Denis Glover’s place in New Zealand literature is assured. Along with R.A.K. Mason, A.R.D. Fairburn and Allen Curnow, he was one of those who revitalised New Zealand poetry in the 1930s. It’s understandable that his ‘Sings Harry’ and ‘Arawata Bill’ cycles continue to appear in anthologies. ‘The Magpies’ still takes the prize as New Zealand’s most-often-reprinted poem. In founding the Caxton Press, Glover turned this country’s publishing industry in a new direction, making it possible for poetry and fiction of high quality to reach a wider readership. Throughout his life, he was an acute critic in matters of printing and typography.

But regrettably there’s the very negative side to the man. As Sarah Shieff makes clear in her introduction to Letters of Denis Glover, ‘drunkenness and a deep vein of self-destructiveness … cost him almost everything: his first wife and only child, the Caxton Press, and a subsequent job at Albion Wright’s Pegasus Press.’ Alcoholism, erratic behaviour and his womanising were accompanied by a decline in his writing. His later verse in no way sustains the quality of his earlier efforts. Shieff notes ruefully ‘to many, Glover has become little more than a tiresome anachronism, a misogynistic old fart, court jester, a drunken laughing stock…’

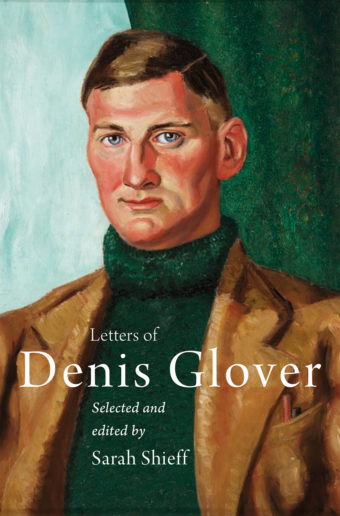

Following the pattern of her earlier Letters of Frank Sargeson, Shieff’s Letters of Denis Glover is not The Letters of Denis Glover. As she explains, from an archive of 3000 letters which Glover wrote to about 430 people, she has chosen 500 letters to 110 people, whittling away the less significant and more ephemeral. She organises these 500 letters into eight sections, covering key events in Glover’s life ranging from a 1928 letter written when he was a schoolboy to letters written days before his death in 1980. At one time or another, Glover corresponded with most of the important New Zealand literary figures of his time. There are many letters from Glover to Curnow, but Shieff selects the letters to Frank Sargeson as ‘the most engaging, the widest ranging, the liveliest’. Shieff makes intelligent use of footnotes to explain Glover’s erudite allusions or bawdy puns and to clarify topicalities that are no longer topical. In many cases, she also quotes parts of letters sent to Glover, giving context to Glover’s responses. After what must have been long and painstaking research, this is an exemplary exercise in selection and editing.

Reading a collection of letters like this, we always have to ask how much the letter-writer is really confiding in friends, and how much is intentionally a sort of public performance. And obviously, even when discussing the same matter, Glover will readily adopt a different tone depending on whom he is addressing. In letters written to Ursula Bethell in 1936 and 1939, he is courteous and formal, discussing the publication of her poetry. But later, writing to Charles Brasch (19 April 1940) he says sarcastically of Bethell ‘The dear author would supervise every detail in a way that only Anglican spinsters have; this is not cruel comment: merely exact’.

With his closest friends, Glover readily expresses his prejudices. He never likes Catholics – which feeds into his contempt for James K.Baxter in his Catholic phase – and makes occasional jocular slurs about Jews, repeatedly referring to New Zealand Breweries as “Jew Zealand Breweries”. This is an unexpected prejudice, given that his wartime lover, Dvora Elkind, was a Russian Jew, and given that he much later took Israel’s part in a dispute he had with Curnow, who favoured the Palestinian cause. Then there is that crude, misogynistic strain. Glover usually belittles women writers (Robin Hyde, Eileen Duggan et al.) and appears to be particularly allergic to Katherine Mansfield. Writing to Sargeson (10 February 1948) on a forthcoming book about Mansfield, he declares ‘The Coming Generation ought to have the opportunity of at least dismissing her… there might be some minor interest taken in the girl once again.’ Thirty years later, he’s still banging the same gong. To Ian Gordon (23 April 1978) he writes that ‘professors’ practise ‘necrophily with our much ravished clever schoolgirl KM’.

The humour, such as it is, is jokey-blokey and laddish, often sounding like a schoolboy trying to impress his mates. This is truest when he is writing to A.R.D. Fairburn. On the birth of his son, he begins a letter to Fairburn (15 September 1945) with a laddish boast: ‘Yes, in sooth, I have a sonling. He is lusty, red-headed & hot tempered; and at 7 weeks his private parts are of such stupendous magnitude that I fear greatly for a little girl-child or two lying all unknowing in some cot elsewhere.’

Yet despite this masculinist twaddle, there’s the irony that Glover was loved by many women, from his first wife Mary Granville to his last Lyn Cameron, and in between his long relationship with Khura Skelton, as well as affairs with Olive Johnson, Janet Paul and others. In this collection, there is an extraordinary number of what a much earlier generation would have called ‘mash’ letters – kittenish courtship and verbal seduction of various women. As Sarah Shieff remarks,

Glover was without a doubt a feckless lover and an incorrigible drunk, but his letters also reveal a seductive charm. These intelligent, attractive women were clearly able to look past the grog-blossom complexion, terrible teeth and cauliflower ear.

Sometimes, even when declaring his love, he can’t restrain the jocularity. Writing (1 April 1970) to Janet Paul, who briefly considered marrying him, he says,

Of course the whole plot is ludicrously Victorian. Reformed drunken and penniless poet latches on to mother-mistress figure of soft-hearted widow woman of some means and large family. Practises daily saying meekly ‘Yes, dear’ to his shaving mirror.

But he does show some self-awareness of his failings as a husband and lover. To Dvora Elkind (14 August 1951) he dissects the breakup of his first marriage and confesses ‘Love my wife madly, of course, but we now have legal separation. Both fools. 80% my fault, 20% or less hers.’ Indeed, there’s an extraordinary ambiguity to some of his foolery about women.

The epitome of this is his response (28 February 1956) to a really wrenching letter Frank Sargseon had written about the mental health of Janet Frame. Glover’s reply at first seems callously jocular about Frame, even suggesting she could solve her problems by suicide; but read on and you see he has considered her state carefully and really does ask Sargeson some searching questions about the situation.

On top of this, there’s no denying Glover’s literary brilliance. Between 1942 and 1944 he writes letters about his war experience in the Royal Navy, including his time aboard HMS Onslaught, escorting convoys to Murmansk, and his role in the D-Day landings. This is excellent, vivid, colloquial reportage, which he was later able to turn into publishable narrative. When he wasn’t nursing his prejudices, he was a very perceptive reader. Presented with manuscripts by the then-unknown Janet Frame, he immediately declares ‘I have not seen anything quite so unaffectedly natural and at the same time incisive for a long time,’ and offers to publish (Letter to John Money, 24 January 1947). In the 1970s, in his exchanges with Curnow about the presentation of Curnow’s latest collections, his remarks on typography are always informed and precise.

From the 1960s onwards, however, these letters suggest that Glover was getting more and more out of step with recent literary developments. He becomes more sceptical of the poet’s art. To Charles Brasch (16 December 1962) he writes,

Writing verse for its own sake is a fine and private game: publication is so fatal. Think of all the wonderful things that have never been written! Once when D’Arcy [Cresswell] was moaning that he hadn’t written anything for months, Bob Lowry said ‘Never mind. You are a poet. Why write the damned stuff?’

He welcomes Robin Dudding’s setting up Islands as an alternative to Landfall and offers advice to Dudding (5 August 1973), showing his increasingly conservative poetic when he says he is tired of reading learned articles by young academics : ‘Let the earnest-minded little undergrads get their PhD’s as they may, later, later. Meantime discourage them from writing verse.’ To Anton and Birgitte Vogt (6 June 1975) he says ‘Olding but not balding, I become a sort of Marris, Mulgan, Schroder of this age’ referencing the conservative literary editors whom he ridiculed when he himself was a young man. He goes on to claim that the younger poets (Alan Brunton, Sam Hunt etc.)

… are discovering poetry as a fresh invention, totally oblivious… of the rolling stream of English literature, with all its eddies and whirlpools. Knowing nothing, they just don’t know our tremendous debt to Rome, Greece and Italy… I shrug – but let the mummers have their day, the wind will blow them all away.

To Olive Johnson he says bluntly (5 May 1977) ‘I avoid NZ literature; and its self-puffed poetry is a stew lacking but grease and meat.’

Much of this is Glover in grumpy old man mode, but he may also be desperate old man, aware of his own sinking powers as poet. To Sargeson (26 December 1974) he notes the ‘doggerel’ he is now writing for the press and admits ‘I am depressing my sights. Retirement leaves me little time to tickle the Muse seriously.’

Taking us from schoolboy notes to hearing the chimes at midnight, Letters of Denis Glover gives us, in effect, a biography of Glover almost as comprehensive as Gordon Ogilvie’s Denis Glover: His Life. It certainly gives us more of Glover’s own voice than any other publication has. One little warning, however. It might be advisable to treat Letters of Denis Glover as a reference book or a text to be dipped into. Read one by one, his letters are often witty, erudite, sometimes almost surreal in their tortured and forced puns and their topical in-jokes. But read en masse they curdle – the joking becomes a predictable affectation and facetiousness. Do not do as I have done, making my way through it all in a week. Give these letters space to breathe.

This review was originally published on the Academy of NZ Literature site.