In 2005, while I was living in California with my partner, raising our two-year old son up a backstreet in the Glassell Park hills of northeast Los Angeles, I wandered the open hillsides with my boy in a backpack. We looked at plants and hoped we wouldn’t stand on snakes. Every now and then if we were very lucky, we would catch a glimpse of a coyote mother with her pups, slinking into a gully filled with wild walnut trees and treacherous vines of poison oak that could make your whole body come up with itchy, seeping blisters if you brushed against it.

When Hurricane Katrina hit the Louisiana coast in August of that year, it was a scary time to be in America. Some of New Orleans’ levees broke, flooding eighty per cent of the city. Two thousand people died and a million were displaced. Back in Glassell Park, I became a much more anxious mother. I now knew I wasn’t living in a country that could (or would) protect my family for me. I bought a lockable plastic chest, stuck it in my back yard and filled it with bottles of water and cans of beans. I planted a rather parched vegetable garden, and as we walked the hillsides, I found my eyes drawn to plants I could call on if some kind of catastrophe struck. I kept noticing fat, ripe grain growing on those grassy hills, ears of which I brought home in bunches and contemplated winnowing, although I didn’t know how. What I had first interpreted as wheat, I later discovered was actually barley, seeds of which had been scattered on those hillsides in the 1930s in an attempt to prevent erosion.

It was this fantasy of self-reliance amid cataclysm that led me to produce LA Botanical, a series of wet-plate photographs, that I self-published as a guidebook of sorts to functional plants introduced to LA as medicines, foods, fuels and entheogens that had managed to survive and even thrive in that desert city. (LSA, a plate from this series, appears in Flora.)

As someone raised on a farm in rural Aotearoa, something that struck me about life in Los Angeles was a generalised lack of ability to differentiate plants. Many of my grad-school-educated friends struggled to distinguish an oak from a walnut. Some didn’t know what common vegetables looked like outside the freezer aisle. There was a layer of information in the landscape that was unavailable to them, information that many were actively trying to retrieve. LA Botanical was conceived as a remedy for that peculiar form of oblivion, and a salve to the anxiety that can accompany such incapacity.

Though they have been working from a vastly broader, deeper archive than I, drawing from Te Papa’s trove of botanical materials in the Māori art, botany, history, Pacific cultures, decorative arts, design and photography collections, Flora’s editors have expressed similar motivations for making this book. In their opening essay they write:

Despite plants being so intertwined with human history and our daily lives, many of us struggle to name, describe, or in fact even notice, the plant species around us, a phenomenon known as plant blindness. Fortunately, this is curable. The cure involves promoting the uniqueness and wonders of the plant world and creating emotional connections with species, for example, those that mark seasonal events such as the arrival of spring, or important events in our lives such as weddings and periods of mourning.

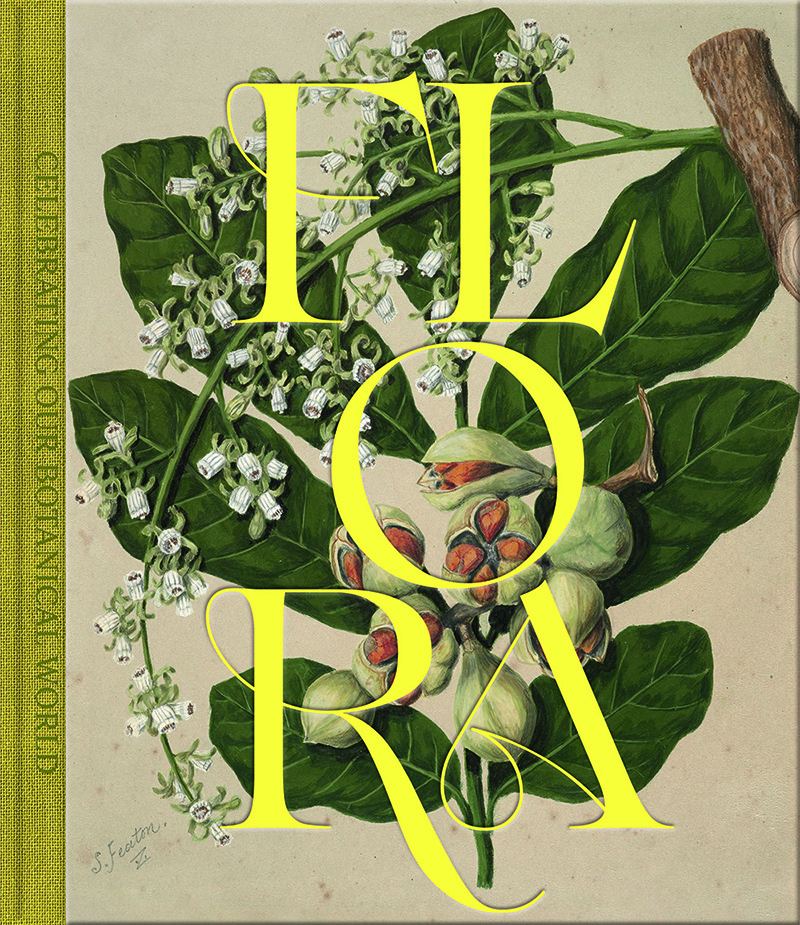

To the affliction of plant blindness, Flora ‘is designed to play its part as an antidote’. What magnificent medicine it is, with over four hundred images and artifacts. In the essay ‘Ko Papatūānuku’, Jessica Hutchings describes the ‘taonga and the flora representations in the Te Papa collection and in this book’ as ‘our love letters to and our acknowledgements of the children of Tāne and their desire to clothe and protect their Mother’. In an era of relentless cultural belt-tightening, stifling pragmatism and shocking violence, this book proposes beauty, empathy, seduction, love and caring as cure.

Weighing in at two and a half kilograms, Flora is obviously a labour of love and repository for the pet obsessions of its five editors and the many members of Te Papa’s team who contributed their scholarship through framing texts. It is a great doorstop of a book stacked to the brim with images and objects, not so much thematically curated as laid out in pairings that resemble each other in colour, texture or shape. Juxtapositions abound, as objects and images are brought into relationship with each other through the logic of general appearance.

Many of the artifacts featured are finely crafted, vernacular, decorative and feminine. Women feature large as researchers, makers, and subjects, perhaps because, as Rebecca Rice explains in her essay ‘Flora’s Daughters’, a long-held patriarchal association between flowers and ornamental female bodies has meant that women were not prohibited from exploring botany as subject matter.

Design c. 1950. A Lois White (1903–1984), Aotearoa New Zealand. Watercolour, 311 × 247 mm; 2002-0031-2, purchased 2002. Harakeke, flax, Phormium tenax; unidentified flowering plants.

Like its name, Flora feels a little old-fashioned in all the best ways. Its pleasures mimic those of the dusty museum shelves of yore. There are none of the snazzy trappings I associate with contemporary museum displays: the heartstring tugging immersive environments, the surround sound and interactive digitality of the new museology. No one is asking me to sit in a lurching room while being splattered with virtual lava. There isn’t even an associated website. Instead, the book offers a window into the vast collection of an encyclopaedic museum. That’s a complicated proposition nowadays, as museologists have been grappling for several decades with an urgent obligation to decolonise these inherently colonial institutions filled with pillaged artifacts.

Given Te Papa’s origin story, these tensions couldn’t be more explicit. Afterall, their botanical collections ‘date back to 1865 when Te Papa’s predecessor, The Colonial Museum was founded’. Tristram Hunt, current director of the Victoria & Albert Museum – a veritable temple to colonial acquisitiveness – has said that in ‘Britain’s colonies and spheres of influence, the practice of collecting was intimately tied to the dominating psychology of colonialism… Our aim should be to detach the universal, encyclopaedic museum from its colonial preconditions and reimagine it as a new medium for multicultural understanding’.

While Flora is encyclopaedic, it certainly doesn’t adhere to a rigid, narrowly framed hierarchy built on colonialism, capitalism or patriarchy. Its essayists may be a rongoā practitioner, an artist, a gardener, an art historian, and specialists in botany, Matauranga Māori and Pacific Studies. They give generously of their professional insights and bring deep personal and familial connections to the work of reigniting our empathy, curiosity and love of plants.

The essays offer multiple intellectual portals into the collection, their brevity and condensed intensity making them challenging and accessible in equal measure. While the wicked problems of climate change, deforestation and plummeting biodiversity are certainly explored, they don’t overwhelm the book’s sensual pleasures to render us passive or numb. Instead, readers are given privileged access to treasured family narratives, demanding research and specialised bodies of knowledge that hint at deeper reservoirs to plumb.

Each text is printed on precisely two leaves of brightly coloured paper – purple, pink, yellow, aqua, orange, green – that lace through this big fat book like layers of a delicious rainbow cake. All the parts combine to form a complicated picture of the earth’s living skin. The overall effect is kaleidoscopic, fractal or… dare I say divaricate?

Because flowers are pretty and ornamental, they can be written off as superficial subject matter, but flowers are the way that plants seduce other species in order to reproduce. Te Papa’s resident botany curator Carlos Lehnebach shares his passion – in ‘Not Your Standard Wallflower’ – for the sexually deceptive trickery of orchids, which lure male insects with the flowers that have evolved feminine insect forms and seductive quasi-pheromonal scents.

In Leon Perry’s marvellously nerdy essay ‘Endemic and Unfussy’, we learn that ‘New Zealand could claim to be the liverwort “capital of the world”’; that our flowers are largely sexually ‘unfussy’; and that one ‘of the most remarkable features of New Zealand’s woody flora is the “divaricate” growth form, characterised by having small leaves usually less than 2 centimetres long on branches that are often flexuous and spread at wide angles, forming an interlacing, cage-like architecture’.

Other essays discuss cultural practices across our ocean region. In ‘Goths of the Pacific’, Isaac Te Awa contemplates the ways Māori adjusted to a land that was so much colder and less abundant than the tropical islands they left behind: ‘the plants that provided the vibrant dyes and bloom of colour for garments common to other islands did not survive here’. Nathanial Lennon Rigler Siguenza, in ‘Things That Decay’, conjures up a magical building that rose and fell at his ancestral home in Guam in the years before he was born – a wedding venue with walls built entirely of woven pandanus:

In the early hours of the morning before the wedding, my uncles trudged into the dense jungle to gather pandanus. They bundled the leaves together and packed them tightly into a convoy of trucks that traversed the muddy roads back to my grandparents’ home.

Still before sunrise, the dozens of aunties who came to receive the pandanus organised themselves into assembly lines. Weaving the leaves together, they constructed the walls of the entire wedding venue large enough to fit the hundreds of relatives attending. In the Pacific, a wall is not a wall. It’s a gift from the flora of the Island, from the aunties who weave, from the ancestors who taught the aunties to weave, and, especially, it is a gift of the woven social fabric that accomplishes this level of work in a single morning.

Having long ago rotted back into the soil, this ephemeral building still lives on in memories inherited from its makers. Through it, Siguenza identifies impermanence is an intrinsic quality of the sacred for Pacific people, while the knowledge required to construct that building is ageless, passed on through generations as cultural lifeblood.

As the planet pivots from an epoch of extraordinary abundance fuelled by the buried and compressed corpses of ancient flora, we find ourselves staring into the abyss that is a desert devoid of plants. I’m reminded of Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower, an attempt by that most prescient of authors to elicit empathy and to remedy plant blindness. To move forward toward any kind of future, we must look backwards and we must collect seeds.

Amid Flora’s images of abundance, I found myself searching for clues to lives sustained in the relative scarcity of cool, dark, forested precolonial Aotearoa – like the Pungapunga made from pollen gathered from the flowers of the raupō plant, kneaded into dough and baked into cakes described by William Colenso as tasting a little like gingerbread. Perhaps my favourite artifact in this book isn’t actually a plant at all, although it was once believed to be so. Āwheto are larvae of the Aoraia dinodes moth, infected by the parasitic fungus Ophiocordyceps robertsii, who hijack the grubs’ bodies for their own reproductive ends. These zombie grubs were used by Māori to make ‘an almost black pigment called ngārahu’ used in the art of tā moko.

Āwheto. Dried specimens, Aotearoa New Zealand 200 × 8 mm each (approx.) ME024190, purchased 2015. Vegetable caterpillar (fungus), Ophiocordyceps robertsii

Photosynthesis is the only means by which living things can harness the energy of the sun to continue living, so there is nothing deeper or more intrinsic than our relationship with plants. ‘We need our plant children,’ Jessica Huchings writes. ‘We all breathe the air they provide and eat the food they offer’. In this age of extinction, when botanical treasures are teetering on the edge or falling into oblivion, we learn about one species pulled back from that brink. A still from Raewyn Atkinson’s video I too am in Paradise points to a deeper story that has been unfolding since 2015, when an envelope containing seeds was recovered from the abandoned hut of amateur naturalist deep in the Ruakituri valley East of Te Urewera. That envelope had sat undisturbed for perhaps seventy years. In it were seeds of Ngutukaka Ma, or white Kaka beak, a species considered extinct since the 1950s.

From around eighty seeds, biologists were able to propagate two seedlings. These have grown to produce many more plants that have been returned to Ngai Kohatu of Te Reinga, who are propagating and caring for them and on whose cliffsides the wild Ngutukaka Ma will being reborn.

I TOO AM IN PARADISE II, 2018

Raewyn Atkinson (1955–), Aotearoa New Zealand. Moving image (time-lapse video)

CA000888/052/0001, purchased 2020

Ngutukākā mā, white kākā beak, Clianthus sp.

In the whakataukī that opens this book, Meri Ngāroto asks:

Pull out the central shoot of the flax, where will the bellbird sing to me?

The watercolour design by A. Lois White pictured earlier in this review is a visual poem to the abundance of the ngahere and the earthly gifts provided by harakeke. By some fortuitous twist of fate, I have spent the last week learning how to turn harakeke into paper alongside Māori leaders determined to restore this exceptionally useful taonga plant to the centre of hapū life, where its deep roots strong fibres can hold whenua, awa and tangata together.

This work has been a tactile reminder: to touch the page of a book is to touch the body of a vegetal entity that once lived. Every one of the four hundred and two images in this book is a love letter and a testament to human life entangled with the lives of plants. Te Papa’s large curatorial team, who spend their days steeped in this glorious collection, have dug deep to find those stories, and to share them with us. Open Flora on any page and you will be drawn into and immersed in those stories. What pleasure, what joy, what richness, what abundance, what love.

This book is available from BookHub and from bookshops around New Zealand.