When I was young, my family would drive north from Invercargill in a rattly little Mk 3 Cortina for the summer holiday. The drive seemed endless, the road cutting through dull processions of paddocks, the three of us kids in the back seat, squashed between the camping gear, uncomfortable and fractious and bored. The only thing that kept me from murdering my sisters or from dying of boredom myself, were the kāhu wheeling around out the window. I would press my face to the manually wound window and watch the birds swooping the wide Southland skies, drawing lay lines in the air with their wingtips.

The kāhu, or swamp harrier, or Australasian harrier hawk, is our largest bird of prey and a wondrous hunter to watch, when you are nine. In the deep south the roads are long and straight and the horizons wide: I could see the bird’s full circuits; I had all the time in the world to watch and wonder at what they were thinking.

NZ Birds Online tells me now that those hawks had murder on their minds; that they were on the hunt for sparrows or mice, methodically quartering the ground like army operatives, or watching for carrion — roadkill pre-prepared by the last Cortina that sped by – but to me those kāhu were bird ballerinas, or warrior hunters, or brown-winged heroes, perhaps on a quest or a mission, perhaps on their way to fulfilling some sort of prophetic destiny, or perhaps just trying to escape from their siblings in the nest, who no doubt, were just as annoying and sticky-beaked as mine.

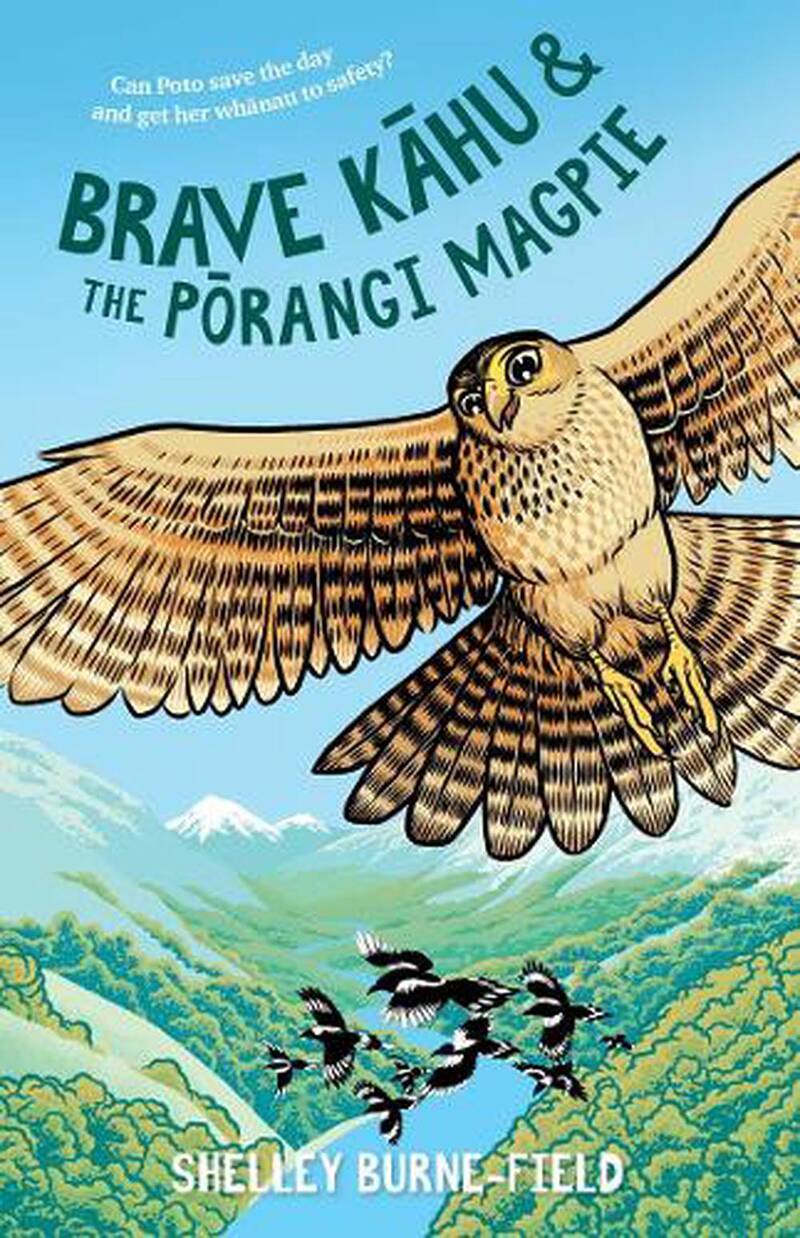

Hawkes Bay writer Shelley Burne-Field’s debut novel for children, Brave Kāhu and the Pōrangi Magpie, puts both those birds and those sibling dynamics front and centre. Aimed at readers of about the age I was at the peak of my harrier hawk fascination, it is the first-person account (first-bird account?) of a young kāhu called Poto, a brown-winged heroine on a mission, irritating siblings in tow.

Poto is a ‘perfect kāhu’ — an expert hunter, excellent on the wing — much to her sister Whetū’s annoyance. Poto can’t understand why Whetū can’t fly like she can; Whetū, for her part, would rather ‘peck her own toes,’ than take advice on how to be a better hawk from her sibling. Younger brother Ari is also something of a frustration. ‘Back at the nest I just didn’t know what to do with him. He’d either twirl around and dance with his shells or play dead or who knows what. How many other kāhu did that? Not one.’

Poto longs to spread her wings and fly north towards adventure, but with their father dead, she must stay and help out at home. When their mother is killed and little Ari badly injured by a flock of vicious magpies, Poto is forced to embark on a different sort of journey. It’s a mission that will see her lose everything — her home, what’s left of her family — if she doesn’t succeed.

Poto has a lot to contend with. An earthquake is coming that will destroy the local dam and flood their valley (they know this thanks to Nīkau, Poto’s best friend who can conveniently see the future). Then there is wild weather, feral cats, giant rats, vicious stoats, and a tricksy, malevolent taniwha, not to mention that murderous flock of magpies, hell-bent on taking over the valley, waiting for their chance to strike again. Poto must work with her sister to get their injured little brother Ari safely through it all.

We love our birds, we Kiwis, and Kiwi authors are no exception. Take a peek inside any children’s bookshop in Aotearoa: the shelves are covered in feathers; beaks poke out from every cover. Brave Kahu and the Pōrangi Magpie takes a fresh, hawk-like dive into the fictional lives of our native manu, immersing young readers in a bird world full of idiosyncratic personalities and physiologies. Just like our real kāhu, Poto has the hawk’s famously sharp sight — she can ‘spot a mokomoko shedding its tail on the side of a cliff from the other side of the swamp’; she dreams of one day following the sky-trail, the intangible migratory path that ‘glowed and stretched to all horizons’ all the way to Rangitāhua. It’s true that kāhu have been known to visit islands as far north as Rangitāhua — the Kermadec Islands — halfway to Tonga.

Young Poto picks up a caravan of manu mates willing to help her on her epic rescue mission. As well as Nīkau the Matakite, there is bumbling kereru, Iti; Manaia, the elegant karearea; an ancient albino kiwi; and two kind, trinket-collecting weka, ‘ground dwellers’ that Poto is very happy to have on her side.

The story draws on myth, legend, fact and fiction, from te ao Māori and te ao Pākehā, from mātauranga Māori and from the natural history archives. Burne-Field weaves these threads together to form a convincing bird’s eye view of the South Island valley in which this story is set.

Reo Māori words are used often within the English text — many that young Kiwi kids will already be know, some they won’t; there is a glossary at the back for reference. If young readers don’t know what tūtae is when Poto and is friends find piles of it at the bridge, for example, they certainly will by the time Tai the weka gets a fright and declares, ‘I almost tūtaed myself’ a few pages later, or when Iti, the berry-drunk kereru ‘passes tūtae’ next to Poto with a noisy splat. ‘I’m all goods,’ Iti slurs when she crashes into a mānuka tree after trying to flee the scene.

Poto’s siblings, Whetū and Ari, are particularly well-drawn characters — to the point that I wondered whether either one of them might’ve been a better choice of point-of-view character. Both seem to be more in conflict with the world around them than the ‘perfect’ Poto and have backstories thick with drama and emotion. The memory of their dead and imperfect father lingers: he was great with Poto, who was good at everything, but not so much with little Ari and Whetū who didn’t — or couldn’t — fit in. ‘Ever since Pāpā died,’ Poto tells us, ‘there were times Whetū would fly off in a rage and I would find her at the top of a cliff, trying to sing like a tūī, but just squawking. That was Whetū: raging and singing.’

Little Ari, it becomes clear, is takiwātanga (autistic). ‘He’s a unique little thing,’ as the weka Piki explains. ‘He lives in his own time and place.’

‘I miss my mama!’

‘I’m sorry, Ari.’

‘I don’t miss him.’ Was it so easy to forget Ari’s suffering because it hadn’t ever been my neck at the end of Pāpā’s words? Ari had also watched Mama take her last breath.

‘I’m so very sorry,’ I whispered, but Ari had burrowed into Whetū’s neck.

‘He’s at the end of himself,’ she muttered.

I was at the end of myself, too.’

Although the drama or conflict is often centred on her siblings, there is plenty to keep Poto busy and plenty to hold the reader’s interest. While Poto, Whetū, Ari and their mates battle their way out of the great flood’s path and deal with challenges both physical and emotional, across the valley, more danger awaits.

The glow from the rising eye of the sun burned up from the ocean horizon, lighting up the tree trunk with a dream of fire. All sizes of makipai perched on branches above and below their leader, Tū.

With the poetic introduction of the evil head of the magpie clan, the story really takes flight. The makipai want the valley that Poto and her siblings call home and they’ll stop at nothing to get it. Tū is vicious and doesn’t hold back.

Tu enjoyed scaring others out of their feathers. She enjoyed their shivers, yet it repulsed her as well. She could smell the fear on this idiot’s skinny toes. Hiwa could wait. Tu never gave fear a chance to flutter her own feathers. She’d learned to chew it up and swallow it like the liver of a tui.

Yes, these are birds we are dealing with, anthropomorphised for a story for children but there are still serious themes at play: absent and imperfect fathers, bad guys who unceremoniously dispatch perceived rivals, picked-on neurodivergent kids, dead and much-mourned mothers.

Mama. The wind sighed. Mama. The voice seemed to seize my bones. I lifted my beak to the moon. I wanted to cry out, to rage, but the wind picked up, lifting my feathers and bringing me back to the night. The scent of Mama’s blood hung in the air.

Beautiful writing and big, serious stuff for young readers. But despite the high body count, themes of aroha and understanding shine through, like the gleaming stones at the bottom of the taniwha’s pool. The kāhu’s story is a celebration of relationships; of connection with our natural world as well as with each other. ‘We were together. Tuakana and teina. Sisters. The same bones. The same feathers,’ Poto says, having learnt that everyone — annoying sisters, brothers who ‘don’t fit in,’ the shy, the different, the diverse — all have something to offer, all have something to give.

The book is sad at times. Too sad, I wondered, for young readers? ‘Nah,’ says my 10-year-old, reporting back after reading the book himself. ‘It’s not too sad. It’s good,’ he says, pointing to an early passage where the valley is characterised as shaped like a feather. ‘It has good descriptions.’

There are indeed ‘good descriptions’ throughout, great writing in general, the sort of world building that will keep readers thinking about its feathered community long after they’ve closed the book and have them watching those swooping kāhu from car windows with fresh eyes, wondering about what they are hunting, what predators they have escaped that day, looking out for that sky-trail they are following, north, perhaps, towards adventure.

2 Comments