Decades in the making, Dr Francis Pound’s artist monograph is forensic in detail and fearsome in ambition – and while the author pointedly eschews biography, he cannot help but articulate a social history of Aotearoa culture in the period 1945–95. The audience for Gordon Walters is therefore broad, but it is powered by the elixir that was modernism and asks the question: has the fair moved on?

Francis Pound passed away in October 2017. The exhibition Gordon Walters: New Vision opened at the Dunedin Public Art Gallery on 11 November that year. It was the first major Walters exhibition since the early 1980s. I was there. Much of the talk that night revolved around Pound. What would Francis think? Would he love this show? What a tragedy that he would not see it.

Within the context of the Aotearoa art world Pound and Walters were and are synonymous. Here, at last, over four hundred and fifty pages we can see why. Gordon Walters has been a rumour for at least three decades. Francis Pound must have been well and truly sick of people, myself included, asking him when it would be published.

But it’s worth the wait. Gordon Walters is an exhilarating read in the way that few art books are. As a body of research there are few comparable artist monographs as absorbing. For some context, two that come to mind are Billy Apple Life/Work by Christina Barton (AUP, 2020) and Dr. Peter Simpson’s two volume monograph on Colin McCahon (There is Only One Direction/Is This the Promised Land?, AUP, 2020).

Pound has always been amongst the most proselytizing of New Zealand art historians. His agenda was to wrench thinking about New Zealand art out of a self-referential and at times suffocatingly introspective focus on the creation of a national voice ‘where the local history of art was read primarily in terms of an unending search for truth to the New Zealand landscape’ and into an engaged dialogue with wider international art trends. He would argue that this was exactly what the artists who interested him most were either actively pursuing or longing to achieve.

This ambitious narrative informed many of his key publications from Frames on the Land (1983), to the Space Between: Pakeha Use of Maori Motifs in Modernist New Zealand Art (1994), Stories we tell ourselves: The Paintings of Richard Killeen (1999) and his penultimate publication The Invention of New Zealand: Art & National Identity 1930-1970 (2009). Pound’s position was consistent: that a true (but not the only) measure of art in Aotearoa was not its ‘outsider’ status but a clearly articulated desire to overcome the tyranny of distance and enter the global discourse.

To this end Pound could have no greater ally than University of Auckland colleague and fellow art historian Leonard Bell to whom the task fell to wrangle, edit and shepherd Pound’s near completed manuscript to publication. I can think of no more potentially fraught challenge, but the proof is in the pudding as they say. Bell provides a sensitive foreword and a succinct, contextualising afterword that addresses the legacies of both Walters and Pound. Bell and Pound met in 1966, the year that Walters burst onto the New Zealand art scene with his ground-breaking exhibition of koru paintings at the New Vision Gallery.

Pound’s instinct to internationalise Walters is aligned closely to Bell’s own examination of the impact of displaced European émigrés in mid 20th century Aotearoa, on and the modernist teachings with which those artists, architects and writers then fertilised provincial New Zealand. Bell’s Strangers Arrive: Émigrés and the Arts in New Zealand 1930–1980 (AUP, 2017) illuminates some of the creative alliances Walters formed with this influential cohort, most notably the Dutch artist and one-man ginger group Theo Schoon (1915–1985).

The early chapters of Gordon Walters is a who’s who of European mid-century modernist influences. Pound reveals that, from the mid 1940s, frequently at the urging of Schoon, Walters was something of an artistic glove-puppet, sliding into the styles and concepts of Paul Klee, Yves Tunguy, various Surrealists and Cubists and ultimately the Dutch abstract pioneer Piet Mondrian, in his search for a Yoda – a figure to guide him in his journey away from the all-encompassing emptied landscapes that were then the only game in town and into the ‘force’ of pure abstraction. The early chapters provide detailed accounts of the encounters and catalysts that enabled Walters to untether from the former and cleave to the latter. The first was a visit, at the invitation of Schoon, to inspect the Māori Cave art located in South Canterbury, and this was to prove decisive in Walters entire artistic direction for the next five decades. The ‘rock drawings came as a revelation for Walters,’ Pound writes on the artist’s first site visit to the limestone caves, one ‘that instantly changed his art, and permanently affected him’.

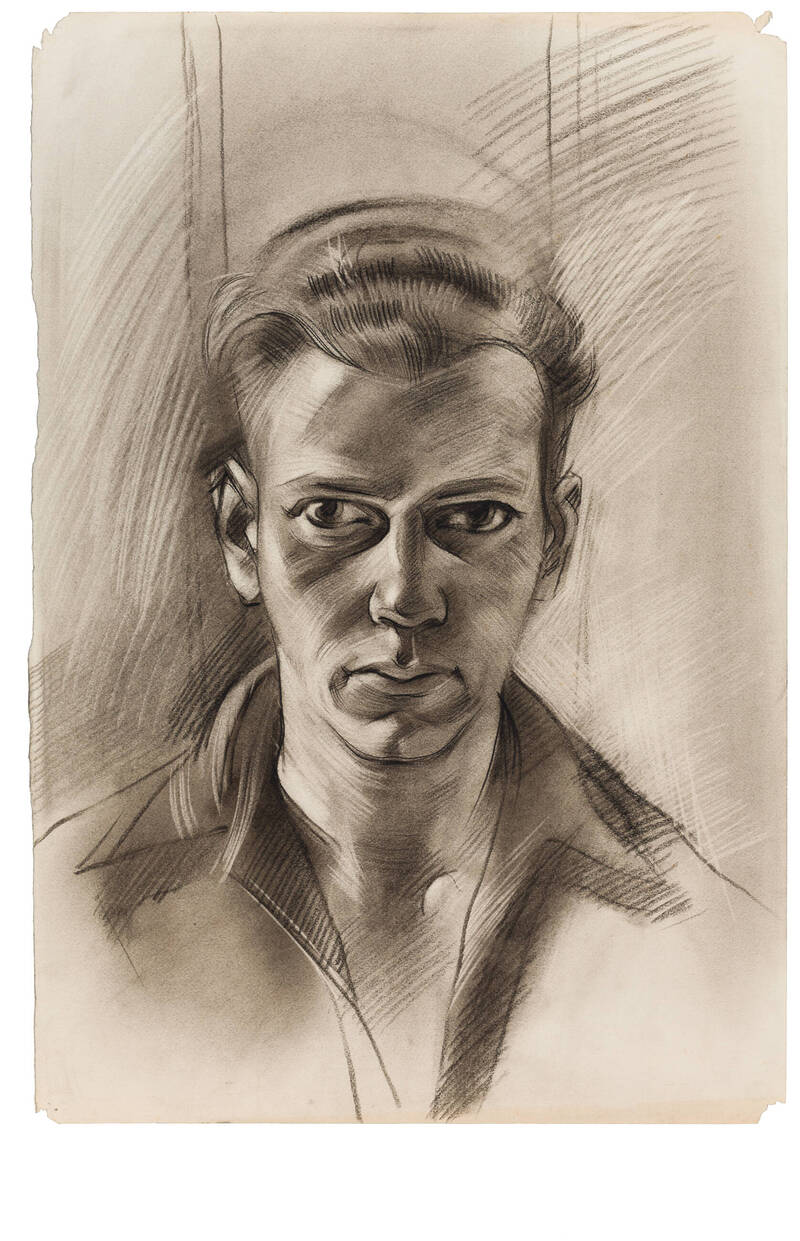

Gordon Walters, Untitled Self Portrait, c. 1942-43, charcoal, 565 x 380 mm

Dunedin Public Art Gallery Loan Collection. Courtesy of the Walters Estate

The chapter ‘The Journey to Europe’ is a revelation. Via direct discourse with Walters during his lifetime and his forensic research into the exhibitions and individual works Walters encountered in 1950/51, Pound assembles a cogent argument for Walters’ decision to go into internal exile for nearly two decades of creative purdah, during which he laid the groundwork for his mature work of the 1960s. His artistic OE was an exciting time for Walters, by then in his early thirties. In post-war Europe he could view works previously only available to him in the smattering of art magazines that made it to Aotearoa in the 40s, or through the accounts of displaced émigrés such as Schoon. For Walters this experience was life-changing:

Having finally reached Europe, in the very moment of being among works so long admired… there came an implacable realisation, a kind of bleak epiphany. ‘For the first time I felt the full impact of N.Z.’s insularity and isolation from European culture’ … In Europe he had become possessed by what would be one of the most enduring purposes of his life: to make his art participate in the international modernist revolution, despite the almost insuperable barriers he knew would be put in his way upon his return.

In post-war Aotearoa, abstraction was ‘detested and mocked’. ‘As soon as you abstract, you falsify, and give lie to life,’ wrote A.R.D. Fairburn. ‘Hence the death-corpse-stinking falseness and utter dishonesty of Picasso.’ On his return, Walters, effectively went into hiding, not exhibiting until the New Vision exhibition in 1966. During that period of near solitary confinement, barring the odd exchange with figures such as Schoon, Walters initiated a series of artistic lab experiments as he sought to synthesise the pictorial language of modernism with visible signs of Aotearoa including motifs from Māori and Polynesian culture. Pound describes this seventeen-year period as one of an ‘unending fertility of invention’. It was ‘Walters’ experience of an ‘elsewhere’ that provoked and made possible his staging of the local.’

This decade and a half period of internal exile forms the heart of Gordon Walters. Pound examines the pictorial influence of the Māori cave art and Walters’ exacting process of image making via collage, sketches, false starts and incremental gains as a composer might notate a symphony. In the mid 50s the koru motif emerged in a series of gouache on paper riffs and sketches, but a further decade of experimentation, controlled tests and refinements were undertaken before the koru works, as we understand them, were ready to exhibit.

In the 50s Walters pursued a singular period of research that powered almost all of the work that followed the 1966 exhibition – with detours into the art of schizophrenic patient Rolfe Hattaway (again, material passed to Walters by Schoon), interlocking forms and his now-famous En Abyme works with their self-replicating internal structures. This was also the decade when Walters took a job at the Government Printer as a layout artist and designer. From 1957n until 1966 he was senior artist in charge of the art department. It was not until 1976, when Walters was fifty-seven, that he became a full-time painter.

Walters always had a bet each way in describing the birth of his Koru works. On the one hand he saw the koru as an exercise in exploring ‘dynamic relations’ in a formal modernist sense; on the other he sought to locate his modernism in a space and a place that evinced his claim that he was ‘not a European’. In the 1990s this approach opened Walters up to accusations of cultural appropriation, but the impulse to join or amalgamate his two great loves has made him curiously and continuously relevant. Despite modernism’s slightly greying museum status in the 21st century, contemporary artists such as Michael Parekowhai and Ayesha Green return to Walters for source material. Quite clearly for New Zealand observers Walters’ Koru works are not devoid of the embedded cultural content from which he tried to distance himself. That is their ongoing dilemma and allure.

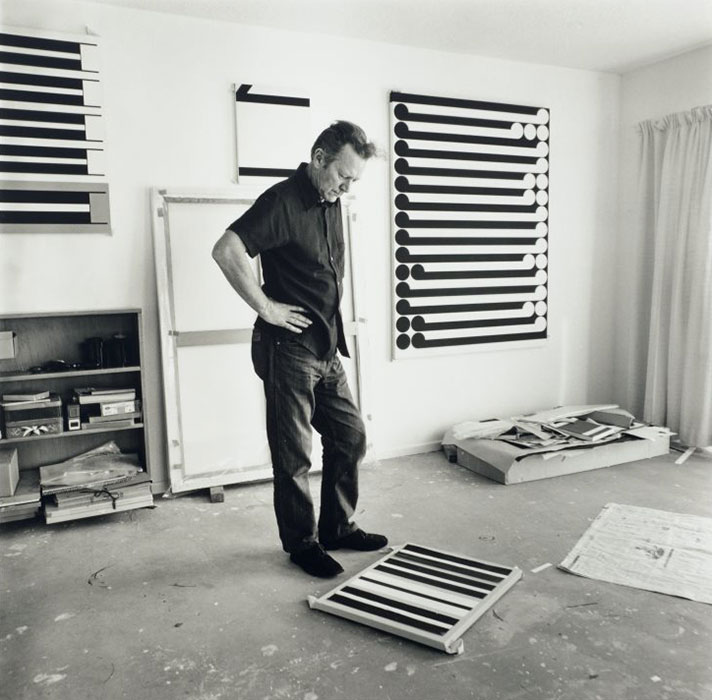

Marti Friedlander, Gordon Walters in his Studio, Christchurch, 1978, black-and-white photograph. Courtesy of the Gerrard and Marti Friedlander Charitable Trust

Pound makes a cogent case for the dedication and sincerity of Walters’ research and experimentation in the late 50s and early 60s. Almost every preparatory gouache of this period is treated to analysis, as he describes Walters balancing act, simultaneously seeking to align and distance himself from obvious references to Māori motifs, and his ‘agonising eight-year effort to achieve a form sufficiently sharpened and polished to live up to the structural promise of those initial studies of 1956.’

The artist, Pound reports was in flow, moving

further from his Māori sources, yet still pondering on their underlying structural principles. Eliminating superfluities… in a process of repeated trials… he will finally attain the individuality of style, the accuracy of expression and the economy of form he seeks. Only then… when all the labour is concealed, as if the painting had miraculously come to him whole and at once, unbidden and increate, will he find himself ready at last to show.

The first exhibition of the Koru works – March 1966 at New Vision Gallery – was attended by two young art students, Francis Pound and Len Bell. Both the content of the works and their startling, austere abstraction swam against a strong cultural riptide. As Pound notes the prevailing atmosphere had not changed much since Fairburn’s ‘death-corpse’ comments. Colin McCahon’s entry, a few years earlier, into the Hays Art Prize was greeted with a ‘nationwide outpouring of scorn’. The official position towards Māori cultural expression of any form was articulated in 1966 by no less an authority than Stewart Maclennan, director of the National Art Gallery, in An Encyclopedia of New Zealand, published by Walter’s own employer, the Government Printer: ‘No Maori artist of stature has yet arrived. The process of integration has isolated the Maori of today from the living meaning of the arts of his forefathers, and his culture must, from now on, be one with that of his European neighbours.’

Initial reactions to the Koru works did not respond to the Indigenous reference points but more to their radical abstraction: the New Zealand Herald review’s headline read, ‘Between Op Art and Geometry’.

In 1966 Walters was wary of naming the Koru works with clearly articulated Māori titles. But by their next significant exhibition outing in 1968, again at New Vision Gallery, Walters had jettisoned such reticence and the works’ latent imagery and titles coalesce. Pound contends that until this point Māori motifs such as kōwhaiwhai and the koru were encountered within the Pākehā world shorn from any cultural role or associated symbolism but as decoration, found on stamps, postcards or teacups. Perhaps Walters’ most enduring legacy was his deployment of these forms – abstracted, refined via a long term programme of visual thinking – into the arts discourse, where they have remained to this day.

One of the key achievements of Gordon Walters is how Pound balances the different beats of Walters’ six-decade career. In his final decade and a half Walters, although not completely leaving the koru behind, delved again into his 1950s playbook to produce a series of abstract works that clearly intrigued and delighted Pound. There is much to be discovered on the artist’s journey in the later chapters, and Pound is assiduous in the attention he places on the later work and their genesis within wider Pacific sources such as tapa.

At the very end we return to Bauhaus-based abstraction with the Transparency works, suggesting the influence of modernist legends Joseph Albers, Paul Klee and Braque, as well as Auguste Herbin and Giuseppe Capogrossi. Pound’s detective work in this area highlight both Walters’ breadth of thinking, even in his most isolated moments, and the author’s view that these are essential entry points into Walters’ overall project. On both counts these are convincing.

It falls on Len Bell to conclude Pound’s fascinating chronicle. At over 450 pages, 420 plus illustrations and a blizzard of footnotes and quotes, Gordon Walters is a Wunderkammer book. ‘For Francis,’ Bell writes, ‘books were as much imagined as real. In fundamental ways his writing was always in process, to be continued’. Gordon Walters is a triumph of that imagination, as well the collective editorial skills of Bell and the AUP team. Kudos also to Inhouse design who have created one of the most handsome art books produced in Aotearoa.

Walters’ north star, Modernism, no longer illuminates the contemporary art world. But Gordon Walters reminds us that the ‘dynamic relations’ of the modernist lens, and the Indigenous visual culture which he dedicated his life to exploring, remain vital forces in Aotearoa.

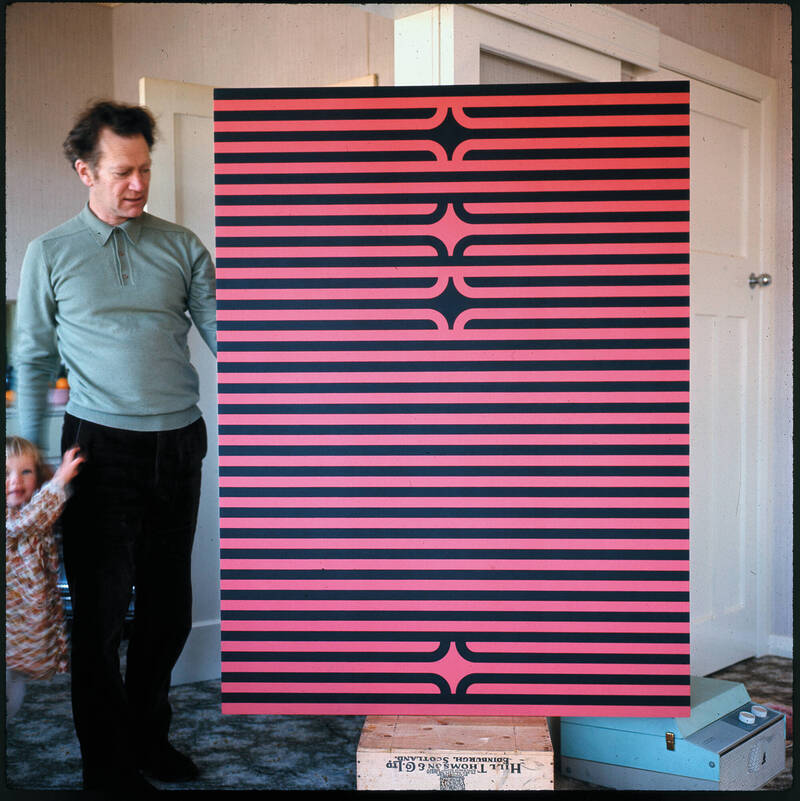

Walters with Black and Red, 1970, PVA and acrylic on canvas, 1527 x 1143 mm

Walters Estate, Auckland