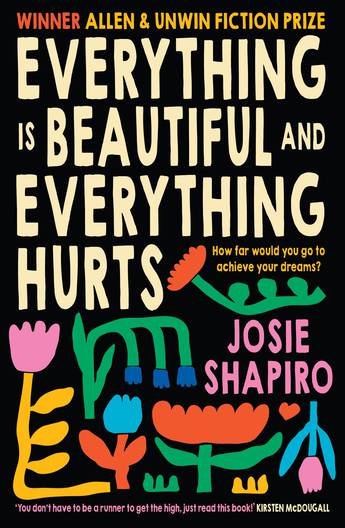

Josie Shapiro’s debut novel, Everything is Beautiful and Everything Hurts was the winner of the inaugural Allen & Unwin Commercial Fiction prize. It is also a quietly uplifting and wonderfully absorbing story of vulnerability and endurance. Its title an apt play on a famous line from Kurt Vonnegut’s 1968 novel Slaughterhouse-Five (‘Everything was beautiful, and nothing hurts’), the novel is the story of Michelle – AKA Mickey – Bloom, a young woman and long-distance runner trying to find that balance between beauty and pain, peace and ambition.

Our narrator grows up near the beach in Ngāmotu with her mother, Bonnie, a woman of ‘patience and quiet love’ and her three older siblings. At home Mickey feels lost as the youngest child, ‘caught in the family’s slipstream, pulled to Helen’s jazz dance class and Zach’s football practice and Kent’s weekly library visits for more and more books’. Her negligent father, Teddy, lives in Auckland with his new wife and barely visits; he is ‘not there to direct me one way or another.’ As an adult she realises that over the years ‘there had been too many birthday presents “from your father” that I knew my mother had wrapped herself’.

At school, reading is a struggle for Mickey: books are ‘full of nonsensical code I couldn’t understand’. She is bullied by kids who call her ‘dwarf’, her great triumph a childhood relay when she proved herself, the ‘midget, the shrimp, the little Bloom taking out the race’. But her father mocks any Olympic ambitions, and Mickey absorbs the criticism of her peers:

I was short, miniscule – at fifteen, no bigger than many children much younger than me. So I wasn’t only useless academically. I was too short for basketball, unwanted for any netball team. My thrilling win at the community athletics eight-and-a-half years earlier was nothing more than a whisper, a colour faded to a pale hue. It seemed that nothing special ever happened to me, and nothing ever would.

The novel is split into two parts, with the chapters in each alternating between a marathon in the present and Mickey’s past. The thrill of the race we are running with Mickey only grows in intensity after we get another glimpse into her past every other chapter. The first part covers episodes from Mickey’s childhood, including that first successful relay race and the intoxicating feeling of defying expectations, ‘winning when everyone expected I would lose.’ An obsession with running emerges when she watches the female runners in the Sydney marathon on television, transfixed by the way the women look ‘as though they were flying’.

Shapiro perfectly articulates the chaos and confusion of being a teenager, thrust into new, adult interactions with ‘a churning of feelings, nothing explicit and yet everything all at once.’ Bullied all her life for being ‘too short, too fat, too female’, Mickey still feels inadequate at Birchfield Athletics, ‘I knew none of them. No one looked at me, and I bit my nail in disappointment. I’d imagined this might be the place where I’d fit in.’ Athletics offers both empowerment and confinement, a rigid set of expectations. From the coach’s advice to Mickey and the other female teenage runners, she learns: ‘Lighter meant faster. Be as light as possible. I would lose weight until my body almost lifted from the ground.’

Mickey loves her family – ‘the noise and the mess of four children, it felt like a home’ – and misses her older siblings when they move away to university. But as running becomes a passion rather than a pastime, her family struggle to understand her deep need to run. Her parents forbid her from joining the athletics club until her marks at school improve; her brother Zach is annoyed that she chooses a national-level race over his 21st birthday party. ‘I can’t change the date of my birthday to suit your hobby,’ he says, and Mickey is beset by self-doubt: ‘Was this just a hobby, no more important than knitting or crosswords or making a gingerbread house?’

As an adult, Mickey starts to take more control of her life, despite the breakdown of her running dreams and her mother’s illness. Shapiro brilliantly captures Mickey’s dissatisfaction with a life that has taken many choices away from her; the result is ‘a vague general remorse’ that hangs over her, ‘a bodily malaise’. The physical and emotional are clearly linked. At her lowest, Mickey believes: ‘My body had betrayed me. It had let me down in so many ways – too big, too small, too touched, too imperfect, too fractured.’

Mickey’s slow coming-to-terms with her body goes beyond the specifics of long-distance running and taps into a familiar-to-many female experience. When Mickey pushes herself so hard that she stops menstruating, she is finally conforming to the very male standards that surround her: ‘I was like a male athlete now, unhampered by the inconvenience of tampons and blood and hormones.’ Simply existing in a female body is a disadvantage to Mickey. She sees other female runners as ‘both fragile and unbreakable’, an expertly balanced portrayal of sensitivity and resilience, as is Shapiro’s story. The author’s portrayal of this young woman is always honest, and always compassionate.

Tension builds in the marathon chapters, as does our sympathy for Mickey and our investment in her new relationships. At various times, Mickey uses running as an escape, a distraction, a kind of therapy. Shapiro shows us the evolution of Mickey through the evolution of her running, how the thing she once used to use as a punishment can now be used as a form of love instead. Shapiro crafts a perfect ending – somehow a combination of wonderfully unexpected and perfectly predestined. Anyone with the faintest urge to strap on some running shoes and hit the road for a jog will be enchanted by the magic and the chaos of racing that Shapiro depicts:

Adrenaline hitting like a high. Bodies in motion, moving quickly together, finding my space, high knees, fast cadence, catch the breath, keep it steady … Feet on track, the sound and the feeling over and over. Crowds cheering, wind on face, sweat beading on chest in armpits on brow.

Mickey describes the feeling that is ‘akin to panic, to the feeling of a large wave lifting you from the sea bed and threatening to drop you into the shallow water below, the whitewash pressing you down.’ Shapiro encourages us to see life as a long run, but not one that anyone has to win. It’s all about the next few seconds, putting one foot in front of the other: ‘Nothing else exists in this moment but the next step. Not the future, not the past. Only this inhale, that exhale, the ceaseless beat of the heart.’

Shapiro’s physical descriptions of place are evocative, from the Sydney Harbour Bridge as ‘a grey clothes hanger slung over the silver-blue water’ to Bethells Beach, ‘cicadas trilling up on the dunes, the slamming boom of waves’. This keen sense of place shines through the pages, the elements of life in Aotearoa vivid: the summer holidays at home ‘evaporated in a haze of sunshine and boredom’, and even something as mundane as watching her mother cook dinner is rendered with precise sensory detail:

I watched the ghostly spectacle of light on the ceiling as the net curtain waved in the breeze. The smell of dinner cooking in the kitchen grew thick. I heard saucepans, the tap going on and off.

Tāmaki Makaurau is a character in itself, the water around Rangitoto ‘flickering silver in the wind, a messy chop giving the surface the look of water.’ Mickey smells ‘the sweet damp earthiness of the bush, the brackish bite of the sea on the wind,’ and the morning of the marathon itself is beautifully depicted:

The brisk chill of the early morning simmers off in the sunlight, though it’s still crisp. Not a hint of wind and, above us, delicate wisps of thin silken clouds stream and converge on the horizon. Marathon weather.

The city’s geography is delineated in Shapiro’s detailed descriptions of routes and tracks: ‘breaking through to Old Mill Road, looping around Western Springs, down Motions Road, the roar of the lions loud in the evening air.’ Mickey feels an intimacy with the places she runs in: ‘You learn things about the places you run that you can never understand from the comfort of your car.’ And, thanks to Shapiro, so do we.