The short, intense life of the writer Robin Hyde – born Iris Wilkinson in 1906 – was difficult, and writing about that life for a younger reader is difficult as well. There’s drug addiction, a suicide attempt, recurring stints in mental hospital, and two pregnancies considered to be shameful secrets; one of the fathers was married, and the other married another woman before Iris, traumatised by the stillbirth of their baby in Sydney, returned to New Zealand.

Crippled in one leg in her late teens (the start of her reliance on pain meds), Iris was besieged by inner demons too: she was acutely sensitive to noise, as well as perceived slights; she dreaded the darkness and was tormented by insomnia, as well as exhaustion from over-work. Her family and (sympathetic) doctors described her as emotionally unstable. She could get ‘angry and violent’, Frank Sargeson recalled after her death. While she was alive, Sargeson and other lit-world frenemies like Denis Glover sniped at Iris behind her back: her 1936 book Passport to Hell was ‘obscene’ and ‘bad prose’; its author was ‘Robin Hyde, the silly bitch’.

Iris also faced the ongoing battles and precarious existence of a young female journalist in the Depression era, moving from Wellington to Christchurch to Whanganui to Auckland in search of work that entailed long hours and low pay, with assignments that often felt dispiriting and banal, living in boarding houses or baches. This economic anxiety turned to desperation: the foster parents raising her small son needed funds that Iris struggled to supply.

Her long-planned trip to the northern hemisphere, where she hoped to make money and return triumphant, resulted in more trauma, psychic and physical, at the frontline of Japan’s brutal invasion of China, then more hospital stays to treat injury and disease, in Hong Kong, Singapore and London. In the last year of her life, 1939, Iris published the book Dragon Rampant, her account of the war in China, but London was preoccupied with the fascists in Spain and Germany. She died, of Benzedrine poisoning, in her rented room just weeks before the outbreak of the Second World War. Iris was thirty-three years old. The son she’d left behind in New Zealand, Derek Challis, was eight.

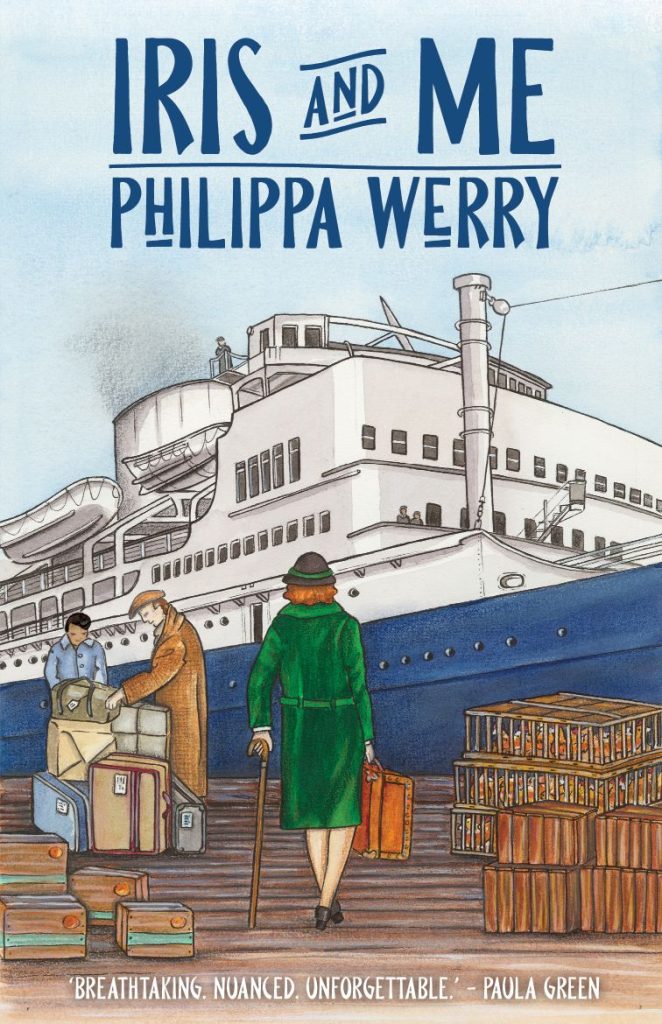

Iris and Me, Philippa Werry’s verse novel written for young people, is prefaced with the number for Youthline and other services, and warns that this ‘book deals with themes of depression and suicide’. (They are not themes, of course, but the facts of the subject’s life.) Werry’s approach is to frame Robin Hyde as a heroic figure who must struggle with physical and mental challenges, as well as narrow societal expectations, in order to write books, report on a war and climb every mountain:

She was brave

unconventional

passionate about the power of words,

used them

shaped them

into new creations.She wanted – what do we all want? –

to be loved, to be worth loving.

But she could be touchy as a porcupine

and her sharp tongue often scared people away.

Both this tone and the book’s central conceit, keeping readers guessing for more than fifty pages about the ‘me’ who narrates the story, suggests a young teen audience. For this reason, perhaps, Werry blurs some of the harder edges of Iris’ life. She describes the Wilkinson family home as ‘a house full of love’ and then with a little more accuracy as ‘that loving, tumultuous household/where arguments burst out of the walls’. Iris’ parents married in haste and repented at leisure, one in thrall to Kitchener and the other to socialism.

An even blurrier take: Iris’ suicidal leap into the harbour in June 1933 was followed by three months at the Grey Lodge, described here as a ‘sanctuary’ that was part of ‘Auckland Medical Hospital, Avondale’. Afterwards she visits the family home in Wellington for a ‘quick visit’. The real story is much messier and unhappier. ‘Auckland Medical Hospital’ was actually Auckland Mental Hospital, either a typo or a curious re-naming in a book that must deal, explicitly, with the mental health of its central figure. Iris was removed from the Grey Lodge when she was caught smuggling in morphine and transferred to a large ward in another building. Her mother was summoned; Iris complained to the superintendent about how degraded she felt because of the loss of her privacy, and she began refusing food.

After a month Iris was permitted to return to the Grey Lodge, but Dr. Gilbert Tothill – named by Werry as one of Iris’ ‘two guardian doctor-angels’ – described her as unstable and uncooperative; her attitude, he said, was one of ‘antagonism’. Iris was determined to be discharged but her physical and mental state were so bad that her mother had to take her back to Wellington. After just two weeks Iris returned to Auckland, to stay with Derek’s foster parents, because she needed to earn money from freelance writing. No wonder by December ‘Iris fell to pieces again’, as Werry notes, and returned to the Grey Lodge. It was her home on and off for almost four years, its attic a space where she worked on an implausibly large number of books, poems and journalism. Iris and Me conveys just how driven she was as a writer, how necessary writing was to her life and sense of herself, far beyond making a living.

The book’s focus is 1938, the year Iris sailed away from New Zealand forever. The narrative keeps returning to this journey, with its various ships and ports and people met along the way, exploring Iris’ fateful decision to re-route herself to ‘Shanghai, the backyard of the war, … an occupied city’ and then to the front. The war sections set in China are the strongest in Iris and Me: Iris hides from the ‘screaming dive/the quake and thud of a bomb dropped’ and sees soldiers ‘bayoneted where they lay’, as well as bodies on the streets of Shanghai, killed by ‘starvation, smallpox, measles, cold’ and carted away ‘on corpse wagons’. In a book that seems to shy from the words ‘Mental Hospital’, the descriptions of Iris’ experiences on the front line in China – and her perilous attempts to escape – are visceral and imaginative:

Dead bodies

lay strewn under the tracks

unburied, some chewed by dogs.

Their clothes torn and bloody,

flesh turning an odd colour,

streams of ants and beetles

scurrying into their nostrils and open throats.

Before Iris left on her doomed odyssey, she was a mother who was prone to doting and disappearing, her energies consumed by earning money for her son’s upkeep. In Iris and Me we’re told that Derek ‘had grown up knowing/that Iris comes and goes’.

She saw Derry when she could,

bought him coats and clothing when she could.

For his fourth Christmas, she made him a

book of rhymes, by his own Mother

who hopes to have them printed

with funny pictures,

one fine day.

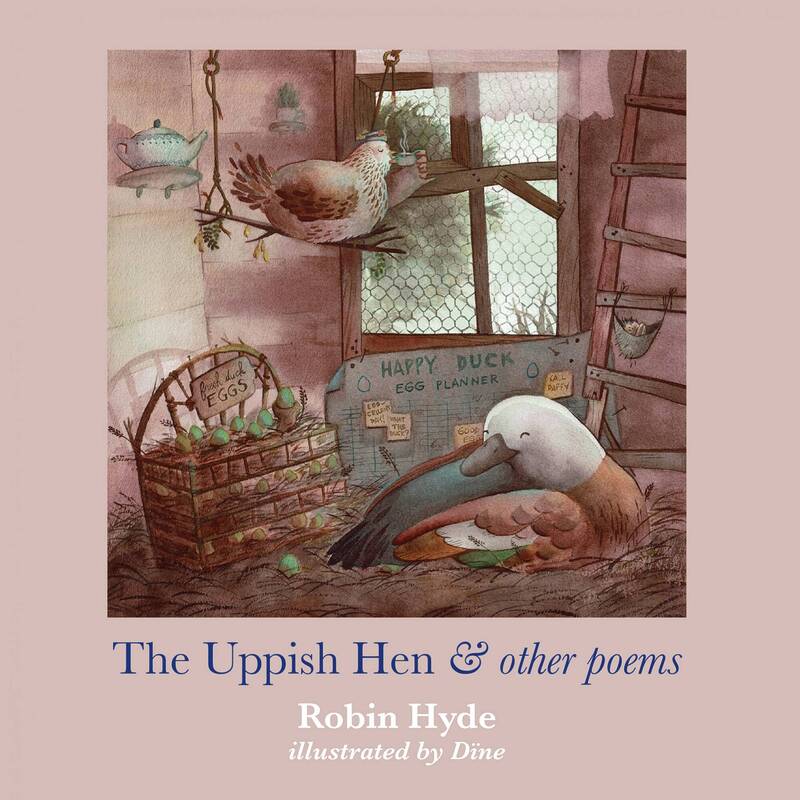

Now all but one of the seventeen poems in Derry’s Rhyme Book, given to Derek Challis in 1934, have been gathered into The Uppish Hen, edited by Juanita Deely with illustrations by French-born artist Dïne. This is a handsome collection, its colour pictures (mostly of creatures) whimsical, detailed and old-fashioned in a way that suits and supports the poetry.

Because the poems are almost ninety years old, they present a different sort of challenge for the (even) younger reader. Deely is the writer and director of A Home in this World (2018), a film based on the life of Robin Hyde, and she dedicates The Uppish Hen to Derek, who ‘gave his blessing to this book’ before his death in January 2021. Clearly it was created for him, and Deely laments that ‘it can’t be put in Derek’s Christmas stocking as I’d intended’.

A contemporary child may be puzzled not only by the diction (‘a shadowy tide o’erpast/and a world painted rosy with morn’) but the vocabulary, from ‘marrow-bones for tea’ to flues, mazurkas, bell-wethers and ‘the tourmaline of sunset’. A tūī (now with added macrons) appears in one poem, but the others are thronged with foxes, weasels and badgers. This evokes the world of The Wind in the Willows (published during Iris’ own childhood) rather than the New Zealand in which Derek was growing up, let alone the country a century on. Some of the language of the original manuscript has been modified to account for contemporary sensibilities: in the poem ‘Singing’, the gypsy is now ‘a traveller’ and the Spanish sailor is now ‘salty’ rather than ‘swarthy’, though the latter is not a pejorative term.

Some of these poems appeared in Young Knowledge, a collection of 300 poems by Robin Hyde, edited by Michele Leggott. But completists, obsessives and scholars will still want to own The Uppish Hen, even if their children engage more with the pictures than the words. The most poignant poem in the book is ‘The Dream Child’:

Dream that a wee head lies by your own,

Soft dark ringlets by curls of gold,

Dream you can hear, Little-Boy-Alone,

Sweet child laughter that never grows old.

This suggests Iris’ stillborn son, Christopher Robin Hyde, seen here as golden-haired Derek’s invisible companion. It reminds us that Iris lived and travelled with her ghosts as well as her demons, her dreams as well as her afflictions – with both her names, and both her children.