‘Punk, to my mind, differs from heavy metal by both its sly humour and its irony,’ Darcey Steinke wrote in her recent essay on Nick Cave, ‘God is in the House’. ‘Also its nuanced theological engagement. While much metal takes on the mask of destroyer, punk is the wailing of the destroyed.’ Punk, in various forms that began in the 1970s, was broken music for broken people. It was protest music that gave shape and voice to dissent, resistance and nay saying. It was about resistance to the oppression of boredom and the world’s moral corruption and offered the self-obliterating power of noise. Or as Wellington writer David Coventry puts it in his second novel, Dance Prone: “At seventeen we craved velocity. Volume and haste. Massive, thickening waves of decibel and speed.”

The broken people in Dance Prone are Neues Bauen, a post-hardcore four-piece from the fictional college town of Burstyn, Illinois. Frontman Conrad Wells narrates the story as the band tour through the south-west of the United States during the closing weeks of 1985, playing halls, bars and house parties, where gigs frequently devolve into violence, and friendships and rivalries develop with other bands across a pre-internet underground network formed by venues, labels and fanzines (Wells is supposedly writing a tour diary for scene bible, Maximum Rocknroll). Coventry clearly knows what he is talking about, not just as a student of the era but as a musician who played in bands around Wellington in the 1990s. The book is crammed with cult band names, from Big Star to Mission of Burma to Christchurch’s Scorched Earth Policy – at times, it risks becoming a guided tour of Coventry’s record collection, complete with annotations. He is very good on the urgent, kinetic action of a band on stage, the unsteady sense of making something that could soar or collapse at any moment:

The beauteous arrangement, this shriek amidst the rhythm and throb. The fellow running the monitors pulled me up and reset the mics and I was back across the other side choking the neck of the guitar. Queues of army jackets arguing to leap the stage first. One stood arms out on the monitor, Blair Potaski with his mouth bleeding.

There is a lot of blood and the violence doesn’t just happen on stage. Conrad is raped in the back of the band’s van and the plot becomes a mystery, spanning decades and continents, to find out who did it. On the day of the rape, guitar player Tony Seburg shoots himself in the face and, to bookend the tour’s violence, a death mirrors that of Minutemen singer and guitarist D.Boon in a van crash in Arizona near the end of 1985. A dense story is rendered even trickier by Coventry’s frequent impersonations of Don DeLillo’s unique prose style. Coventry has said that his life was changed at 21 by reading DeLillo’s White Noise, and it’s clear that the influence has been a deep and lasting one for him (The Names is namechecked here). There are sentences throughout this book that could almost be mistaken for DeLillo’s brilliant sentences – ‘Water and whatever bursting in the lights’ is one picked at random. The same could be said of cryptic dialogue such as this:

‘She invoices. She sends samples. These are the things of ordinary lives.’

‘Ordinary lives.’

‘It’s this thing I’m doing.’

At its best, DeLillo’s prose can get at something transcendent beyond the page, an impression of knowledge passed on in some extrasensory way. That might be why DeLillo refers to art and cinema so often, as they do the things that language can’t do. DeLillo’s individual sentences can also convey an epigrammatic wisdom (‘the future belongs to crowds’ in Mao II) that Coventry’s writing never quite approaches. ‘Within all great cities time and space are compressed, extended; the only calculables are food and its smell,’ Conrad muses. Or later: ‘Secrets make the world alert and constantly awakening.’ That sounds good but some readers will pause at sentences like that to wonder if they’re true.

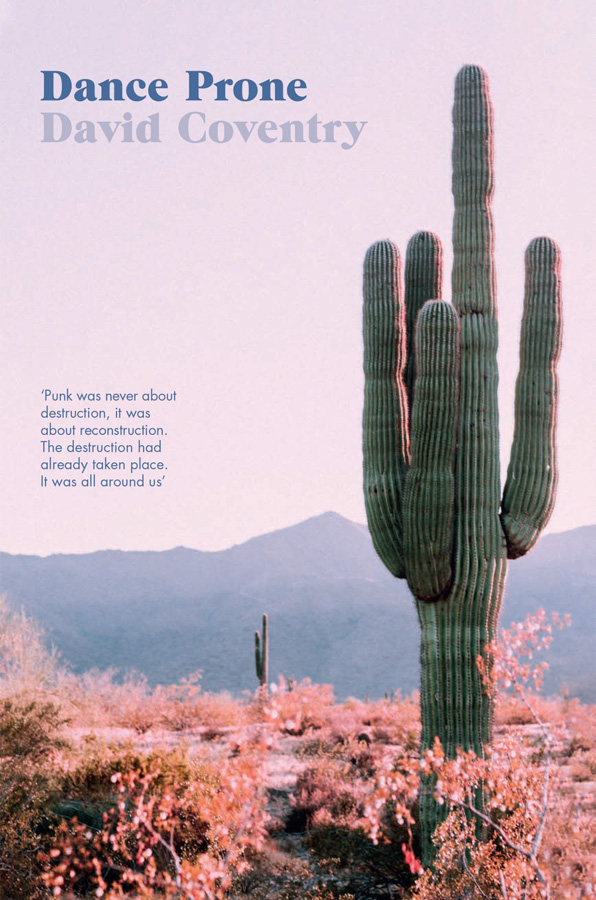

Like DeLillo, Coventry brings art and cinema into the picture. Conrad visits a site in north Africa that he knows was a location for an Orson Welles production; old film of the band is found online in 2019 and scrutinised as though it is mysterious footage of Hitler or JFK in a DeLillo novel. There are large, environmental, cultish art projects that also have an air of DeLillo about them. But one man’s trauma is really at the heart of this travelogue guided by violence or excavation through the painful layers and gaps of memory. It can be a murky and challenging experience. Even when Conrad finds himself in the bright deserts of the US or North Africa, he and his story remain enshrouded in a darkness he just can’t shake.

This review was originally published on the Academy of NZ Literature site.