Like so many people, I remember exactly where I was in 1995 when I heard about the tragedy at Cave Creek, where 13 young people and a DOC worker lost their lives on a collapsed viewing platform. I was standing in the stairwell of the Auckland University Student’s Association with my colleagues at bFM, having a cigarette break, when one of them told me. Even now I remember the gut-punching shock of it.

Only four students escaped alive. Six years later I interviewed one of them for a documentary, and he talked about how he had traumatic amnesia (or what I now know, thanks to Golden Days, is called ‘localised dissociative amnesia’). His memory had erased not only the terrible event, but the previous thirty minutes, a fact for which he was ultimately grateful. The last thing he remembered was climbing over a wooden stile into a field.

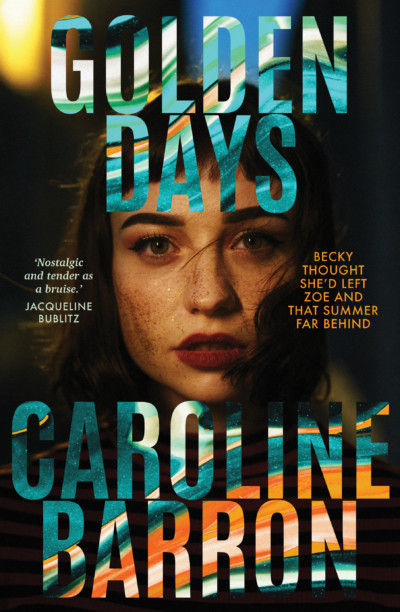

Cave Creek features in Caroline Barron’s propulsive debut novel Golden Days, her second book after the 2020 memoir Ripiro Beach. The narrator returns to the disaster again and again – remembering when it happens and dreaming about being on the platform, falling. The creek’s cave itself becomes a metaphor, as do other caves, a repeating motif about the truths we bury deep inside ourselves and the need for ‘daylighting’ – emerging into the light.

There is a more literal parallel, as becomes apparent in the second half of the book but suffice to say this is a book about memory and trauma, and the exploration of these themes is the book’s heart and major strength.

Narrator Rebecca (Bec, Becky) has discovered her husband is having an affair and has fallen into a trap of drinking away her feelings. Her saintly friend Meg (more on her later) arrives to help her process her grief in more healthy ways; as Rebecca does this, she is cast back seventeen years to 1995, the year she met Zoe, a charismatic manic-pixie-dream-girl character, and a summer that changes her life forever. Zoe is an artist, a party girl, an alluring counterpoint to Rebecca’s safe and loving upbringing. With Zoe, Rebecca feels all the heady possibilities of what life has to offer, and in the process believes she is discovering her best, most creative self.

Rebecca is a lover of literature – she is named after the Daphne Du Maurier novel, though she is more of a second Mrs de Winter than a first – and Barron cleverly weaves books and their tropes through Golden Days. It’s no coincidence that Becky is reading The Secret History when she first meets Zoe, who sits down on the bus next to her and pronounces ‘Tartt’ a genius (not ‘Donna Tartt’ – it’s fair to say Zoe is more annoying and pretentious than alluring to the adult reader). Rebecca is drawn to Zoe the way Richard Papen is drawn to the clique of elite Classic students who lead him into trouble. Like Golden Days, that novel is narrated from a point in the future by an adult looking back with a mix of nostalgia and horror.

In the ‘90s I worked in a bookshop in London, and The Secret History was hot property. The other book that is seared in my memory from that time is The Celestine Prophecy by James Redfield, but not for such positive reasons. It seemed that every tenth person came into the shop that summer to buy that bloody book. My colleagues and I despaired that so many good books were languishing on the shelves while this hyped-up, pseudo-spiritual claptrap stole all the attention. The thing is none of us had actually read The Celestine Prophecy. We just knew it was bad. We were utter snobs.

Zoe and Rebecca read it. ‘Over time,’ recalls Becky, ‘we devoured the nine insights, tried to retrofit them to our own experiences’. This is what I did too, reading the nine insights and finding Zoe and Becky’s relationship throughout. The two women seek out ‘meaningful coincidence’ and ‘subtle energy’, get caught up in ‘control drama’ and aim for ‘conscious evolution’. The Celestine Prophecy provides a framework for their dramatic arc, but at least twenty-first-century Becky has a sense of humour about it: ‘Two steps forward, one cereal-box-philosophy step back.’

There is much to admire in this novel. Auckland of the mid-90s is brought to life with vibrant specificity, a fact that makes me realise how rare such a thing is. Reading it is like being chucked into the Pavement Party People page – all skinny young women with hair bunches, floor-dragging skirts, mesh tops and bare midriffs, angel wings and glitter. There is no vague fudging of band names and locations that you might get in other novels: it’s all there, from the music (Head Like a Hole, Pauly Fuemana, Bic Runga’s Drive) to the fashion labels (Carhartt, Karen Walker, Zambesi) to the make-up (brown lipliner, plucked eyebrows and that chalk-dry dark Poppy lipstick we all wore). Even real-life characters from High Street nightclubs The Box and Cause Celebre make it in there, as do the grungier bars: Squid, Deschlers, Poppa Jacks, and the Dragon Bar – all places I frequented with alarming regularity, and one where I had my drink spiked (I escaped any lasting harm thanks to my friends).

Barron expertly portrays the particular melancholy of nostalgia, when we look at our younger selves (‘optimistic, expectant, unscathed’), and feel a hopeless sort of yearning. Yet in among the clouds of nostalgia, the golden days, are some uncomfortable truths about Auckland nightlife in the ‘90s from which Barron doesn’t flinch. Sexual harassment and exploitation were rife, as was downright sexual assault. So many young women were not as lucky as I was. Rebecca has a narrow escape (in another cave) – in a scene reminiscent of the Dionysian frenzy in The Secret History – that haunts her for years. It’s a turning point in Zoe and Rebecca’s friendship that shapes all that is to come.

At one point Meg and Rebecca look at each other and marvel: ‘Shit… We let so much slide back then.’ We can only hope that, in the wake of #metoo, our daughters and nieces will have the strength, be emboldened, to call that shit out.

While the ‘90s scenes are familiar to me, the people Rebecca and Meg (and Zoe) become are not. Young Meg declares her life intentions early on, seeing security and being ‘able to go on overseas trips and shop at Karen Walker’ as the key to happiness; she represents the material comfort that James Redfield is urging Becky and Zoe to react against and leave behind.

But after the tragedy of that summer, Becky follows that path anyway, looking for safety in marriage to reliable Jono, and in the process accumulates all the trappings of a wealthy middle-class lifestyle: a plumbing business, designer outfits, furniture and glassware (she doesn’t just drop her clothes on a chair but on an Eames chair; her wine glasses are ‘rows of Riedel for red, white and bubbles’), and friends who get Botox at 37. She’s about as far from bohemian as you can get. Something has to give; we learn that Rebecca has subconsciously rejected her life.

If we’re lucky, we all experience friendships that burn brightly; I had one at 19, the first where we chose each other rather than drifting together by being schoolmates or flatmates. They’re as giddy as romantic love. The central friendship in this story is Becky and Zoe, but the unspoken true relationship of the novel, for this reader, is between Becky and the solid, dependable Meg.

It made me think (of all things) of the Disney movie Frozen, where Anna’s frozen heart can only be thawed by an act of true love – and no, it turns out, not true love’s kiss, but an act of sacrifice for her own sister. When Rebecca says, ‘If [Jono] of all people can no longer love me, who will?’ Meg is right there, under her nose, making sacrifices and forgiving Becky’s neglect. Why can’t friendships between women not be valued as highly as romantic and marital pairings? Those relationships often last much longer. Towards the end of the novel, when Becky says (quoting George Herbert and the book’s epigraph), ‘The best mirror is an old friend’, I can’t help feel that she is still chasing something shiny and unobtainable, and she is looking in the wrong mirror.

Barron’s writing is thoughtful, vigorous and free from cliché. She employs frequent and inventive metaphors. Seeing an artwork Becky was once invested in feels, she says, ‘like finding a copy of a favourite childhood book in a second-hand shop, only to open the cover and see your name printed wonkily in the front.’ At one point she tells someone she is fine, but admits to herself that this isn’t true: ‘I’m a woman on top of a cliff, about to fall.’ I can’t help thinking of poor Bunny in The Secret History, or a desperate Mrs de Winter contemplating ending it all.

Sometimes, however, the metaphors and similes become laboured and too complicated (or downright silly) for their own good, ejecting readers from the moment as we struggle to picture what she is describing: ‘He had a wide smile with a dimple, like a single dip of bubble wrap in reverse, on each cheek.’ Or: ‘My voice feels rushed, like it’s hissing out of an air-release valve on a pool floaty.’ There’s a particularly egregious example, in the most important emotional moment of the book, where a long and convoluted description of a metaphorical Coke can made me laugh out loud instead of feeling Rebecca’s pain.

Also undermining the moment, especially in the first half of the book, is the constant intrusion of 2013 Rebecca, interpreting and commenting on the characters and events of the past rather than let the reader experience them. Scenes lose power and momentum when the narrator keeps explaining what you have just seen. Rebecca tells us:

Zoe would ask for money, or to take the car out, and [her mother] Trish would say no, then Zoe would coax and cajole, and within minutes Trish would flip-flop and no became yes.

At this point, we see the manipulative power Zoe has over her mother. Becky’s next-line summary – ‘She just couldn’t stand up to her daughter’ – is unnecessary.

Even in the present-day story, Becky can’t help swerving away from a moment. In one important scene, Becky’s first encounter with Zoe in seventeen years, she pauses to comment about the pros and cons of Pākehā learning te reo Māori and using it in formal settings, either at the expense of ‘urbanised, language-lost Māori’ or as ‘one way Pākehā can support tikanga Māori.’ It’s a valid discussion but one completely out of place in the moment of the scene, and feels much more 2023 than 2013, when the novel is set.

Becky’s parents act as oracles, popping up to foreshadow with platitudes and snippets of wisdom (‘Mum’s Pocket Parenting Tips’, as Becky labels them – at least acknowledging their artifice) but they are never really developed as flesh-and-blood people. One idea introduced by her father ripples through the whole novel, with a question that comes up again and again as Becky sorts through her memories and confronts the truth: can more than one thing be true at once? The question is a central theme and is poked and prodded in a satisfying way to the very end: as in Du Maurier’s Rebecca, a crime is examined in a new light.

Perhaps the role of the unreliable narrator is to intrude constantly to manipulate the reader’s own perception of events. And in a story about truth and memory, it’s not out of the question that the narrator would interrogate her own memories: ‘We all leave out or forget sentences… in service of the greater narrative,’ says present-day Becky, ‘…harmless white lies that reinforce the story we’re trying to tell about ourselves’.

There’s a moving scene at Piha, where many of the themes and metaphors of the book converge when Becky takes us on a walk through a cave and remembers visiting it with her brother, Chris. This is where she explains the origins of the ‘daylighting’ metaphor, and I think again – and wonder if Barron did too – about Cave Creek and another survivor who was not so lucky to lose his memory. He confessed that he and some of the other students had deliberately shaken the platform just before it fell, and he had been burdened with the guilt ever since. He didn’t tell anyone for ten years, including the police, because he thought he might be held responsible. It took a huge mental toll, but when he finally confessed, nobody blamed him; the platform should have been built to withstand simple teenage horseplay.

In Golden Days, the key setting of West Coast beaches – scene of memories both golden and painful for Becky and her family – is lovingly, poignantly brought to life. I couldn’t help think of the recent devastation to the communities there, and what will become of it in the future now that the threat of climate change – not anywhere in the young minds of the ‘90s – is so real. This is an Auckland book in many ways, and anyone who grew up there, came of age there in that heady decade, or who lives there now will find much to connect with. That it took an Australian publisher to see its value seems ironic.