Anna Smaill’s second novel is set in a contemporary Tokyo of long commutes, convenience stores and drab lookalike apartment buildings. It’s also a supernatural city, capable of an unsettling strangeness amid the uniform array of salarymen and school kids, responding to the essential loneliness of some of its inhabitants.

There are two point-of-view characters: Dinah, a young New Zealander in Tokyo to teach English, and her chic older colleague Yasuko, who begins to take care of the adrift new arrival. Both carry invisible psychic burdens. Dinah’s twin brother, Michael, a mercurial personality and musical prodigy, has killed himself. He ‘was gone and would not come back again’, Dinah knows, but in Japan she can’t escape her memories and guilt. Before long he materialises in her tiny apartment, able to talk to her and wander the streets with her in the evenings.

Yasuko is quite unlike the other teachers, with their petty concerns and staffroom politics. She has had ‘powers’ since she was thirteen, able to converse with creatures. A cat speaks to her, calling her a silly girl, and like Alice passing through the looking-glass, Yasuko is led into an alternate universe of enigmatic declarations, ‘irritating riddles’, advice and warnings. This communion with the natural world is both exhilarating and overwhelming:

There was so much to take in that some days she did not even get to the school gates. The trees swaying in the wind spoke to her; sunlight dappled the ground. There were patterns everywhere; all were filled with meaning. She walked through the park and heard the chirrup of small frogs and the tadpoles’ stress as they pushed out their new legs into the silted water. Transformation is pain, their noiseless voices whispered. You have to give up your thin skin in order to change. She thought that she would like to move between the elements, though she did not yet know how.

Yasuko’s ‘powers’ emerge in intense episodes that her family interpret in a different way, as depression or psychosis. Unlike Alice, Yasuko doesn’t dismiss her experiences as a dream or as imagined in any way, and this has consequences for her: estrangement from her father, the loss of her job, a fractured relationship with her son. ‘Power was not an easy thing to own,’ she realises. ‘The world was sharp, and everything had a texture that brushed up against her’.

Dinah lives in a looking-glass world of her own. (‘Dinah’ is the name of Alice’s cat in the Carroll books). Her dual existence has been formed by her brother, both before and after his death. Growing up, Michael was the gifted one and she ‘was just the one who listened, and watched’. They were ‘mirror images of each other’, even sharing dreams. ‘I think for half of my childhood I did not know what was real,’ Dinah says.

Michael told me that if you looked through the window in my mother’s room, you could see into a different world, a different life. If you looked long enough. It was like a little round orbit, a lens. He went through into that world.

Before Michael begins appearing in Tokyo, Dinah is profoundly alone. She is convinced that the park is empty and that her building is empty, moving through the mega-city in a bubble of misery. This often renders her a less interesting character than Yasuko, both in Tokyo and in the resurfacing world of her memories.

Bird Life is a meditation on grief of different kinds. Yasuko tells a pregnant coworker that motherhood is ‘a kind of grief’ that begins when their children are born and

because they are born. It starts because each breath they take contains the world in which they never lived at all. And also, the world after they have ceased entirely to exist. As soon as they take that first breath, that is what is loaded into your shoulder bag. Every moment, including their death. What can you do, except carry it?

With such an intense mother, it’s no surprise that Jun wants to escape into student accommodation and some respite – ‘space’, he calls it, after Yasuko bombards him with texts. Dinah decides to help out by meeting (and berating) Jun: he is blandly handsome and conveniently fluent in English. The sexual tension between them becomes yet another thrumming string in Dinah’s on-the-edge life.

Her own grief is a raw, gaping wound that Dinah seems incapable of tending. She eats and dresses carelessly; she sleeps on a bench in the small park near her apartment. For Dinah, birds are like any of the inhabitants of Tokyo, indifferent to her suffering. Readers of Colleen Maria Lenihan’s story collection Kōhine will recognise many aspects of Dinah’s life in Tokyo – alienation, lack of intimacy, the haunting presence of a dead family member, a school girl poised to jump from a building, the crows. (Lenihan has an entire story, ‘Directions’, about the crows there). Dinah finds a crow pecking at a rubbish bag outside her building: with ‘every stab, a pool of dark liquid bled from the bag onto the concrete path’. It won’t move out of the way: it ‘just looked at her with its black eyes, looked deep at her as if she were nothing, nothing to budge for’.

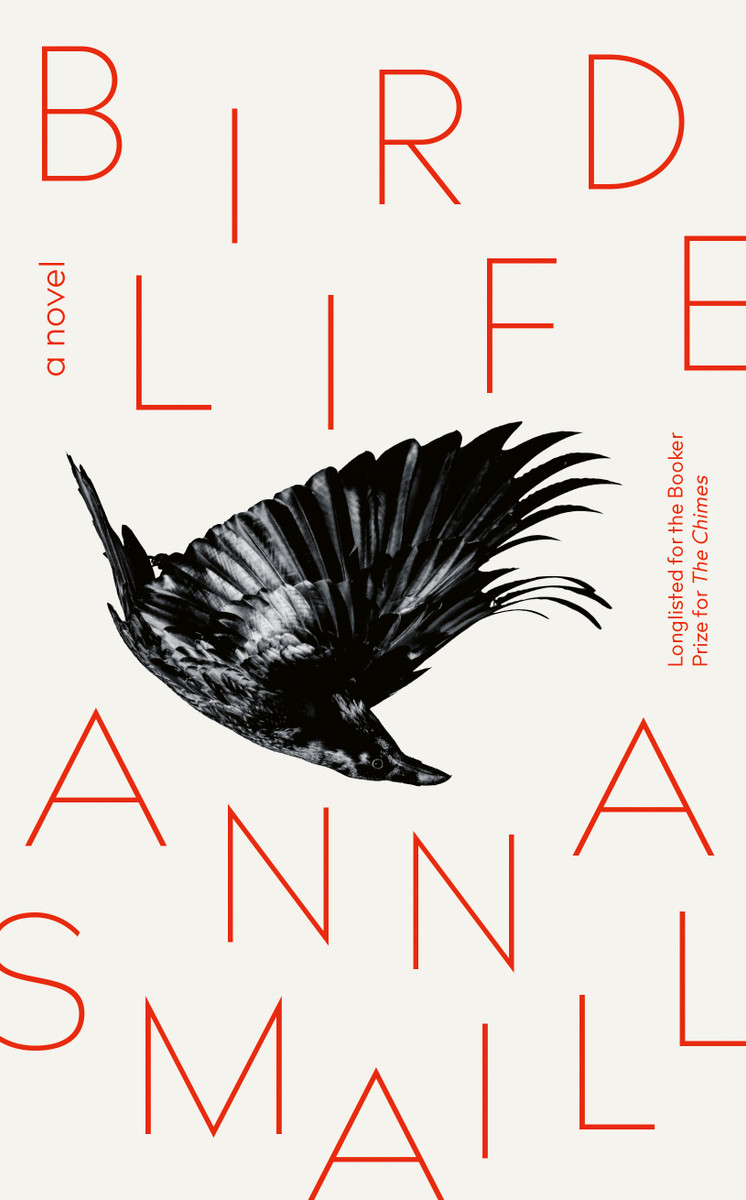

In The Chimes, Smaill’s first novel, a dystopian England is wracked by an unbearable sound. In Bird Life, the unbearable is particular and takes visual form. Dinah is beset by migraines, their ‘dark shape’ suggesting the crows:

Bright spots hung and floated and scattered away when she looked. Soon thereafter the whole world became flimsy like tissue paper … She was blind as she walked, and did not know where she sat, but she sat somewhere in the grass and felt the black wing rise in her head and the true shape of the beast approach.

For Yasuko the birds speak and the world spins and throbs and bristles. ‘The city was speaking to her. A pulse beating beneath the day … It came up through her body and it coursed through her muscles and right to the tips of her fingers’. There are fairytale elements to both women’s stories. Yasuko’s lavish spending on designer clothes and a Cartier watch for Jun depend on a monthly envelope of money left for her at a bank by the father who she believes ‘trapped her’. She shares her past with Dinah in fairytale form: she was a princess with great powers; the king was jealous; she and her young son ‘disguised themselves and disappeared into a neighbouring land’. On the roof of the Seibu deparment store, Yasuko visits a magical shack – a ‘strange encampment’ – to buy birds, fish and beetles for at-home conversations. When Dinah returns to her local park at night, she picks three leaves from ‘the sentry trees. One bronze, one silver, one gold’: this detail suggests the plucking of precious-metal branches in ‘The Twelve Dancing Princesses’.

Like The Chimes, Bird Life is a novel that re-visions the world in a compelling, imaginative and vivid way. Its language can feel over-formal. Readers should not be deterred by the book’s stilted prologue, or think too much about the rules governing Michael’s on-and-off – and very non-ghost-like – presence. This is Tokyo, where an ‘omamori charm’, a protective amulet, dangles from a school girl’s bag. Bird Life asks us to be open to strange things, just as Dinah welcomes Yasuko’s fairytale. ‘Wasn’t it second nature to her, in fact, to follow and to stand looking up at the vaulted space carved out by her brother’s imagination?’ Bird Life asks us to be open to different ways of seeing and hearing, different ways of navigating the world.

This book is available from BookHub and from bookshops around New Zealand.