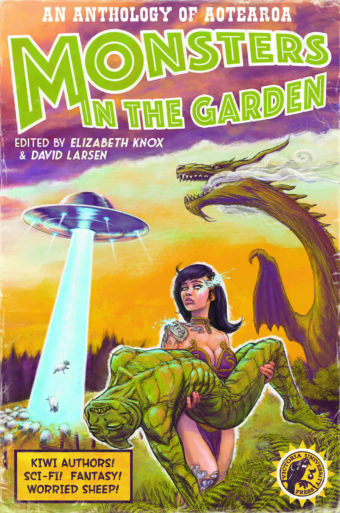

Victoria University Press’ Monsters in the Garden: An Anthology of Aotearoa New Zealand Science Fiction and Fantasy, edited by David Larsen and Elizabeth Knox, is escapism for times of trauma – a speculative anthology for a weird year.

‘Speculative fiction’ is an umbrella term encompassing many genres and subgenres, including fantasy, science fiction, dystopia, horror, magic realism, surrealism, slipstream, gothic, and new weird. Most of the stories in Monsters in the Garden are pure magic, exploring existentialism and escapism as only speculative writing can.

I wish I had room to unpack the beauty in these stories fully. Many delve into the necessity for escapism amidst trauma. For example, Emma Martin’s ‘In the Forest with Ludmila’ shows a snippet of the lives of two sisters. The pair live with a violently drunk mother and neglectful grandmother. The sisters wait every night, with bated breath, for the clock to strike twelve. That is when their forest appears. Juliet Marillier’s ‘By Bonelight’ is a gentle fairy tale in which a child’s evil stepmother sends her out in a blackout to fetch light. The child is scared, but carries her homemade doll, whose whispering words chase away fears. Early on is the first two chapters of Maurice Gee’s ‘The Halfmen of O’. This is the reading equivalent of slipping into a freshly made bed, such is the comfort of Gee’s prose.

An extract from Margaret Mahy’s unpublished novel Misrule in Diamond is enchanting. When we were children, we needed this novel. How sad that we never got to build a house devoted to Diamond in our imaginations; a place to retreat when growing up got too hard. Mahy’s manuscript is full of clowns, assassins, mad princes, and towers of crumbling stairs. Once Mahy completed the eight-hundred page fantasy, Knox outlines that Mahy was, ‘… discouraged by several readers, wondering what kind of beast it was, whether this was her audience, or the best use of her time.’ This seems like the equivalent of turning down Philip Pullman’s Northern Lights. The world needs these kinds of stories, places for people to pour their dreams. It is gratifying that what was left of Mahy’s unpublished novel finally has a home.

Stories of existential exploration are numerous. To my mind, this is the great strength of speculative fiction. Sometimes the only way to communicate complexities is to place them in a pot of strangeness, where they warp, and produce something that is somehow more honest than reality.

Pip Adam’s short satire ‘A Problem’ made me laugh and cry at the familiarity of its absurdity. All the important men in the world seek to solve the problem of women being raped and killed, settling on the solution of building robots that men can get all their raping and killing out on. You can imagine how well this turns out.

Some stories subtly address the complexities of this moment in history. Kristen McDougall’s ‘A Visitation’ is set in a world where the Internet suddenly disappears, altering society in weird ways, much as COVID-19 has altered ours. The mother in this tale describes her son acting out his grief on the playground: ‘… resourceful children had taken to using chalk on the quad to draw a giant Minecraft landscape until some kids beat each other up over the direction in which a tunnel should go and the teachers had to ban tunnels.’ McDougall includes many original elements on the theme of loss.

Lawrence Patchett’s ‘The Tenth Meet’ is a sad yet necessary piece on confronting family illness. Harky’s father, Mackie, is so close to death that he has regressed to unintelligible shouts and blubbering. In desperation, Harky’s mother performs a ritual for sick babies that feels like old family magic. Harky must play parent to his father for the ritual to work. He can’t carry his dad, so they pile Mackie into a wheelbarrow; he’s swaddled in blankets and given a sippy cup. Harky then pushes his father from farm to farm in search of support. Patchett explores how communities can pull together in times of trouble, and the difficulties that arise when there is bad blood between neighbours.

But for all its greatness, I feel I must reflect on something that has been gnawing at me – some discomfort in how this anthology is framed. Monsters in the Garden opens with introductions from editors Larsen and Knox. In his, Larsen makes the claim that within these six-hundred pages readers will find a ‘comprehensive selection of the most enjoyable and interesting speculative English-language fiction New Zealanders have written’. Both editors wanted to include additional work as well. This, of course, is the peculiar challenge of any anthology: what goes in, and what does not.

My expectations of the book shifted as soon as I read Larsen’s promise. I read and reread the contents listing to see how the editors’ selections fit with such a bold statement. I was thrilled to recognise many names, some of which I’ve mentioned above. Larsen and Knox have also included icons such as Bernard Beckett, Keri Hulme, Witi Ihimaera, Patricia Grace, Janet Frame, and Elizabeth Knox herself. But where is the Man Booker-longlisted Anna Smaill? Where is the Adam Prize-winning Kerry Donovan Brown? Where is the two-time winner of the Sir Julius Vogel Awards A.J. Fitzwater? And more besides.

The inclusion of stories by unpublished authors perplexed me. Not because I didn’t enjoy their work, but because many established speculative fiction writers struggle to find places that will publish anything other than realism in New Zealand. It’s exciting that VUP is giving a platform to emerging speculative fiction writers – I hope to see libraries and bookshelves around the country fill up with copies of Monsters in the Gardens and many more speculative fiction anthologies. My problem lies with how the anthology touts itself as a comprehensive selection of the best New Zealanders have to offer. This doesn’t fit with the exclusion of prize-winning and other established authors. Seemingly disagreeing with Larsen, Knox writes in her introduction, ‘What Monsters in the Garden is not is one of those state-of-the-nation literature anthologies. It’s an anthology among anthologies, and a good place to start.’

New Zealand anthologies of speculative fiction are few and far between, and genre writing rarely makes an appearance in established literary journals. Because speculative fiction hardly gets a platform, it is exciting that a well-established press such as VUP is featuring it. I so wanted the book to fully deliver on Larsen’s promise. However, if it was to be comprehensive it would have needed to showcase a wider range of the diversity, strangeness and far-flung surrealism of New Zealanders’ imaginations. Perhaps such a work couldn’t fit into a single volume – all the better for readers! VUP (and other publishers) could release a best of ghost stories, the most wonderful science fiction, and on and on until every bookshelf in New Zealand is bursting with weirdness. It would be fantastic if publishers release a number of ‘best of’ strangely imaginative fiction.

On the topic of how Aotearoa speculative fiction is rarely praised, both Larsen’s and Knox’s introductions touch on the fight for the legitimacy of genre writing in New Zealand. Writing competition prizes usually go to realist stories. As a younger writer, I remember editors of new literary journals urging my creative writing classmates to submit work. I’d ask if they accepted speculative fiction and they’d look at me as if I was a puddle they had stepped in. They were desperate, but not that desperate.

Non-writers are generally surprised when I speak of this dissonance between realist and speculative fiction in New Zealand. In university writing courses, students are sometimes discouraged if they bring hard fantasy or science fiction to the table. This causes imaginations to shrink. Maybe, if they’re lucky, they’ll squeeze in small elements of the genres they love – a tiny talking animal here, a gust of wind that could be a ghost, an unusual lizard who slips into the final paragraph like the dregs of the hope they once had for their work.

Knox outlines the various subgenres in speculative fiction, highlighting the breadth of the umbrella term, and she acknowledges that there isn’t a balanced representation of genres in this anthology. She notes that only “Keri Hulme’s ‘Kaibutsu-San’ might be classed as horror”. Hulme’s story is marvellous, as are nearly all the stories in this book, but I would have to respectfully disagree with Knox that Hulme’s story is the only horror represented. This anthology is full of terror and gore, whether it be the lichen wives with their dry mouths and empty stares in Tamsyn Muir’s ‘Union’, the cannibalistic Mickey Mouse in Phillip Mann’s ‘The Gospel According to Mickey Mouse’, the threatening Jimmy Jaspers in Gee’s ‘The Halfmen of O’, or the horror in the water of Craig Gamble’s ‘The Rule of Twelfths’.

Two of my favourite stories in the anthology fit the horror descriptor comfortably. Dylan Horrock’s ‘The Paresach’s Tulips’ is set in a fantasy world where a mage follows a trail of blood; she believes it will lead to an immortal killer. Jack Barrowman’s wholly original ‘The Sharkskin’ was full of so much tension that I felt as if I was reading Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw. When I started the story it was already late at night, yet I couldn’t sleep; I was unable to look away. I was terrified for the hunted sailors at sea. Barrowman’s line about a person’s intestines trailing after them like a tail made me so glad that I wanted to hug the page.

Larsen’s and Knox’s choice to distance their anthology from the horror descriptor gives a sense that they view the genre as inartful; this can’t be what Knox intended, given her well-known advocacy for horror fiction. And yet, their reticence to highlight the horror in Monsters in the Garden felt off. A good friend involved in Wellington’s Terror-fi film festival drew my attention to a qualifier that is popping up: “elevated-horror”. The Shining isn’t regular horror, you see, it’s elevated! As is Jordan Peele’s Us or Jennifer Kent’s The Babadook. This seems short-sighted, defensive even. Realism isn’t always “literary”, neither is romance always “trashy”, nor is comedy always “cheap laughs”. People need to stop attempting to elevate the art they enjoy when it relies on elements they’ve deemed beneath them.

I couldn’t help but be reminded of one of my favourite anthologies of speculative fiction, The Weird: A Compendium of Strange and Dark Stories, edited by Jeff and Ann Vandermeer. The anthology includes acclaimed authors Franz Kafka, Haruki Murakami, Angela Carter, and Kelly Link. It doesn’t shy away from marketing itself as horror.

I found myself frequently contrasting Monsters in the Garden with The Weird. Both market themselves as comprehensive selections of speculative fiction, but where The Weird takes the reader through a diverse landscape of subgenres, Monsters in the Garden stays in a few comfortable zones, with a bit of fantasy, some slipstream, extracts of historic science fiction. There are ghost stories upon ghost stories, all stacked up against each other, as if squeezing them together will cause the ectoplasm to solidify into one flesh-and-blood person.

Reading Monsters in the Garden felt like someone had given me a box of Cadbury’s Favourites, but I opened it up and found only Moro Gold and Flakes. I like both those things very much; I’ll happily eat them, but I was expecting more variety in a box that sells itself as a comprehensive selection of treats. As I say, perhaps this limited array is a sign that we need to better support New Zealand’s speculative fiction writers. There need to be more places for them to submit, more anthologies like this, and more judges of writing competitions who see merit in genre fiction. Every writing course should be a place where students and tutors delight in seeing how far people can wade into strange and dark waters. Let’s stop qualifying genre writing, and avoiding its descriptors. Speculative fiction is a wonderful art form in itself.

This review was originally published on the Academy of NZ Literature site.