Patricia Grace’s first book, Waiariki, published in 1975, was a collection of short stories, the first published by a Māori woman writer. Almost fifty years later she is still writing stories. If the pieces in Bird Child are her valediction, they express what Grace holds most dear as a writer: stories of her childhood and youth in a loving Māori and Pākehā family, and the Māori stories, ancient and modern, encompassing the pātaka and the Food Court, the forest and the factory floor, capricious spirits and hypocritical Ministries with their endless reports and ignored recommendations.

The first stories in the book are formed by or in the style of pūrākau, and the act of storytelling itself is visible. In ‘Bird Child’ a baby’s before – and after – life encompasses the songs and stories overheard and absorbed in the womb. The children of ‘Earth and Sky’ are ‘listeners and decoders of secret language’ between their parents. And in ‘all stories so far about Mahuika, Keeper of Fire,’ the narrator of ‘Mahuika et al’ tells us, ‘Tīrairaka doesn’t feature at all. Later in this narrative it will be revealed how this special relationship between the two came to be.’

The superb long title story is influenced, Grace writes in the book’s brief introduction, by ‘waiata tawhito, karakia, oriori [lullabies] and whakapapa.’ Though she encountered these via English translation, Grace was ‘deeply attracted by their emotional and cultural landscapes and the way language is used.’ This story, in particular, demonstrates Grace’s imaginative skill at evoking a ‘long-ago’ world and her ability to write sentences, and imagery, of great beauty. The baby’s mother cries ‘silent rivers in the inert forest light’; the afterbirth ‘slithered, shapeless, rheumy and pulsing,’ into someone’s hands; the sky is ‘curdled with stars’.

In this story Grace imagines both the pre-contact world of warring humans and the vast, busy natural world, with her usual attention to the shape, sound and meanings of words:

Deeper in the forest, the night birds shuffled in the trees. They scratched and scuttled about the strewn floor, squeaked and cried and tapped the earth. Ground parrots loped screeching and growling through the nigh forest. They drummed from hillsides and ridges. Overhead, ruru watched from branches, speaking across valleys and the river, launching themselves, as shadows, to hunt.

The informal tone of the other stories in the pūrākau group suggests they may be intended for a high-school audience. The god of weather, Tāwhiri Mātea, is ‘the boss, TM’. Pūkeko, Mahuika’s familiar, ‘became her security guy, also her spy’. Tīrairaka asks if Māui had ‘to give the Sun the bash?’ In ‘Sun’s Marbles’, Māui is ‘the pioneer of daylight saving’, and humanity enters the world with ‘a great deal of trauma, which included incest, personality change, family break-up and solo parenthood’. This is Grace in educator mode, retelling both the familiar and unfamiliar (Māui was ‘born ugly’, she reminds us) and tempering the ancient with contemporary language and humour.

The second part of Bird Child groups stories about a girl named Mereana, clearly informed by Grace’s own youth – episodic, atmospheric slivers that evoke a wartime Wellington familiar to us from her novel Tū and her 2021 memoir From the Centre. This is a place where wind ‘carried armfuls of litter which it had gathered in the funnels of streets’ and Mereana watches her father, ‘with a shade on his torch and his lunch in a tin bag, going to his job at the Freezing Works’. American soldiers dispense chewing gum on the train; buses smell of ‘sweat and smoke, Brylcream, apples and vegetables; cousins go eeling or eat golden syrup on hot frybread; at a dance a boy stuffs ‘his face full of cheerios with tomato sauce’; and soldiers ‘come back home singing in another language’.

The nostalgia of some of these stories may make them seem soft-centred. Darkness seeps into the bright order of family life. Racist neighbourhood girls slice her with a piece of glass and their mother calls Mereana and her brother ‘dirty’. Mereana’s father enlists with the Māori Battalion and is away fighting so long she struggles to remember his face. But darkness doesn’t linger: on her father’s return Mereana is relieved that she does recognise him, ‘his scratchy chin, the wormy veins criss-crossing’ the backs of his hands. For Mereana, songs like ‘Blue Smoke’ and ‘Red Sail in the Sunsets’ ‘made it seem as if the whole world was colouful, floating and drifting’.

The stories of the third section of the book are largely written since Grace’s last collection, Small Holes in the Silence (2006), and include a re-working of a 1972 story, ‘The Machine’. The deft and moving ‘Matariki All-Stars’ – which first appeared in the anthology Black Marks on the White Page, edited by Witi Ihimaera and Tina Makereti – is a stand-out example of Grace’s gift, evoking the complexity of family relationships and emotions in compressed short-story time. Watson, a widower, struggles to raise his girls and his overbearing older sister, Zelda, a surrogate mother to him when they were growing up, absconds with the baby. Watson and daughter Lainey drive to Zelda’s farm to snatch back baby Dixie. The girls, he tells Zelda, are ‘crying every day’.

‘Because they miss their mother, you fool …’

He opened the van door and strapped Dixie into her cocoon on the middle seat, words slicing him from behind.

‘… who shouldn’t have smoked in the first place. Her choice not to have chemo.’

‘Shut your ugly mouth,’ Lainey shouted from the window.

‘Don’t talk like that to your aunty,’ Watson said …

Grace’s body of work is one of political activism as well as polished sentences, profound empathy and character-rich communities. The despoiling of the natural world, fueled by human arrogance and ignorance, is a recurring thread in Grace’s work, and in Bird Child it’s woven into both the mythic and contemporary. To share stories, and to return to them to seek out new possibilities of meaning, remain vital acts in Grace’s work. ‘The Unremembered’, for example, is a Rona-in-the-moon story, a pūrākau explored Grace almost twenty years ago in ‘Moon Story’’ as well as in her first novel, Mutuwhenua (1978).

Here Rona is warned of the perils of unremembering ‘about interdependence, unremembering about the mauri of all things, unremembering that all have an important place in the universe.’ People, who are the ‘last-to-become’ in this world, no longer know their own place in the order of things. Earth sends out warnings (‘Fire, Water, the Plague’) but too many people are either ‘bystanders’ or ‘deniers’. ‘Listen to the birds,’ the collection’s final story warns. Are the lockdowns of Covid ‘a wake-up call? Papatūānuku fighting back?’

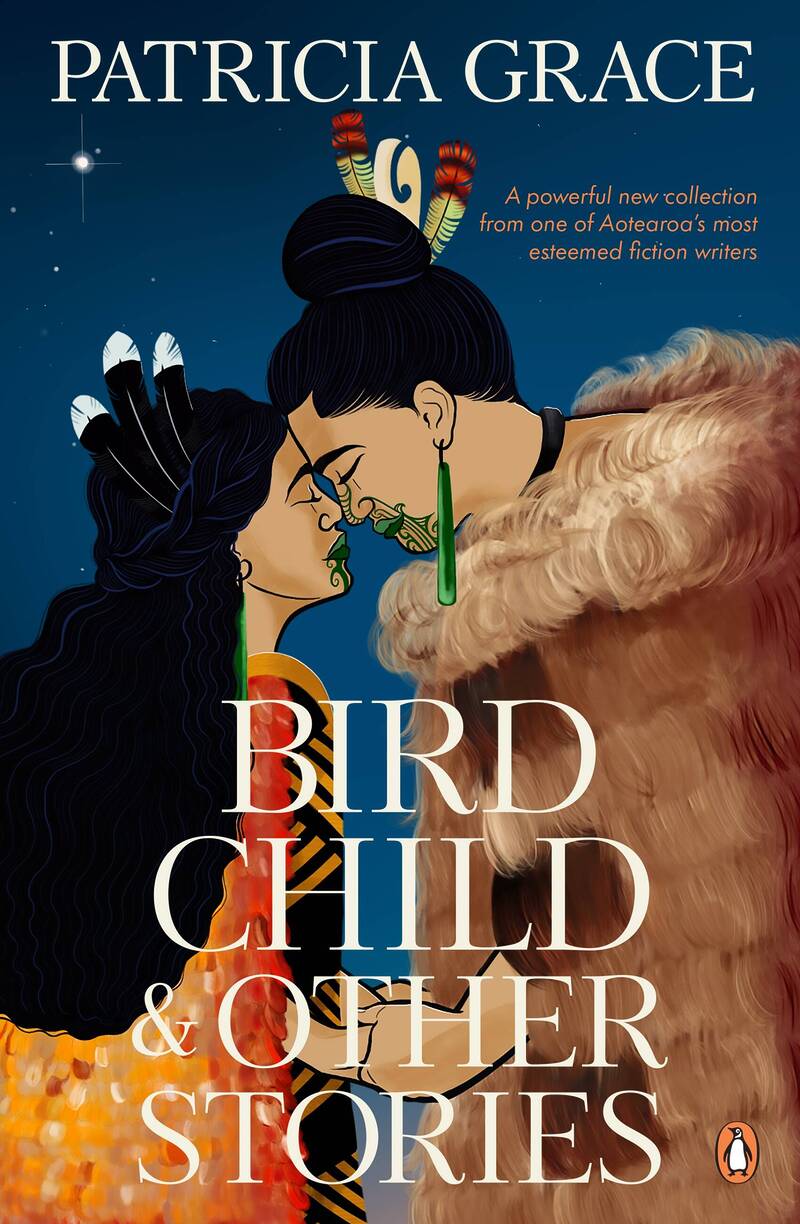

Perhaps this is also Grace in reflective mode: she turns 87 this year, and the book is dedicated not only to her late husband, Kerehi Waiariki Grace, but to their ‘children, grandchildren, great grandchildren and great great granddaughter’. (The cover art is by her granddaughter Miriama Grace-Smith.) The list of her bibliography and awards at the end of the book stretches over four pages. Bird Child is not simply a collection of stories: it is a reminder of Grace’s legacy and her gift.