At the endlessly useful NZ On Screen site, you can find an hour-long documentary, directed by Sam Neill, titled Red Mole on the Road, that was first broadcast on local television in 1979. It seems to be all that can be easily seen or heard of a nearly legendary, avant-garde theatre group that was said to have been dreamed up by Alan Brunton and Sally Rodwell in an opium den in Laos in 1973 and only ended with Brunton’s sudden death in Amsterdam in 2002. A lot happened in those three decades, and quite a bit of it happened overseas, but it was ephemeral by its very nature – hard to repeat, impossible to copy, rarely recorded.

Brunton had a kind of missionary zeal, born of 60s idealism and a Rimbaudian derangement of the senses (‘I want to go where there’s no beyond,’ he said). The group put together cabaret, slapstick, comedy, political satire, songs, puppetry and mask work. Someone called it futurist vaudeville. Other people called it surrealist. A left-wing perspective on the times was a given (a character with a pig’s head didn’t need much explaining to New Zealanders in 1979), and their itinerant outsiderness puts them between the last gasps of hippiedom and the imported shock tactics of punk rock. The mid-late 70s was a fertile time for oppositional culture that challenged the national slumber.

Red Mole on the Road gives you as good a sense as anything else might of what Red Mole did, what they looked like, why they existed and what New Zealanders of the 1970s thought about them, whether they were ecstatic school kids in Murchison, bemused shoppers in Christchurch or discerning theatregoers in Auckland. As he steers one of the group’s rickety vehicles from south to north, Martin Edmond, who was in the group as an actor, technician and critic, or historian in training, tells Neill that their job was to show ordinary people the gap between what they think is going on in New Zealand, and what the reality is. He’s in stage make-up as he says this, and he’s wearing a Charlie Chaplin bowler hat. Red Mole clearly didn’t mind committing the cardinal sin in New Zealand cultural life, which is being pretentious. Edmond’s central place in the film, as a spokesperson for Red Mole, also seems contrary to the sense he gives us in his own, newly published account of being marginal or peripheral, and somehow tolerated in the group. Edmond’s account refers a few times to the dominance of the so-called Gang of Three, made up of Brunton, Rodwell and Deborah Hunt, who were also in a ménage à trois. Well, it was the 70s.

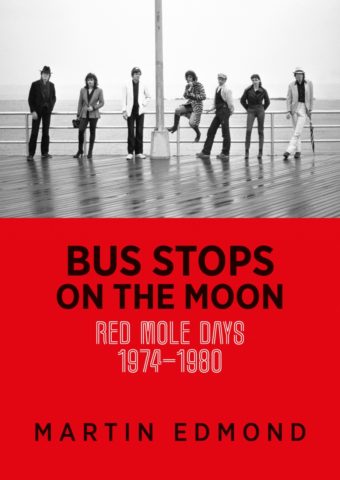

That account, Bus Stops on the Moon, is really doing two things at once. On one hand, it’s a detailed history, drawing on the Brunton and Rodwell archives, of Red Mole’s activity during the six years he was attached to the group, a time when he was also married to musician Jan Preston, sister of film-maker Gaylene, who led the associated band Red Alert. Using archival papers, contemporary reviews and his memory, and he admits that the latter may be the least reliable of the three sources, Edmond reconstructs a series of Red Mole shows. Sometimes that can be like hearing someone recount their dreams, as in this description of the action in the Polynesian noir Slaughter on Cockroach Avenue, from 1977:

‘Frank sent his offsider, Sunshine, a pest exterminator, up north to look for clues. There were scenes in a country store, at the Pūhoi pub, on a commune where a group of hippies worshipped a guru called Don Heke. They took ritual doses of tutu berries harvested from the grave of James K. Baxter at Jerusalem. Sunshine, wearing a rat mask, ended up dead, killed by the hippies in a drug-induced frenzy. Frank discovered the body in a nightclub called The Crypt, where he had gone to rendezvous with the Blonde. Maybe she had something to do with the death of her brother after all.’

As Edmond says, Slaughter on Cockroach Avenue ‘had a storyline that didn’t cohere and wasn’t meant to either’. Arthur Baysting’s Neville Purvis character, later immortalised as the first person to say ‘fuck’ on New Zealand television, was in the show, as were two dancers from Limbs and Midge Marsden’s band the Country Flyers. Amazingly enough, this wayward exercise in 70s surrealism was performed at Phil Warren’s Ace of Clubs in central Auckland for a nightclub crowd that came out to see Marcus Craig’s saucy drag act, Diamond Lil.

As well as being a Red Mole history, Bus Stops on the Moon is also an Edmond memoir that links The Dreaming Land, the book that covered his rural childhood in the 1950s and 60s in a fairly straightforward way, to the more hallucinatory, less reliable Luca Antara, which opened with Edmond’s arrival in Sydney in 1981. This is the decade in the middle, but the peculiar thing is that Edmond seems less free here than he did when he recollected his childhood or other parts of his adult life, a problem he anticipated when I interviewed him about The Dreaming Land in 2015 (‘There are things about those times I don’t want to write about,’ he said of the 70s). There is a greater sense of detachment and distance than before, and the personal life, the interiority, is often missing. By the end, you can see that it’s about how Edmond’s slow but steady development towards a point where he could call himself a writer was interrupted by the years when he ran away with the circus. He goes from writing art reviews for the university paper to helping Brunton, Ian Wedde and others with the avant-garde journal Spleen to taking on a day job as a writer of adult fiction while Red Mole were based in New York (he can recall one title of the six books he wrote under pseudonyms: Diary of a Well-Whipped Wife). Writing, he learns, is all about sitting down and delivering, even if it’s pulp or porn.

Bus Stops on the Moon is also valuable for the ways in which Edmond measures the tension and paranoia of the times. It’s the 70s Wellington of the Bill Sutch spy story and the secretive, coded world of Carmen’s Balcony nightclub, where Red Mole famously did a season. It’s the Auckland of the pre-gentrification Ponsonby. It’s San Francisco when Jonestown happens, Harvey Milk is killed and the entire city seems ‘death-obsessed’. A three-day drive across the country puts them in New York just as the Three Mile Island nuclear plant is melting down. Blackouts across Manhattan seem apocalyptic. Events in the news start to appear like omens with personal significance.

Was it really as strange and dark as all that? Edmond concedes that ‘The amount of dope I smoked in those days might have contributed to my paranoia’. He knows they’re talking about him when he hears someone say, ‘You mean that guy who always looks like he’s out of it?’ Flirtations with madness and altered states are familiar territory for Edmond, who went to where there was no beyond and came back to tell us about it in Chronicle of the Unsung, Dark Night, Luca Antara and The Resurrection of Philip Clairmont. But it’s only in the last chapter that the love story and long-running creative partnership between Brunton and Rodwell that was the heart and soul of Red Mole comes fully into view for both Edmond and the reader. It leaves you wanting to know more about them.

This review was originally published on the Academy of NZ Literature site.