrived last year or decades ago as a child, whether our families have lived in Aotearoa for generations.

Where are you (really) from? with the emphasis on the really, which may or may not have been explicitly spoken. Go back to —– or Go back to where you came from often with expletives. Why do you speak (English) so well? These suggest the precariousness of belonging for those of us who look or sound or have customs different from what is considered normative. But in the final section of the book, the title of the first poem is new and probably only addressed to Muslim New Zealanders: ‘When they tell you they are sorry’. Its end is shocking.

In the poem, ‘Bury me’, Hassan describes loss that ‘lives with you, sleeps in the spare room/by the laundry and occasionally eats your food’. In ‘John Lennon’, he says, ‘I am sweating/guilt a homeland I have/sewn onto my palms/but can’t dream in hold/my Arabic between/my knees’. He says, ‘my mother taught me//Allah blesses every failure’ …. ‘I unbutton English grammar/but daydream of not having/a tumoured tongue/tumbling over the weight/of expectation’ …. ‘it shouldn’t hurt this much/to love a country that does/not love you back//that no longer has a place for you’.

In the poem, ‘It’s been 48 hours since I last saw a white person’, Hassan finds himself in Istanbul where he cannot speak the language, ‘where you can still smell the shrapnel and trauma’ and realises no one has asked him where he is from, ‘and when they did it was warm/and kind and not distant and not waiting//for a chance to snap and not watching me/from the corner of their eye…. and for a second I feel safe/like a home or a book you can see yourself/inside of’.

‘And before that we were stars’ tells the story of refugee lovers trying to find their way to be together: ‘we’ve been stretching words like this/four years making bridges out of paper/folded like passports/like sailboats/floating into the sky/have you ever tried to fold/your heart into an envelope?’

Sometimes Hassan’s poems are a quiet heartbreak; sometimes they are a loaded gun. There are hard-hitting poems such as ‘White supremacy is a song we all know the words to but never sing out loud’, those with the brutal clarity of ‘Aotearoa Inc’. There are poems of warm, defiant gentleness like ‘The guest house,’ which pays homage to the Al Noor and Linwood Mosques.

Yet in the darkness there is also humour. ‘Office Christmas party’ begins:

All my life I’ve wanted to fit in and never have

like a hippopotamus at an office Christmas party

who doesn’t drink for religious reasons

no one knows what to do with me

small talk feels like root canal

I am bored by my own existence

I laughed at the beginning of ‘The mother of the world’:

Only Arabs would care so much about appearances

they’d have a second lounge with plastic wrapping

you’d get a smack if you sat on it without permission

God help you if you spilt food

Plastic-wrapped furniture is number 26 in the old online list 102 Ways That You Know You’re Chinese. I remember visiting another Chinese family and having a cup of tea on a plastic-wrapped sofa. My Pākehā husband tells me his grandfather and many others in 1950s and 1960s New Zealand also had plastic-wrapped sofas, a post-war strategy to preserve the good furniture. In the particulars of this scene – the dynamics between elders and children, even the furniture – we find our common humanity.

In his Radio NZ interview with Kim Hill last year, Hassan said that his identity precedes him wherever he goes. The Christchurch Mosque attacks taught him that if he is going to be visible anyway, he may as well be visible on his own terms. He said belonging is an act of resistance, a verb.

In the last poem of this collection, ‘(un)Learning my name’, which Hassan also performs online, he describes the way his first white teacher kept correcting the pronunciation of his name in front of the class:

until I learnt how to stumble

/ over

/ my identity

/ the way

/ she did

It took nineteen years to be able to say his name publicly again the way his mother did when she named him. The poem has struck a chord. In October last year this poem had already hit one million views on Twitter. Like so many poems in this collection, readers/listeners/audiences either recognise something of their own experience or they learn from his specificity. Teachers now reconsider how they interact with their students. As he speaks his own name, the poem ends:

it feels like I have

/stolen

something back.

This collection is part of a challenging conversation. These poems are not the last word. I look forward to the next collection where Hassan takes us further along on his journey. But here, now, he suggests possibilities for a new kind of national anthem. He steals something back for himself and his community. He steals something back for all of us.

This review was originally published on the Academy of NZ Literature site.