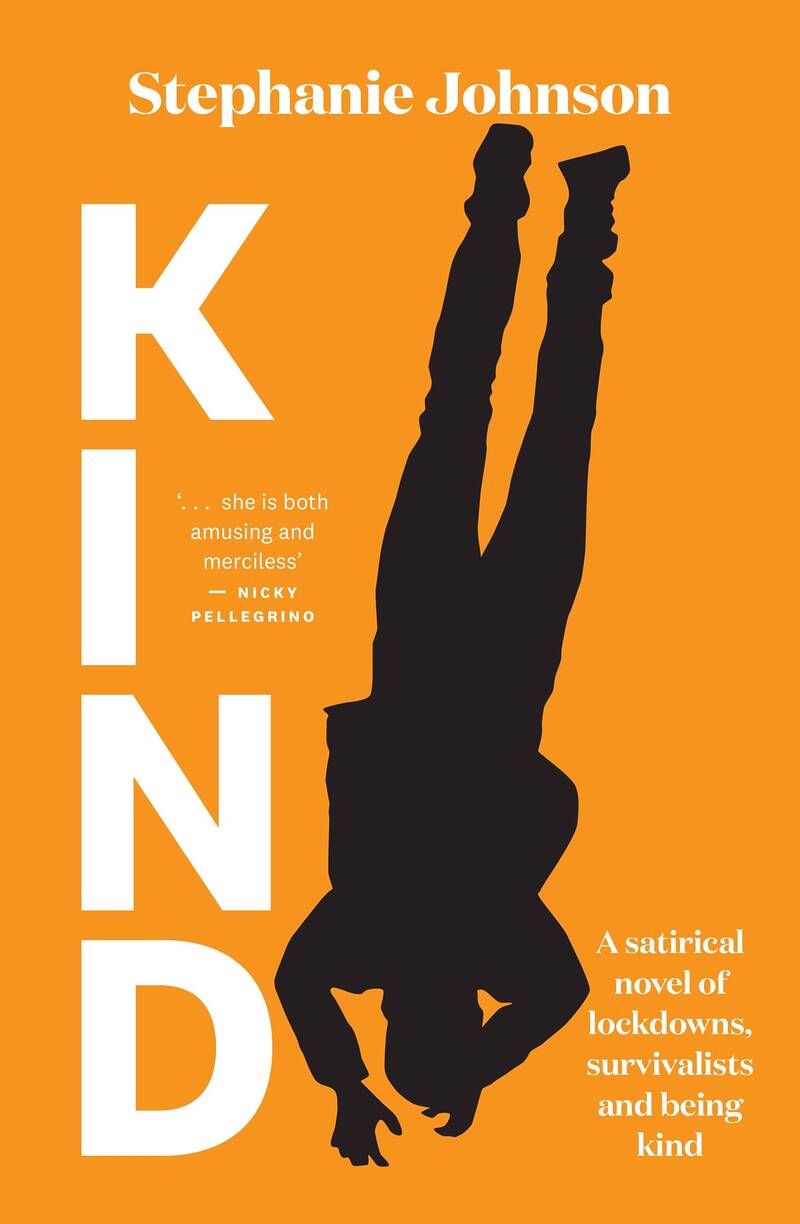

In an afterword to her new novel, Kind, Stephanie Johnson mentions a lecture she gave at the 2021 Auckland Writers Festival, in which she predicted ‘a pandemic of work centring on the coronavirus crisis.’ Kind, she writes,

is my contribution. I wrote it as an entertainment, both for myself through those confronting, difficult months of successive lockdowns, and also for my future readers to enjoy when the early 2020s are consigned to memory.

The Covid pandemic is recent enough to evoke vivid memories, yet sufficiently distant that we can revisit, in Kind, lockdowns, bubbles, social distancing and closed borders with wonder at their strangeness. How easily we adapted to the new normal. We gave away rituals and comforts we thought we couldn’t do without. We even wondered, after we were allowed back, whether we really needed the local café. (Answer: yes, we did. Pretty soon we were addicted it all over again.)

It was intense. In Auckland the drought went on and on, the streams dried up, the grass in the parks turned yellow. Those who had lost their jobs were crushed; those with young children who had to work by Zoom went berserk. We lived in a dream of sun, silent streets, overseas death stats.

The sense of dislocation. The stories. As an old woman lay dying, her children had to stay two metres away. A lockdown wake: groups of family bubbles in the forecourt, talking through car windows. The funeral procession, the skies hard cloudless blue, the streets so empty and silent it seemed as if the whole world had stopped for the dead.

There’s a point to this. It was an extraordinary human situation. All our interactions were rendered strange. We grappled with terror of the unknown, fear of contagion. We felt the kindness Jacinda kept urging on us, but we struggled to express it. We wanted to rush to help, and we had to keep apart.

This is the point. Wasn’t it weird enough? The answer to that question, perhaps, is an aesthetic one.

Kind is a novel with a cast of characters large enough that concentration is required to sort out the relationships. There are numerous complexities. The novel moves about in time and place, but centres on a period of Covid lockdown.

Kerry-Anne has left her husband Lyall, a National MP, and has travelled with Mamie, her small daughter, to Russell in the Far North. She is spending lockdown peacefully with her parents, but soon her foster sister will arrive, bringing danger. Joleen has always been trouble. She’s unpredictable, anarchic and a criminal.

While Kerry-Anne is dealing with Joleen, Lyall, the ex-husband, gets sick of brooding alone, and decides to embark on a bike ride that will take him into the South Island high country. Their friend Mick is in the picture too. He is a private investigator who will soon turn his attention to Lyall, Kerry-Anne and Joleen, and the difficulties brewing between them.

So Kind opens, setting out its scenarios and hooks, promising the satisfaction of complicated relationships and intricate connections, in the strange time of Covid. The plotting is intricate. It becomes clear there’s illegal activity going on, from breaches of lockdown, to a criminal enterprise, to a series of violent crimes.

The strongest writing and the most exciting thread initially involves Lyall. He hasn’t told anyone where he’s going; he’s pitting himself against the elements, his isolation made more intense by the lockdown. Many readers will be familiar with the vast, extraordinary landscape Johnson describes. You’d think his situation would be striking enough. You’d think so, and then something happens to Lyall that is so grotesque, so implausible …

Is it a thrilling development? Perhaps the answer to that is simply a matter of taste. It is, to attempt an explanatory analogy, as if the author has driven into Mt Aspiring National Park, looked around at the grandeur and the drama and the wildness and the beauty and announced, ‘What this place really needs is a Ferris wheel. And a merry-go-round. And a horror-themed funhouse. Because that would make the place fun, wouldn’t it?’ Wasn’t it wild and beautiful enough? Aren’t real human interactions strange and compelling and complex enough?

Publicity for Kind describes the novel as ‘fearless and funny’, and the author as having an ‘eye for topicality.’ Its blurb asks, ‘Will anyone come up smelling of roses?’ Individual readers will decide whether it’s funny. As to topicality, various elements raise questions of authenticity. Presumably this is deliberate. There’s a lesbian couple: one is old and white, the other was underage when they met and is black; they are both mentally ill and their behaviour is sadistic. A character makes two false allegations of sexual assault. There is a special emphasis on ‘locking people up.’ One character (the daughter of a violent gerontophile) drugs another and locks her in a house, forcing her to escape from a window. (It must have been a very unusual house.)

At one point in lockdown Lyall has had enough:

Endless sickly memes about cats and kids and fortitude and loving and being kind. Particularly, kind, and if he saw that four-letter word again he’d punch holes in the walls… Kind. The Prime Minister was always saying it. Be kind. What a joke. Nothing in this world was kind.

Perhaps the author is saying, fearlessly, that we are all too sensitive, with our trigger warnings and our intersectionality. We are too hung up on kindness. Again, readers can decide. But there’s that other broader question: of aesthetics. Think of a writer like Alice Munro, say, who has that uncanny ability to look beneath the surface of words, to notice what a facial expression means, to mine the everyday for subtleties that add up to something thrilling or savage or meaningful, and to convey it with skill that is deceptively simple and quiet, but that can hit you with real force. Is that kind of writer just out of fashion? In these frenzied End Times, do we all just have to go blockbuster, because the world is too insensitive now, too glazed with chaos and screen time, to absorb anything that could be called art?

Sometimes the greatest exercise of the imagination involves stillness, observation, careful thought. Analysis, subtlety, attention to what lies beneath. But are we over with all that? The imagination is often best applied to what is, not to what might be. Do we wonder what’s going on behind that person’s eyes? Or do we forget about using our imagination to understand and describe – and just conjure up a unicorn? Or two insane lesbians in a bunker. In human and artistic terms, wasn’t a lockdown at the far end of the world enough? Why the funhouse? This is the aesthetic question posed by Kind.

Just as you can brush up on politics and write about it without turning out a gun and tech-filled pulp thriller that ends in a blood bath, you can also write about a pandemic without inventing added horror. You can choose aesthetic restraint or you can go blockbuster. It’s up to the writer, and to readers of course.

It’s a matter of taste, but maybe one of skill, too. It is perhaps harder to convey with subtlety than it is to fill your story with bunkers, villains, nutters, houses in which people can be imprisoned, psychopaths, sadism, grotesqueries, all the kitsch you can pack in. But perhaps subtlety is just boring and hard. In these times of crisis, maybe we’re all just losing our minds wanting fun.