People have been putting flowers at the base of the Llew Summers sculpture, Peace, on Colombo Street in Christchurch. There are dried-out flowers and there are fresher ones too; at the time of writing (August 22), this had been going on for days. For a second, I wondered if these were tributes that anticipated the tenth anniversary of the devastating cycle of Christchurch earthquakes. Or could they be marking the sentencing of the Australian gunman who murdered 51 people at two mosques in the city last March? Peace, after all. Then it clicked. They were probably put there to remember Summers himself, a much-loved local figure who died a little over a year ago and whose life story has been told by poet and cultural historian John Newton in a book also timed for the first anniversary of his death.

Summers was world-famous in Christchurch, but less well known outside it. Even those who didn’t know his name in Christchurch knew the large, generous work – chunky figures dancing together near Linwood College (Joy of Eternal Spring), four doves forming a circle in Sydenham (Peace), the guerilla-like, overnight appearance of works in public places back in the 1970s and, of course, the art controversy that accompanied the commission to create Stations of the Cross for the city’s glorious, since-ruined Catholic cathedral.

You’re not an artist in Christchurch until you’ve had a good old-fashioned art controversy. Frances Hodgkins had one; Michael Parekowhai had one; Andrew Drummond had one and Summers had several. The routine narrative of these controversies usually involved repressed, close-minded officials who couldn’t see the artistic value of whatever was directly in front of them, or were shocked by its sexual or blasphemous content. Sometimes it was all of the above. (The city even rejected a Henry Moore sculpture of sheep because it didn’t look enough like sheep.) Art controversies erupted in the letters pages of the city’s daily papers, especially the then-conservative Press, which spoke for the Christchurch establishment. It wasn’t just Christchurch, either – Newton has unearthed the letters, cartoons and even poems that ran for weeks in the Upper Hutt Leader when Summers’ Maternity was installed in Upper Hutt in 1979. ‘It wouldn’t be so bad if she wasn’t so fat,’ one complainant said about the giant figure of a naked woman cradling two children. Others tut-tutted that there was a mum but no dad.

In Timaru, someone threw red paint over a work called Tranquility. That’s an apt title considering how this book unfolds. If those and other problems bothered Summers as he made his name as an artist in the 1970s and 80s, there was little sense of struggle when Summers eventually told his life story to Newton over two intensive months in 2019. The background is that Newtown came south for a University of Canterbury fellowship. Learning that Newton had nowhere to stay, Summers offered him the use of an artist’s residence he built on his property. Such kindness was said to be typical. When Summers suddenly and unexpectedly became sick, there was a writer on hand to record his biography.

This is a very Christchurch story, and not just because of the artist’s local fame. Political and religious nonconformism has always been important in Christchurch, and it complicates the genteel stereotypes of the ‘more English than England’ garden city. Summers’ parents John and Connie were well known in political and literary circles. John ran a bookshop and championed artists and writers; Connie was arrested five times during the anti-tour protests in 1981 (she was in her sixties). Both were socialists and pacifists. Tony Fomison was a family friend who encouraged the young, self-taught Llew Summers.

The John Newton who wrote about the Baxter commune at Jerusalem in The Double Rainbow, and who is writing a series of studies of 20th century New Zealand literature is more than equipped to tackle a relatively straightforward life story that also intersects with important moments of cultural and social change. Summers’ inheritance of the domestic violence he witnessed as a child illustrates the wider struggle of an entire cohort of New Zealand men of his age. More could have been said about what it meant to be male in this country in the 1970s and 80s. Newton shows how the ‘naked earth mothers’ Summers produced in the 1970s were shaped less by hippie fetishism than the artist’s guilt and anxiety about being a single dad after he had driven his children’s mother away. ‘They spoke of his pain and resentment, but also his longing,’ Newton writes. This is valuable biographical information that shows how art sprang from life. Similarly, Newton tracks the angel imagery that appeared in Summers’ work in the early 2000s to the death of his partner Rose. There is a sense of a very public man with some highly private reasons for making the work he did.

Like his mother, Summers was also arrested in 1981. Two police officers took him to a cold, empty room in the central police station where he was stripped and interrogated, and possibly assaulted. (According to Geoff Chapple’s 1981: The Tour, ‘He was struck in the throat, his foot stamped on, held by the hair against the wall, his beard tugged at.’) More than two decades later, the humiliation found its way into what could be Summers’ greatest work, his Stations of the Cross.

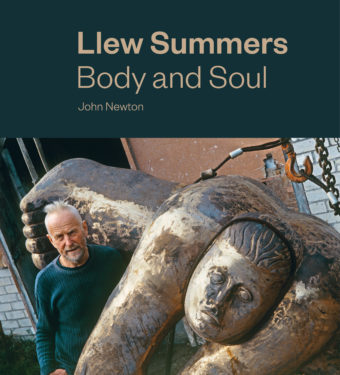

The work was controversial in Christchurch because in one of the 14 scenes, Christ is depicted as naked. But it is not an irreligious or scurrilous work. Like McCahon and Michael Smither, Summers found a local art language that fit the Biblical stories, celebrating the persistent power of life as well as recognising inevitable loss. Like them, he had his own personal relationship with religion that his work explored, in defiance of a largely secular culture. ‘We’re given a soul and we’re given a body,’ Summers used to say, giving Newton the inevitable title for a sensitive, empathetic and liberally illustrated study that finds a good balance between the man and his art, and shows how ‘in sculpting the body his ambition was always to release something more – an energy, a vitalism’. Clear and undogmatic, Newton’s writing renews work that some of us have even come to take for granted.

This review was originally published on the Academy of NZ Literature site.