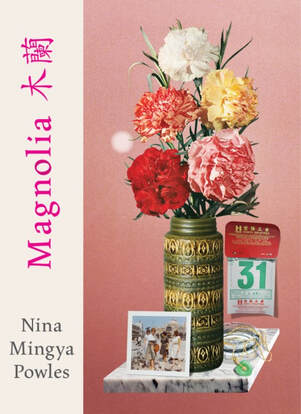

In ‘April kōwhai’ from Nina Mingya Powles’ Ockham shortlisted Magnolia 木蘭 ‘Home is not a place but a string of colours threaded together and knotted at one end.’ The collection bursts and drips with these colours as Powles explores what it means to be homesick; to be finding layers of meaning in the unfamiliarity of your family’s language, to be mixed-race.

The ‘string of colours’ is at times subtle, and other times overt, a way to describe the bright flashes — visual and emotional — that make up memory. The poem ‘Colour fragments’ begins:

On our way home from the botanic gardens, we dreamt of building

a museum of all the colours in the world, all the pigments and

what they’re made of, colours in their purest forms; a museum of

memories stripped down.

Colours, then, are the purest form of memory, and the poet desires to deconstruct these colours further, to make sense of feeling. This is clearest in ‘Two portraits of home’, where Powles takes inspiration from Werner’s Nomenclature of colours to list images such as the birds and trees of Aotearoa: ‘kōwhai-petal yellow’, ‘feijoa-tree green’, ‘tūī-feather iridescent green’, ‘fantail-feather cream’ and scenes of Shanghai: ‘electric-billboard blue’, ‘Shanghai-taxi blue’, ‘heart-of-jasmine pink’, ‘magnolia-leaf green-black’. The poem is in two parts, subtitled [IMG_098] and [IMG_227], but of course it’s not as straightforward as a separation into an image of each place. As with all ideas of home in this collection, there is overlap and connection, a sense that one flash of colour can spark a feeling from another time and place. The repetition of ‘the blue of the sounds’ in [IMG_098] and ‘hot violet’ in [IMG_227] give the reader pause to invest in those same stripped-down feelings.

Powles now lives in London, but wrote much of this collection while studying Mandarin in Shanghai, having previously lived there as a child and grown up in Aotearoa. Her idea of home is further ‘threaded together’ through recurring references, links to other women writers and warriors who have walked the streets Powles walked during her time in Shanghai, and the artists whose work she draws ekphrases from. Powles’ early work has also explored fictional and historical women. Here, she reflects on the New Zealand poet Robin Hyde’s experience in the poem ‘Letters from Shanghai, 1938’ and the life of writer Eileen Chang in the long poem ‘Falling city’, 32 numbered stanzas that read at times like journalled notes: ‘I imagine Robin Hyde and Eileen Chang crossing paths unknowingly sometime in 1938’ and at other times like the poetic realisations of someone exploring newness, ‘In each city, large or small, each person has their own secret map.’

Powles threads these real women’s lives into her collection along with links to contemporary artworks and movies. The opening poem, ‘Girl Warrior, or: Watching Mulan (1998) in Chinese with English subtitles’ sets the tone for a collection about finding those threads, relating to a place, a culture and female experience. Framed by the image of cutting one’s own hair, the poem describes watching the film and becoming the character, first through ‘makeshift costume’:

Halloween, 1999 / she unearthed a pink shawl from inside her wardrobe

cut a strip of purple silk to tie around my waist / bought a plastic sword /

gave me Hershey’s kisses

And later as a girl warrior in the world, ‘I no longer have a sword / but sometimes at night I hold my keys between my fingers’ — a universal symbol of women’s need for self-protection.

There are other hints at surviving alone in the world, including the loneliness of language. Magnolia 木蘭 is divided into three sections, the second — the eight-part poem ‘Field Notes on a downpour’ — is where this true exploration of language begins. Here Powles takes words apart and looks at how each character in Mandarin represents an image and each word created by these images can have multiple meanings. ‘Some things make perfect sense, like the fact that 波 (wave) is made of skin (皮) and water (氵), but most things do not.’

This is a poetic language of imagery and creation from which a sense of identity emerges:

五

The lady at the fruit shop asks me how I can be half Chinese and still look like this. (She

points to my hair). We come up against a word I don’t know. She draws the character in

the air with one finger and it hangs there between us.

“ juan”:

卷 curl

腃 to have tender feeling for

捐 to abandon

罥 a net for catching birds

At times like this, the theme of being ‘half-Chinese’, mixed-race, is lightly borne, leaving space for the reader to shift into the sense of not quite fitting. At other times, this feels less subtle, such as ‘Mixed girl’s Hakka phrasebook’, a poem divided into ‘Phrases I know in Hakka’ and ‘Phrases I don’t know in Hakka’, the first being simple numbers and responses, the second a longer list of more complicated questions and ideas, showing perhaps how hard it is to make meaningful conversation without fluent language. Later, too, ‘Alternate words for mixed-race’ gives a footnoted list including criticism of someone learning to write their own name.

But perhaps readers need these more self-conscious poems to highlight the subtlety of the others, just as those of us with mixed-race backgrounds are always explaining our origins and the correct pronunciation of our names, as if everything we do hinges on this understanding. The most effective poem on this theme is ‘Mother tongue / 母语’ a poem in two voices, considering the present time where:

I peel jackfruit with my fingers

while they talk over and around me

in a language so familiar but so far away

and the imagined alternate life:

if I had grown up here

I would have different-coloured hair

and different-coloured eyes

I would speak to Popo all the time

we would chop vegetables together

and peel the shells off quail eggs

on blue evenings we would sit

looking out for distant lightning

above the hills where plastic flowers

fall against coloured graves

see how it lights up her face

as the rain cools off the surface

of my skin

of this dream

where I am not trapped

in any language

At the heart of this displacement is the sense that learning the names of things, making the food and experiencing the seasons are key to finding oneself. The stickiness of this immersion comes back again and again: the tastes, smells, heat, rain and steam of somewhere growing more familiar to both poet and reader. The ‘heavy, humid air’ and ‘scent of tea and rice and wet leaves’ in ‘Love letter in lotus leaves’ reveal the texture of elsewhere. The poem takes us through the careful creation of zòngzi — sticky rice dumplings wrapped in leaves and steamed — ‘Fold them in tight parcels / as if wrapping small gifts. Tie neatly with string.’ This is an act of love and of claiming or reclaiming one’s heritage. The poem ends with:

white unwrapped cakes

of steamed ricebear the imprint

of ridged leaves

azaleas bear the memory of rain

Each tiny parcel, each step towards understanding how things are wrapped in this new place, brings the poet closer to feeling at home there.

Powles’ voice is the thick steam on kitchen windows and the bright hues of a rain-soaked city. She is a poet who clearly works hard at her craft and Magnolia 木蘭 is a confident and cohesive collection, firmly threaded and knotted with obsessions that are both deeply personal and entirely relatable to anyone who has felt separate from their home or their heritage.

This review was originally published on the Academy of NZ Literature site.