Death Among Good Men is a somewhat strange hybrid of a book. Assembled by Nathalie Philippe — a senior lecturer in French, cultural studies, and language and translation methodology — it comprises the letters and memoirs of Lindsay Merritt Inglis, a Mosgiel native who went on to illustrious service as a soldier in both world wars, a formidable career as a solicitor and then magistrate (or, District Court Judge, as it is known today), and then to a happy retired life in Hamilton.

Both Philippe and military historian Christopher Pugsley, who wrote the foreword to this volume, make the point that little has been written about Inglis, despite his noteworthy contributions to New Zealand military and civilian life. Pugsley first became aware of Inglis when, as a newly commissioned officer himself, he was browsing in the Waiōuru Camp Library and came across a treatise on machine-gun doctrine written by Inglis.

Philippe found herself drawn to his life when she came across a Frenchman’s diary among Inglis’ papers in the Alexander Turnbull Library. Several years and 400,000 words of Inglis’ archives later, Philippe has shaped a sensitive and often compelling story of a remarkable personality.

Philippe covers young Inglis’ life in a brief introduction: born in 1894 to a banker and daughter of a Free Church of Scotland minister; boarding at Waitaki Boys’ High School (their motto Strong to endure) for seven years until 1913. While at Waaitaki his burgeoning leadership skills were on full display: captain of the 1st XV rugby team his last two years; his last year, he also captained the first XI and was head prefect. Inglis joined the New Zealand cadets and rose to become a second-lieutenant.

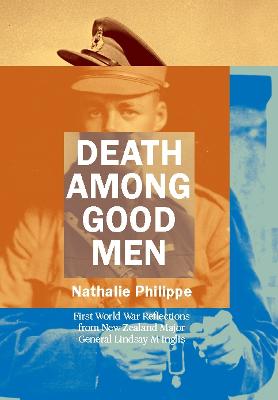

Lieutenant Lindsay M. Inglis (1915), S.P. Andrew Ltd, no date, very likely taken shortly before HMNZT Tahiti departed on 9 October 1915. (Inglis family collection)

Inglis was ‘brilliant in academic subjects such as English, Mathematics, History, French and Latin.’ His two strongest role models while at school were Thomas Holmes Nisbet, later killed in the Gallipoli campaign in August 1914, and Athol Hudson, killed near Armentieres in July 1916. These deaths, understandably, had a great effect on young Inglis, and, later, most probably played a part in his treatment and consideration of the men in his command.

Inglis himself became a role model for younger students. In a 1912 letter, he wrote about his desire to go to university: ‘It will be a good thing to step down off the pedestal, to cease being a little tin idol for kids, and be regarded again as a kid oneself. I think school has just about restricted the ideas of L.M.I. for long enough.’

At the age of 17, in Dunedin, he met and fell for Agnes May Todd, who disliked her first name; she preferred to be called May. In the first of the many letters to May included in the book, Inglis — not quite 18 years old — confessed to wavering between a career in law, which his headmaster was urging him to pursue, or one in the army.

Law is a subject that requires such a long time and rotten lot of swot before one makes enough to live on, as well as being miles behind the other as a life, that personally I haven’t any doubt as to which I’d prefer… What do you think?

Inglis began studying law in March 1913 at Knox College at the University of Otago but after his first two years joined the 1st New Zealand expeditionary Force. In October 1915, Lieutenant Inglis left Wellington aboard HMNZT 32, H.M.S. Tahiti, bound for Egypt. On board, he wrote to May:

The one thing above all others that makes me want to see this business through without getting knocked out is to be able to come back at the finish and put an end to my brave little maid’s waiting.

For the duration of the war, Inglis wrote many lengthy letters to May on many subjects: the fighting, the personalities of the men in his company, his quotidian experiences in the trenches, the leaves he took to Paris, London and Scotland. Inglis uses many pet names for May, including ‘chick’, ‘old lady’, ‘my Pal’, ‘my Dearest’, ‘old chap’, ‘old missus’, ‘my dear old girl’, but with only a few exceptions among the letters excerpted in the book, his closing was, ‘All my love for you for always and “after” too.’ Their correspondence, Philippe writes, ‘played an essential part in Inglis’ survival’, serving as a ‘link to his old life in Otago and to his future hopes’.

The bulk of Death Among Good Men is made up of Inglis’ memoirs, written after his experiences overseas. The memoir excerpts, understandably, are more distant in tone, and there is a certainty to them that can only appear when writing in retrospect. In them we read of Inglis’ arrival in Egypt, followed by stationing in Armentieres, France; training before the Battle of the Somme; and the battle itself. Then there’s the move to Fleurbaix; the action in Messines; the Third Battle of Ypres; combatting the German spring offensive in 1918, the final hundred days; and the occupation of Germany and the return home.

World War I provided the definition of war as ‘months of boredom punctuated by moments of extreme terror’, and even in Inglis’ gifted hands, some of the memoir excerpts drag on. But there are enough moments of riveting action and eloquent writing to keep things moving. He could be quite matter of fact about the undeniable horrors of war:

Early next morning several salvoes of ‘Five-nines’ dropped within a hundred yards of our billet. One of them blew a four horse artillery team and its two drives to pieces on the cobbled street near our main entrance and emphasised the fact that we were now well within range of the German field artillery…

… Away on our right there has been a continuous heavy rumble for the last two days. Then every thirty seconds a crescendo rushing sound ends in an ear-splitting crash about three hundred yards behind us where splinters, clods, timber and smoke spurt up…

…Brick or plaster colour mounds showed where villages had stood. Woods were recognizable [sic] only from sparse and ragged remains. There was no green — only coloured brown earth and white chalk. A railway in the first valley we crossed was everywhere broken, the twisted rails sticking up in fantastic shapes. A few trucks, caught standing on a siding, were a shapeless tangle of rusty iron. Nothing had survived.

It is in his memoirs that Inglis best demonstrates his keen analytical mind, and his growing proficiency at soldiering. After crediting the Canadian Machine Gun Corps for being the first to use the strategy of the creeping machine gun barrage, he explains how he and a colleague positioned their guns

in two batteries, one on each flank of the wood. We opened our barrage at a range of 1700 yards on 600 yards of the enemy’s front line, or 50 yeards per gun, and made seven lifts of one hundred yards each at intervals of one minute. [Using a small barometer and thermometer he’d brought from New Zealand, he] added one hundred yards elevation for temperature and barometric pressure… The opening barrage came down perfectly on the German front line, the bullets which struck the parapet throwing up tall feathers of snow.

Inglis, always confident in his judgement, was unafraid to point his scorn up or down. ‘The greatest misfortune the N.Z.M.G. Corps ever suffered was the posting to it of Lt Col. Blair as its senior officer,’ he complained in 1918:

Blair had no technical knowledge of machine guns, and he never grasped the principles of their tactical employment. To these defects he added a capacity for sneering and injustice that not only deprived him of the respect of his subordinates but soon earned for him the dislike and even the hate of all ranks…The N.Z. Machine Gun Battalion, composed of men second to none in fighting quailty, did its job in spite of, and not because of, its C.O. How we used to chafe under him. It was exasperating to realize how much more effective our work might have been under the right commander.

In a letter to May, Inglis wrote: ‘Truly, old chap, a sense of humour is the most saving of all graces in this game. Without that one would find things indescribably terrible and ugly’. On leave in Paris, Inglis convinced a group of locals who didn’t recognise his uniform that he was Mexican, leading them to cry ‘Vive la [sic] Mexique’. Later, when a German shell hits his observation post, Inglis spotted ‘a cubic inch of something red and raw looking on the ground’.

‘I say, Corporal,’ I asked Silby, ‘is that piece of meat off you or me?

Silby looked at it stupidly and replied, ‘I don’t know, sir. Let’s have a look.’

When we had solemnly examined each other without discovering any wounds, I picked up the piece of flesh. Someone had dropped a piece of tinned tomato.

Between the memoir and the letters, we see both Inglis’ sense of duty and his utter devotion to May. In November 1917 he writes to her:

In my secret self I confess I often fall to arguing whether it wouldn’t be ever so much better to get a ‘buckshee’ [a wound] that would finish one’s war days and take him back to all the things he longs for…I want nothing and never will want anything like I want to get back to you, darling; but I just can’t come till I have to. I hate the war, I’m sick of it, I have had enough; but I can’t leave it till I’m forced to.

In the event, Inglis survived the war, of course. He married May and they had two daughters. He worked as a solicitor in the family firm of Inglis and Inglis, and remained connected to the Territorials, then the Reserve. At the outbreak of World War II he joined the 2nd New Zealand Expeditionary Force: he was 46. By the end of the war, he was Brigadier Inglis, appointed President of one of the Allied Control Commission Courts in Germany. This treated cases involving crimes committed by German or, occasionally, Allied nationals against the occupying powers. After returning to New Zealand he became a magistrate – a District Court Judge – with his last appointment to Hamilton in 1953. Inglis died of complications following cataract surgery in March 1966.

Lindsay M. Inglis and May Todd’s wedding, 3 December 1919. (Inglis family collection)

This handsomely designed volume includes 32 pages of photographs. There are issues that a judicious editor and/or proofreader might have caught, not least some errant punctuation and miscounting of appendices. Many of the maps were reprinted from volumes published in the 1920s, which explains why they don’t always include all the place-names mentioned in the text, and why some are too small and unclear to be useful.

The experiences of Inglis reveal just one man who performed extraordinarily in extraordinary times. Every year brings more books about the Great War. Especially noteworthy, for example, are the new edition of Alexander Aitken’s Gallipoli to the Somme: Recollections of a New Zealand Infantryman, edited and introduced by Alex Calder, and David Hastings’ Odyssey of the Unknown ANZAC, both published in 2018 by Auckland University Press.

The publication of Death Among Good Men, with the insights and rich details that Inglis’ letters and memoirs provide, leads inevitably to the question of what else is out there. The last New Zealand veteran of World War I died in 2003. But somewhere, perhaps in a forgotten trunk or box or shed, or even in a library, there are other written records and testimonies that will add to our understanding of that increasingly distant time. Lest we forget.