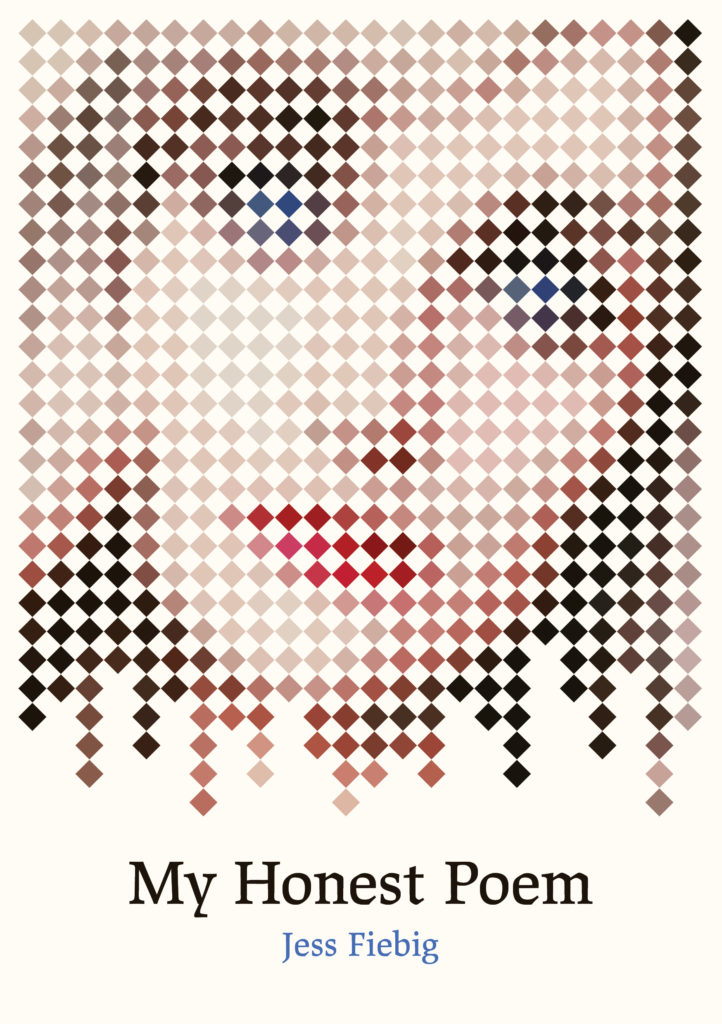

In Jess Fiebig’s debut collection, My Honest Poem, there isn’t much intention to surprise. ‘Duck Hunting’ is about duck hunting, ‘Saturdays at Bailey’s Irish Bar’ describes the speaker’s childhood Saturdays spent with her stepdad at Bailey’s Irish Bar, and ‘Moving In’ does, indeed, describe the process of moving in somewhere. The titles are largely prosaic and plainly descriptive. There is rarely any trick played, any swerve or bait-and-switch. The collection’s overarching structure generally orders the poems based on their apparent chronology, with section titles giving hints as to the trajectory of the poet’s journey through adolescence, relationship making and breaking, family and domestic violence, mental illness, and bodily harm, both accidental and intentional.

There’s obviously a huge tangle here of trauma and self-discovery, and the simplest way to work through it in book form is the road chosen – from start to finish, or close enough. Yet, despite My Honest Poem’s structural straightforwardness, there is no shortage of spontaneous delight in the language of Fiebig’s lines and the playing her poetry can do. In ‘Fawns and Foals’, ‘your crop-top, messy topknot/mixer in hand’ sparks with assonance and sibilance, and the ‘yolk-yellow fennel flowers’ of ‘For Kelly’ is a fluttering tongue twister. Some pieces have rhyme schemes, and some riff on the hypothetical. One particularly moving exercise in the imagined is ‘Mickel’, whose speaker describes a girl who died in their shared youth as having grown up, fallen in love, and had a child. Fiebig’s poetry, at its best, stretches to surround both the known life and the life only hoped for. When they are placed alongside one another, a reader feels both heartbreak and joy – and more of each for the space between.

Fiebig is also preoccupied with the image and the action of the mouth. So many of the poems in this collection are made of breath and tongue and kissing; there’s ‘breath growing thick and sour/in the night’, there’s ‘the honeyed whisky/of your tongue’, and there’s an invitation from the speaker to ‘kiss/the dark sweetness/fermenting inside me’. The mouth is almost the primary mode of action for many of the characters in this collection – the limb of choice. It’s a vessel of the lovely and the acrid; a tool for kissing and for purging.

The pacing of spoken word, a form Fiebig, a performer, is used to working with, finds its way into the collection’s briefest lines. Some are only one or two syllables long and move in the mouth of the reader like tiny hammers: ‘your kisses/so gentle/on my/eyelids’. The spokenness of the collection is also inherent in the way each sentence becomes the next, often unpunctuated, as if the whole page is a melisma. ‘Shinjuku’ is one particularly liquid poem, in which the speaker becomes the moth ‘tapping on the kitchen window’ before returning to human form ‘to cup the bowl/of dark green matcha with both hands’. It’s in poems like this and ‘As We Stand Back on Sumner Beach’ that Fiebig zooms in and out to flit, without bombast, between cliff and kitchen floor.

Perhaps some of these poems should end sooner. Some final lines work too hard saying what may have already been clear two stanzas earlier, or do more to wind down than to build up. But while this habit might mean a poem loses some of its pacing and freshness, it also serves to remind me that Fiebig’s priority is to, as faithfully as possible, honour the feeling that forms each poem’s budding heart. Why else call your collection My Honest Poem? Of course, poems cannot be feelings only – and Fiebig knows this, too. It seems quite dull to describe a book of poetry as having a thesis, but I am going to, and this poet has written it for me:

This is poetry,

to feel emotions like hot iron

pressing on my skin,

burning to describe the most

complex parts of myself

as simply as I can […]

(From ‘This is Poetry’)

So My Honest Poem may be more transparent than opaque, but not by accident. In fact, the most satisfying moments of this collection for me, a self-involved poet, are those in which the poem recognises itself. In ‘Twenty-Seventh Christmas’, the speaker’s chronicle – ‘wrote a list/pretended the list was a poem/wished I had something/more profound to say/than this’ – rounds out a laconic account of a holiday spent sleeping, alone with a dog, thinking about suicide. Similarly, ‘Cry, Babe’ features a metatextual exchange that invites the reader into the poem as it’s being written: ‘I say I’m going to write a poem/about her writing a poem/about the godwits;/she tells me that’s been done’.

Fiebig does not play this self-referential move often enough for it to become a gimmick. Instead, these brief, plain moments allow this collection to join the thousands-year-long conversation from poet to poet, in which we’re all trying to decide how best to say what seems unsayable, and how to write about kissing. My Honest Poem is a lucid, uneasy, and tender telling of a life so far, bravely open, untricksy, ready to be shared.

This review was originally published on the Academy of NZ Literature site.