In a 2016 kōrero between the Polish poet Adam Wiedemann and New Zealand writer Vivienne Plumb, Wiedemann talked about reading a poetry anthology from New Zealand. ‘I noticed that the most popular topic in your poetry is a stone,’ he said. He and Plumb both had experience judging poetry contests, and she recalled him saying that ‘topics in a Polish poetry competition would include death, death of a close family member, death of a good friend, the death of a pet dog, the death of nature, and the death of the world’. New Zealand poetry competition topics, Plumb joked, ‘would include nature, a close family member in nature, a friend doing something out in nature, a dog or another animal in nature, the environment, nature worldwide, and a death in nature’.

Tusiata Avia’s 2004 debut was called Wild Dogs Under My Skirt, but nothing about her work has ever evoked the banal pastoral. Dogs – real and metaphorical – are feral and dangerous.

I want my legs as sharp as dogs’ teeth

wild dogs

wild Samoan dogs

the mangy kind that bite strangers.

In Avia’s poetry, stones are not positioned in sweeping New Zealand landscapes, but in Christchurch where ‘Queen Victoria – made of stone – […] stares into the air past every kind of massacre’ (‘Massacre’, 2019), or in a Samoan village (‘My Dog’, 2014) where, in a kind of colonial parable, a dog is exiled from its house by a Palagi interloper:

Bingo he sleep outside and eat da stone.

Only feed Bingo da stone everytime.

We call

BingoBingoBingo

and throw da stone to him

and laugh

HaHaHa

and da Palagi man shout to us

You kids stop throwing stones at the dog!

Avia is a bold, uncompromising artist with a sharp intelligence and caustic wit: her poetry swaggers and her poetry sears. In the last two years too many stones have been flung her way and now she is the dangerous one: ‘I am the girl who writes like this / I am the girl who bites like this’ (‘Glorious ways rap’). The burden of those stones, physical and psychic, is the heavy heart of her superb new collection. Among the things she carries: the Christchurch Mosque killings (‘I went to Al Noor to remember. / To say sorry with lilies, the flowers for death, / white for peace, / pink for the hearts stopped beating’); the Christchurch earthquakes (‘The quake families sit in rows and rows and rows. / […] We sit under the sky, no walls, / no roofs, we will be safe here’); an accident that broke both feet and hospitalised her for months (‘tripping the jagged jaws of a gin trap’); and the hysteria after Stuff published a video of Avia reading her poem ‘250th anniversary of James Cook’s arrival’ in New Zealand’. The poem was from The Savage Coloniser Book, published in 2020 and poetry winner at the 2021 Ockham New Zealand Book Awards. In February 2023 the stage adaptation was about to launch at the Auckland International Festival of the Arts, the beginning of a national tour.

In the poem ‘Big Fat Brown Bitch 56: She is sick of writing poems no one ever reads’, in the book’s third section, Avia laments:

I’m sick of writing poems no one ever reads

except for middle-aged white people of a certain demographic

and smiling white-haired ladies in a line at a book signing table

and classrooms full of brown girls who are in awe of me.[…]

There are countries where poets are performing to football stadiums

and the roar of prisons. Poets are being arrested and tortured

not by their own boredom but for conspiring against the government

with poems.

Writers should be careful what we wish for. When Stuff published the video as well as an abridged version of the Cook poem, the petty fury of social media whipped itself into a malicious whirlwind of vitriolic abuse, including racist slurs like ‘overstayer’. The usual suspects – in politics and broadcasting – piled on and eleven complaints were made to the Media Council, with Stuff accused of inciting ‘racial hatred’ and the poem described as ‘borderline terrorism’.

None of the complaints were upheld. But the personal attacks on Avia, including hate mail and death threats, continued. This is the backdrop to the writing of Big Fat Brown Bitch – Avia in hospital for months on what she calls ‘a weird, enforced writer’s residency’, while her poetry made headlines. ‘Really, bitches?’ she writes in ‘Diary of a death threat, 1 May 2023’. ‘I write a poem about Captain Cook / and you scurry around in your dark spiderweb, / in your pyjamas?’

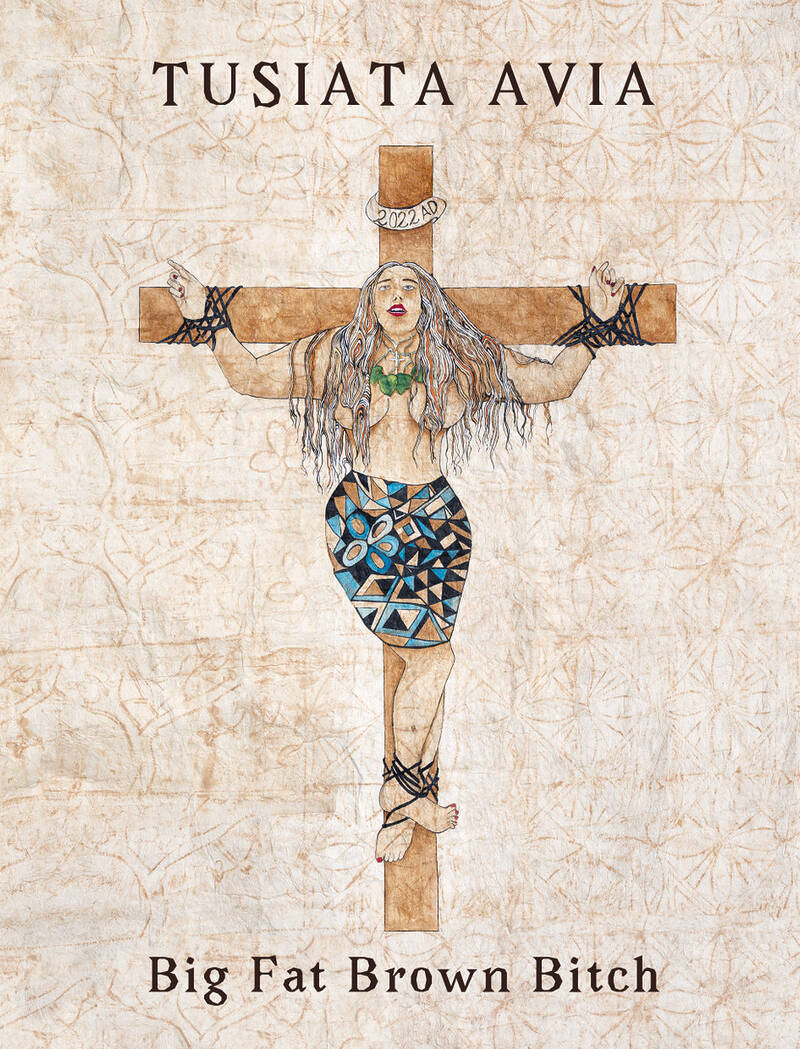

Where another writer might crumble, Avia remains alert and undefeated. She listens for the Samoan goddess of war who ‘simmers, / waiting for my call’ to burst from the underground, clubs spinning. This book is the result. Everything about it is audacious: the title; the tapa cover art by Emma Tui Gillies of a Pacific woman bound to a cross; the mocking epigraph No white people were harmed in the making of this book; poem titles like ‘Why don’t I have a big Tongan husband or Dwayne Johnson to help me?’

The humour is audacious not because the poet-as-wit is unusual, but because there’s no simpering, posturing or ironic malaise here. Under actual attack, Avia attacks back. ‘Werewolf’, the first of the book’s four sections, directly addresses the ‘Cook’ crisis, beginning with a Newshub article on ACT’s attack and offering the offending poem in blackout mode. Avia names and shames in poems like ‘Hey David’ (‘Poems are awesome, bae, you don’t need to freak out’), ‘Ode: Don’t punish the wealthy’ (‘Oh, Nicola, I really don’t have time for this today’) and ‘Glorious ways rap’:

Winston, who you callin’

a ‘mediocre poet’? Bro, you so irrelevant

and Aotearoa, we all know it

David Seymour, who you callin’ racist?

you just some double-talking, weaponizing, headline-grabber, face it!

She mocks ACT’s commitment to ‘Free Speech’ – ‘except when it is a poem / twisted into a headline / in an election year’ – and applies her ruthless wit to the Stuff complainers. This is from ‘New Zealand Media Council Complaints Case 3392’:

My daughter locks me in the bathroom and says through the door:

‘Mum, stop that racist violence dressed up as art, because, Mum,

poor white people disaffected by the effects of globalism couldn’t

say those things.My daughter slumps down outside the bathroom door in tears and

whispers: ‘I’m tired of my acceptable ethnicity. We brown people

have all the privileges now. We can say anything we like and get

away with it.’[…]

As I bound away, my daughter screams into the street behind me,

‘Mum! I don’t care how hard your upbringing was in Christchurch,

it’s just not fair that you get freedom of expression. I’m sick to death

of us brown-skinned female poets and the generations of privilege

we come from.’Now the neighbours are out on the street, wringing their hands and

shouting, ‘Our children have access to this poem!’

In the collection’s triumphant final section ‘Malu / Protection’, Avia includes ‘the dark versus the light’, her response to a Pākehā poet who criticised her work on Radio New Zealand:

Why so dark, Brown Girl, why so dark?

[…]

Cheer up, Brown Girl

Sit in a room and blast Mein Kampf at yourself

and stop moaning and bitching and complaining

about racism and colonisation and white privilege

People get sick of that

It might be in fashion right now

but it won’t last forever.

Why should Avia ‘cheer up’? She’s grown up in a country reliant on glib tropes around Pacific people, tropes that diminish and belittle. At the hospital a nurse lectures her:

blah blah blah Body Mass Index

blah blah blah Do you know about food?

blah blah blah You big fat brown bitch.

The swirling societal disapproval is internalised. At school: ‘I was grateful that my name was Donna / every time I heard another brown kid’s name’. At home: ‘When she puts something in the microwave / she is a big fat stinking bad mother lazy pig’. In a bookshop: ‘when I know I’m being followed / (because what is she doing here?)’. When she loses weight: ‘me looking at myself in the whites / of the eyes of people who smile at me now’.

Avia’s impatience with the public theatrics of politicians extends beyond the Stuff furore. Jacinda Ardern appears in ‘Memorial 2021’ (where she ‘walks the aisle like a bride in black’) and in ‘Dawn Raids Apology 2022’ (where the ‘ie toga is spread over her head like a bridal veil’ for a truncated gesture towards prostration: ‘she has demanded not more than a minute’). Offer Christopher Luxon, she suggests, ‘a hi-vis vest so he can hammer in a few nails with your / two brown brothers smiling in the background’. This is the beginning of ‘Big Fat Brown Bitch 23: She receives an election-year visit’:

If you are sitting in a garage in South Auckland with your two

brothers, tell your sisters to stand outside on the street, flag down

flash cars and check for gang members or members of parliament.If you are sitting in a garage in South Auckland with your two

brothers, hide your BA, MA, PhD and your MNZM for services

to the arts, the sciences, sports, healthcare and technology. Think

instead how you might get into a gang and a life of crime.

The final section of the book returns to a subject Avia has addressed before, the rituals and meaning of tatau (tattoo), and the vā that the children of the Pacific diaspora must navigate. Here the poems play with visuals and movement on the page, with the sounds and sensations of the act. Avia remains unsentimental: there is physical pain here, and the pain of loss – of people, language, knowledge:

How do we trace the whakapapa of our symbols < > when our

grandmother is dead < > and our father is dead < > and our great

uncles and aunties are dead < >(‘The whakapapa of a symbol’)

In the ‘Malu: She has her legs tattooed’ cycle of poems there is also shame, to be one of the ‘light brown / daughters whose ears don’t / understand the lāuga, / the oratory’. Again, disapproval is internalised: ‘The stupid half-caste can’t speak Samoan bloody New Zealand-born why / don’t you go back to your own country.’

But this book, emerging from places, memories and experiences of anguish, feels more triumphant than melancholy. ‘The waves of shame break / to cleanse you / to cleanse you’, as the last lines of the final poem tell us. Avia’s skinny self is ‘broken’, but when she gains weight she is a ‘triumverate’ with a body ‘big enough for three women to share’. The collection’s title is not a slur but a sign of her power, now and through the ages:

A birthing woman is a goddess

I have the body of a birthing woman

One that constantly splits open to birth another bitch

What else splits open to reveal a whole new squalling universe?Admire my big fat brown body, bitches!

Admire it!