Edinburgh’s Old Town, a place of old stone and an uncanny silence. It is 2020, the city is in lockdown. ‘I was thinking,’ writes New Zealand-born poet and novelist Lynn Davidson, ‘perhaps I should go home’. But her plan is derailed. Flights are diverted or cancelled, transit visas revoked. Back in her empty flat, wondering what to do next, she ‘felt (invoked, conjured) a shake in the atmosphere and she was there, my Scottish grandmother’s younger sister, Vida.’ As Davidson said in 2021, in a short video accompanying her Randell Cottage writer’s residency in Wellington, ‘It was like Vida had stepped into the room and she said, maybe it is time to start writing about me.’

Vida Grey, Davidson’s ‘crazy-wonderful brave’ great-aunt, was an outlier in the family, ‘a bit erased from family history’. Davidson pins Vida’s birth certificate on the wall above her desk and begins her search, scrolling through Ancestry.com, Papers Past, Find a Grave; rifling through generations of Aberdeenshire farmers; tracking down relations. She glimpses Vida as a 16-year-old on a ship passenger list from Aberdeen to Auckland, arriving in New Zealand with her parents and siblings in 1926. Within four months, her father’s farming dreams shattered, Vida is travelling back to Scotland, leaving four siblings, including Davidson’s grandmother, in New Zealand.

Vida is there again in a divorce case against her husband, Henry, on the grounds of cruelty. Then in an Aberdeen paper receiving a medal from in recognition of her war-time service to the Norwegian Armed Forces in Britain. Another article shows her defending a friend in court on his drink-driving charge. (Five years later she is charged with the same offence.) In 1945, she is in Ben Lomond with a man called Arthur – ‘I think I have found the man who Vida loved and wanted to marry,’ muses Davidson. The following year, Vida remarries Henry.

From such fragments, Davidson uncovers a story of early marriage, motherhood, divorce, alcoholism, voluntary admission to Kingseat Mental Hospital then, as Vida slips the moorings of home and family, homelessness: ‘I think of doorways and a shared bottle to cut through the cold and the comforts or economics of another body’. The last sighting of Vida is in 1986 at Wernham House in Aberdeen, a residential accommodation for those with drug, alcohol and mental health problems.

In Edinburgh, and later back in New Zealand, Davidson interweaves this history with her own story as a single parent, poet and creative writing tutor, and her deep connection to Scotland. She recalls the ‘bolt of recognition’ when she first visited her grandparents’ birthplace as a 19-year-old: ‘I knew the place. I knew the shape of the hills, I knew the light’. In 2016, at the age of 57, she responds to this pull of landscape and old ghosts and relocates to Edinburgh.

In tracking her – and Vida’s – path, Davidson turns to books. Books about writing (Natalie Goldberg); single parenthood (Rachel Cusk, Jacqueline Rose); Scotland (Neil Munro, Margaret Tait, Nan Shepherd). As she writes, ‘These books show me how to manage both my closeness to the land and my distance from it, how my imagination springs from the land and returns to it.’

She follows less orthodox paths, including a ‘family constellation’ session (a sort of psychodrama) and a course on witchcraft run by ‘writers and witches’ Alice Tarbuck and Claire Askew. When she doubts her choice of subject – ‘Is it really her story that I want to tell? – she consults a ‘friend and wise woman’. She and her great-aunt, she is told, ‘are entwined’. Custody battles, controlling men, difficult breakups: ‘Vida cut herself off from her family. Well, at times I’ve done the same to some of my mine… I could sort of see it’.

The resulting book is a discursive exploration of belonging and not belonging, of the pull of home and the play of history. There are moments of extraordinary beauty: an otter playing in the River Esk; a young man on a plane reading a musical score: ‘His hands swam in the current of the music’; the women at the creative writing class leaning into Davidson’s reading of Jessie Kesson’s The White Bird Passes, ‘the way a willow leans towards water’.

She imagines the tearful phone calls when her grandmother in Wellington is told of the suicide of her brother, Davidson’s great uncle, a pharmacist in Aberdeen: ‘What does my seven-year-old father hear? My seven-year-old-father with his piano accordion resting against his chest. Sitting on the steps between the house and the garden, the little puffs from the bellow’.

This lyrical search for threads and connections takes her down myriad byways. Vida’s birth in the village of Lumphanan, where her father ran the local pub, prompts a discussion on the ‘real’ Macbeth, mortally wounded at the Battle of Lumphanan in 1057. On reading about Vida’s childhood performance at Madame Isabel Murray’s Dance School, she can’t help but delve into the story of the well-known Aberdeen dance teacher, who supplemented her income by ‘fitting corsetry and also by teaching rifle skills’. After driving through the North Island’s Central Plateau, she researches the ill-conceived introduction of wild heather by a Scotsman looking to recreate the grouse moors of home. In Dumbarton, Scotland, she beats a baffling path through what was once an expansive New Zealand fernery at the now-abandoned Helensee House.

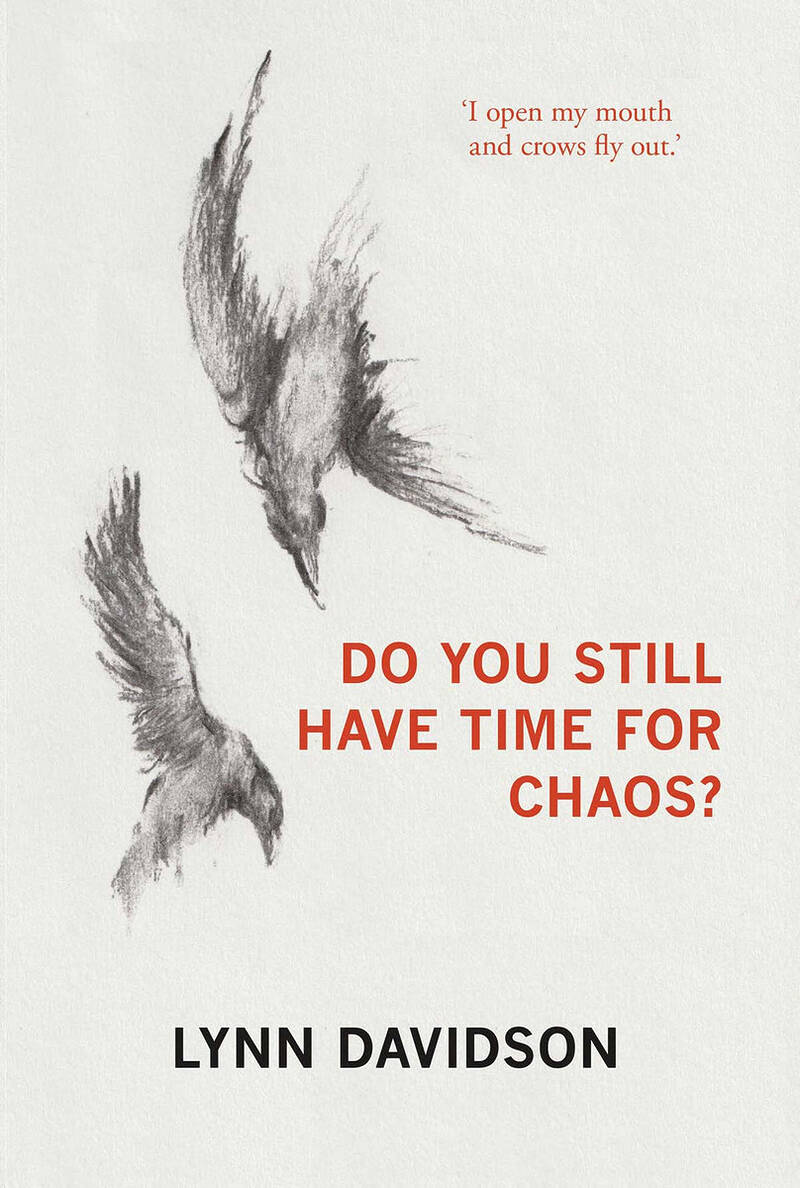

Amongst these many digressions, Vida slips from view, hovering in the wings like an uncertain understudy as other stories unfold on stage. At an art exhibition about the historical oppression of women, Davidson reads the testimony of women accused of witchcraft, including that of Temperance Lloyd, hung in 1682: ‘Did I disturb ye good people? I hope I disturb ye… Have you had enough yet? Or do you still have time for chaos?’ The quote is clearly significant – it gives part of the book’s title – but is it a reflection of her feisty great-aunt? Her own forays into charms and spells and fairie mythology? Or a more general comment on the oppression of women?

This peripatetic approach to memoir is not unusual. As US critic Megan O’Grady wrote recently in The New York Times, contemporary writers of literary memoirs focus not so much on confession and catharsis but on ‘interrogating the form, along with themselves.’ But the amorphous structure of this book and the often-frustrating evanescence of Vida stretch these contested borders of genre even further. The opening chapters/essays lay out the author’s goal to ‘unpack Vida’. The cover of this book describes it as a memoir. Davidson herself has said it is a collection of creative essays, ‘and they’ll interweave – it won’t be a linear book – it interweaves between my own experience of going to Scotland at various stages of my life – and my family’s experience, and then I wanted to also include poetry.’

The resulting poems and essays, some of which have been published elsewhere, form a tangential story of memory, family and landscape. But maybe that is the point. While Vida flickers and fades throughout these pages – we are not even told the year she died – Davidson uses the search for her great-aunt’s story to re-assert her own bonds to people and place. As an adult, she writes, she felt no ‘story of belonging, not one that I could properly tell and wear’. In Scotland she felt parts come together ‘in a way that suggested I belong’.