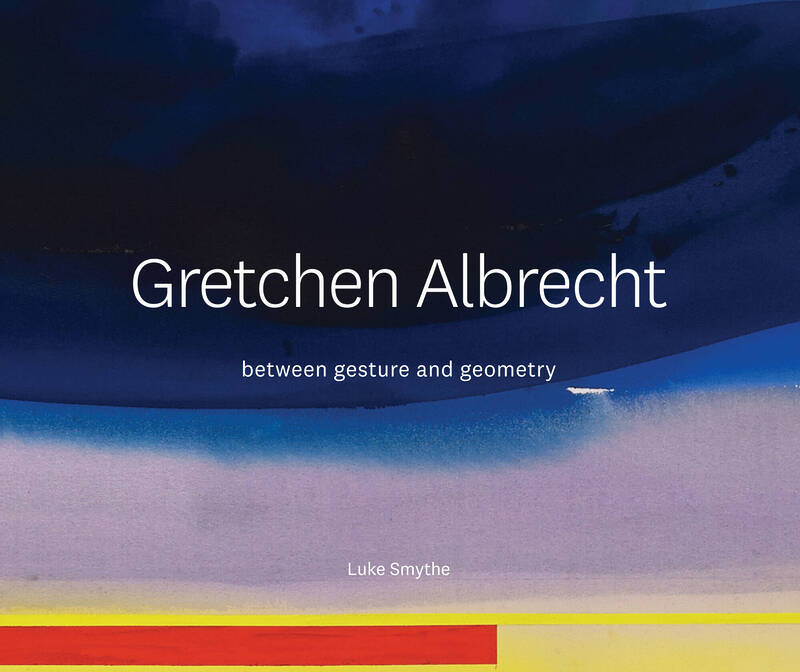

The first edition of Luke Smythe’s Gretchen Albrecht: between gesture and geometry was published in 2018 and unsurprisingly sold out. This new edition this is more than a reprint: the numerous changes include a final chapter, ‘Time’s Measure’, which covers the years 2019–2022 and features twelve new full page reproductions of the paintings from that period.

Albrecht’s art is distinguished by its extraordinary orchestrations of colour and this new edition – with 170 full-page colour reproductions – reflects that. Luke Smythe has an intensive knowledge and understanding of Albrecht’s work. The writing about her paintings and collages is thoughtful, intelligent and measured; he contextualises them well in relation to both the New Zealand art world at the various stages of her long career and practices and trends internationally, especially in America and Europe. The only perplexing note is the epigraph, quoting John Berger: ‘Poetry’s impulse to use metaphor, to discover resemblance… is to discover those correspondences of which the sum total would be proof of the indivisible totality of existence’. Does such a condition as the ‘indivisible totality of existence’ actually exist?

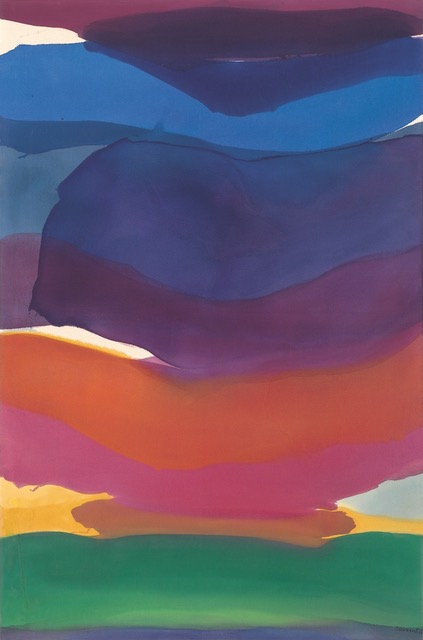

Poesia (3) 1989

acrylic and oil (with collage) on canvas

I’ve known Albrecht’s art since her first exhibition at the Ikon Gallery in Lorne Street, Auckland CBD, in 1964, yet from Smythe I learnt a lot that I either did not know or had not thought about. Our ‘art world’ in New Zealand is small, so full disclosure: since 1983 I’ve written several articles and catalogue essays on Albrecht’s work and for her most recent exhibition, Lighting the Path (17 November–2 December, Two Rooms Gallery, Auckland), I wrote the gallery text; at the accompanying launch of I gave the inaugural speech. To complicate matters further, I’ve known Smythe since he was a child. Could there be any more conflicts of interest? I’ve approached this review as a set of reflections stimulated by a book that explores prime aspects of Albrecht’s art and its relationships with art-making in New Zealand generally.

In my opinion, Smythe’s work is the best and most comprehensive piece of writing on Albrecht’s art and career. Smythe is a senior lecturer in Art History at Monash University in Melbourne. Born in Auckland, he graduated with a BA in art history and philosophy from the University of Auckland, then moved to the US for an MA at Columbia University and a PhD in Art History at Yale. His thesis focused on Gerhard Richter (born 1932), also the subject of his book Gerhard Richter, Individualism and Belonging in West Germany (Routledge 2022). Smythe has now been commissioned to write a monograph on another leading – and complicated – German artist, Sigmar Polke (1941–2010).

Smythe’s updating of Gretchen Albrecht includes extended descriptions of Illuminations, a series of works from the late 1970s. These paintings had never been framed, let alone exhibited. Indeed, Albrecht had forgotten about them. The designation Illuminations could well be extended to most of Albrecht’s works from the early 1970s. The choice of title and focus were informed by Benjamin Britten’s Les Illuminations, a musical work inspired by prose poems by the French poet Arthur Rimbaud, written in the early 1870s and first published in 1886.

Illumination, 1977

Rimbaud’s Illuminations are strongly visual, and his words also evoke colour and music. Along with A Season in Hell, they were widely read in 1960s and 1970s counter-cultural English-speaking arts milieus. Musicians and songwriters such as Bob Dylan, Jim Morrison and Patti Smith were inspired by Rimbaud’s imagistic writing, marked by its visceral intensities and epiphanic electricity, to the point of the hallucinatory. His poems are edgy, vividly illuminating in several senses. Rimbaud, who abandoned writing in his early twenties, could be perverse. When asked why he chose the title, he responded that illuminations were coloured plates or coloured prints. Of course he well knew that his Illuminations were flashes of enlightenment, emotional or metaphysical.

Allowing for the differences in medium, much the same could be said about Albrecht’s mature paintings – so potent in colour, as brilliantly evident in Smythe’s book. Her paintings too evoke the musical. They are also rich in connotations, natural and psychological. Consider just one of Rimbaud’s Illuminations, ‘Fleurs’/’Flowers’, translated by Louise Varese. It could well partner Albrecht’s paintings.

From a golden step,—among silk cords, green

velvets, gray gauzes, and crystal disks that turn

black as bronze in the sun, I see the digitalis opening

on a carpet of silver filigree, of eyes and hair.Yellow gold-pieces strewn over agate, mahogany

columns supporting emerald domes, bouquets of

white satin and delicate sprays of rubies, surround

the water-rose.Like a god with huge blue eyes and limbs of snow,

the sea and sky lure to the marble terraces the throng

of roses, young and strong.

The ‘signature characteristic of Albrecht’s art,’ as I wrote in the Two Rooms Gallery sheet, is its ‘resplendent and charged colour, a poetics of colour. The orchestrations of blues, violets, reds, golden yellows, purples, umbers, black, for instance, give voice to emotion. Colour, effectively, speaks in shapes and forms that may well help us better accommodate the frequent mess of the world beyond.’

Banded Orange 1973

acrylic on canvas

Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū

Albrecht is one of the few genuine colourists in New Zealand art, past and present. A colourist is not just an artist, who uses colour in a particularly skilful or special way, but also one whose paintings are carried by colour, paintings in which colour and its orchestration are the crucial, dynamic, meaning-generating elements. At a conference about twenty years ago I heard the late Jonathan Mane-Wheoki wittily muse on the seeming dominance of black, primarily, and other dark colours in New Zealand art. One could extend that to the often almost total prevalence of black at art gallery openings and among art gallery staff.

With few exceptions, sombre, low-keyed colour – blacks, browns, low-toned greens and ochres – has characterised so much painting in New Zealand. Prominent expatriate New Zealand-born artists were so struck when visiting home – like James Boswell (1906–1971) in 1948 and Douglas MacDiarmid (1922–2020), in 1969 – by the relative absence or infrequency of bright, vibrant, high-keyed colour. This might correlate with a kind of puritan, ‘protestant’ suspicion, even fear, of bright colour, and of red, orange, violet and yellow in particular. Perhaps that allegedly buttoned-up mainstream New Zealand society of much of the twentieth century (vide, Gordon McLauchlan’s The Passionless People of 1976) had a dampening effect on artists’ use of colour. Albrecht’s paintings and collages, as strikingly evident in Smythe’s book, have certainly been an antidote to that. They have helped open eyes and minds to the ways colours can speak.

Back in the mid-1960s the American-born Kurt von Meier was an art history lecturer at Elam School of Fine Arts at the University of Auckland. He had high praise for the work of Albrecht – Onehunga-born, Mt. Roskill Grammar-educated, and one of his former students. He saw her as one of the main hopes for a coming New Zealand art. Sixty years on, in a city – and country – in which the social and cultural shifts have been enormous, it turns out that von Meier was right. In 1965 he wrote:

There is a great mystery occurring to the east of Australia, in a country of green infertility… During the last few years in New Zealand, against all the odds, and after a century and a half of cultural degeneration under the double shadows of a miserable colonialism and a misdirected Calvinism, painting, for no apparent reason, has burst forth with a bright, wonderful challenge to the vapours of vestigial Victorianism.

Albrecht was one of those painters and Smythe’s book shows us why.

Konini Road studio, Titirangi, 1978

Photo: Marti Friedlander

This book is available from BookHub and from bookshops around New Zealand.