Recently, as it is inclined to do every few years, Aotearoa New Zealand’s ‘book world’ has been bemoaning the poor sales of New Zealand fiction. The figures quoted are much as always: 5% of total book sales in New Zealand; each book lucky to sell 2,000 copies. The problem cited is as ever New Zealand fiction’s reputation for being ‘dark, literary and difficult’ (as one novelist put it). The solution? Once again, ramp up the number of commercial fiction titles and afford them more respect, including at book awards.

I think we can safely say Breach of All Size editors Michelle Elvy and Marco Sonzogni didn’t get the memo. Or if they did, they crunched it into a tiny ball and tossed it in the bin with a defiantly muttered ‘Whatever’.

Elvy is a prominent presence in New Zealand flash fiction, including as founder of National Flash Fiction Day; Sonzogni is a cultural dynamo at Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington, who is fast becoming New Zealand’s leading literary conceptualist and trickster. Witness his Dante double last year: More Favourable Waters, in which 33 New Zealand poets reflected on Dante’s Purgatory; but moreover the translation of Dante’s Divine Comedy in which he collaborated with illustrator Ant Sang to replace every instance of ‘ant’ in a word with a drawing of an ant. Who could have anticipated such an antic?

Those books were for the 700th anniversary of Dante’s death. Now it’s James Joyce’s turn — a writer who’d approve of Sonzogni’s tricksterdom, being himself a master of formal tomfoolery and experimentation, puns and pastiche, erudite allusion, and alliteration aplenty.

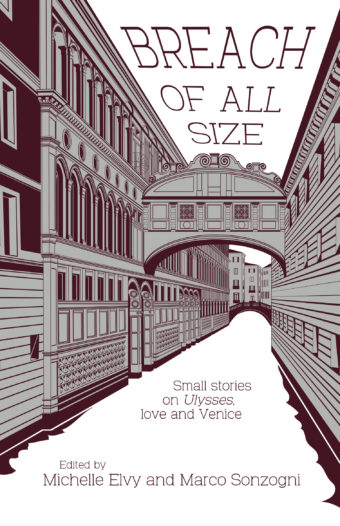

Breach of All Size marks the centenary of Joyce’s 1922 novel Ulysses. For good measure, it replaces Joyce’s Dublin setting with Venice, which last year celebrated the 1,600th year of its founding in 421. The 36 contributors were asked to write love stories or poems inspired by Ulysses and set in Venice. The pieces were to be short — mere glimpses — no more than (of course) 421 words. Compared with Ulysses’s 265,222 words. The book’s title is a nod to Joyce’s punning play on Venice’s Bridge of Sighs. A multilayered nod, as we’ve come to expect from Sonzogni. And there are more layers to be uncovered from both him and Elvy in their introductions, as well as from the University of Melbourne’s Catherine Kovesi in her foreword.

Breach of All Size is definitely literary, then. But what about dark and difficult? Not really — although you could be forgiven for thinking it would be.

Ulysses is the 700-page peak of early twentieth-century literary high modernism — a peak many a reader, despite many an attempt, has failed to ascend. It was banned on first publication, accused of obscenity — the ‘obscenity’ of its unglossed depiction of everything from sex to defecation to corpses in a graveyard. And not in such genteel language, either. Joyce wasn’t interested in the decorous deceits of the middle classes and the literary establishment. ‘There’s nobody in any of my books who’s worth more than a hundred pounds,’ he once said. (That’s about NZ$11,500 in today’s money.)

Leaving aside Ulysses’s deep immersion in what we’re now familiar with as the ‘stream of consciousness’ of characters — which in Joyce’s hands is less the gentle streams of our contemporary writers and more like the torrent of a river in flood — the single day (16 June 1904) on which the novel is set is packed with what for many 2022 readers (and a fair few in 1922) will be impossibly recondite references, not least to Homer’s classical Greek epic poem the Odyssey.

You probably ought to have read that, and for the complete experience might also consider Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, the 1916 novel in which he introduced and provided much of the background to one of Ulysses’s protagonists, Stephen Dedalus. A working knowledge of the Symbolist movement wouldn’t go amiss, either.

So that’s a significant and challenging chunk of reading to get through before you even reach Breach of All Size. Don’t be deceived by its slimness and low page number. (More Sonzogni tricksterdom?)

Except. In the first story, Diane Brown’s ‘Stately, plump’ (titles have been assigned to contributors from phrases in Ulysses, those words being the novel’s first), a wife admits to her husband she’s never read Ulysses: “I’ve read the beginning and the end, to get the flavour, but there’s always something else demanding my attention.” Is that Brown also speaking? Certainly, although their contributions remain enjoyable and for the most part fertile flights of imagination, she and a number of the other writers give little sign of having read the novel. So readers can afford themselves the same let-out.

But, just as the anthology’s better stories and poems are those that engage with Ulysses more closely, the better reader experience is one that recognises when and how they’re doing so. These pieces include, appropriately, the last story, Selina Tusitala Marsh’s ‘Yes’. Its title is the final word in Ulysses, the end of a long monologue by another protagonist, Molly Bloom. The monologue is as renowned for being a single unpunctuated sentence of nearly 50 pages as it is for its sexual and bodily candour. Marsh distils (perimenopausal) bodily candour and other themes, with Venice and its canals put to metaphorical service, into her own single unpunctuated sentence, over a page-and-a-half that likewise culminates in the word ‘Yes’. With a lot of other yesses along the way, Marsh builds to a glorious crescendo of affirmation.

Two of the anthology’s other poets, Anne Kennedy and Lynley Edmeades, best capture the subtler aspects of Joyce’s style in ‘The nearing tide, that rusty boot’ and ‘The weight of my tongue’. That style amounted to more than abandoning punctuation. (Which he only does in Ulyssses in Molly’s monologue.) There were the missing words to convey the jumpcut fractured continuity of consciousness; the portmanteau words; the neologisms. Edmeades goes one better — and meta — and deconstructs Joyce’s technique before our eyes by crossing out her ‘missing’ words rather than erasing them completely.

If Venice is a city of love (and prescribed to be so in this anthology), Joyce’s Dublin is one of lust, and several of the stories and poems blend the two, such as in the libidinous energy of Lloyd Jones’s ‘Another victory like that and we are done for’; Sudha Rao’s sublimely sensual ‘Diamond and ruby buttons’; the straying eyes of Emma Neale’s honeymooners in ‘Bald, most zealous’; and the bawdy bathos of Trish Gibben’s innuendo-laden ‘To enter or not to enter’.

Sexiest of all is the following from Renée’s ‘Moment more. My heart.’, the story of a woman farewelling her seasonal farmhand lover:

The tree smells of you, of sun, it smells of the end of summer, the end of time, the end of us. My hands smell of you. Six Saturdays, six Sundays. Six Friday nights waiting. Six Monday mornings waking. Two days. Twenty hours working, two hours eating, washing ourselves, our clothes, swimming, the rest of the hours sleeping. Or not sleeping.

While many pieces pay stylistic and formal homage to Joyce — even if the stylistic and formal innovation is sometimes their own and owes only its spirit to him — others tip their hat in other ways: a Molly here, a prostitute or priest there. A newspaper office. The flâneurs.

No matter how closely they’ve engaged with Joyce — or for that matter with Venice (it’s no more than a variety of apple in Renée’s story) — most of the writers have let their imaginations roam productively with the challenge set them. As a result, you’re as likely to encounter the repercussions of institutional abuse (not once, but twice — in Jenna Heller’s ‘The inner organs of beasts and fowls’ and Wes Lee’s ‘A sugarsticky girl’) as you are a piece of historical fiction (Karen Phillips’s ‘Of soldier and sailors’), sibling enmity (SJ Mannion’s ‘Just you try it on’) or a droll non-fiction travelogue (Paula Morris’s ‘Hardly a stonesthrow away’).

There’s a touch of the travelogue about a few fiction pieces too; an inevitable touristy take on the city by writers from the other side of the world. And a touristy take means a certain Venetian milieu is missing. There are few people here worth as little as a hundred pounds.

Although the pre-modernist literary style and framing of one or two stories might make you wonder whether Joyce’s revolution of the word (the title of Colin MacCabe’s landmark 1979 structuralist study of him) has declined into a rebourgeoisification of the word, there are only a couple of actual duds in the book.

Elvy and Sonzogni are to be applauded for the daring of their anthology’s conception and the success of its execution. By turning the virtues of Ulysses’s expansiveness and intense immersiveness on their head, they and their contributors have shown how brevity and a casual dip can be virtues, too. Breach of All Size is unlikely to breach the 2,000 copies sales barrier or enrich the bank balances of anyone involved. But it will provide those who do read it with a more valuable kind of enrichment.

This year is also the centenary of TS Eliot’s poem ‘The Waste Land’, another beacon of literary high modernism. Dare we hope Elvy and Sonzogni have another anthology planned for that?

Sadly, we’re still seventeen years away from the centenary of Finnegans Wake, the 1939 novel in which Joyce substituted Ulysses’s stream of waking consciousness with one of sleeping consciousness, and wrote a book virtually unintelligible to most readers.

What might a febrile mind like Sonzogni’s make of that anniversary?

This review was originally published on the Academy of NZ Literature site.