Deborah Robertson’s YA novel Before George is big – a hefty 400+ pages long – and an impressive debut. Set in the 1950s, it centres around a 13-year-old’s search for identity. When she boards a ship in Cape Town with her mother and younger sister, Marnya Scheppers suspects that her volatile father is unaware they’re leaving South Africa. Her mother tells the girls that they’re just going on a visit to their uncle in New Zealand. What Marnya doesn’t realise is that they’re running away from home – and that she, for the first weeks in the new country, has to pretend to be a boy named George.

Robertson captures Marnya’s voice with ease, from the very first page; Marnya’s touch of stubbornness, sense of self, and great need to understand and interrogate her surroundings hold truth. When her mother says, ‘you just have to trust me,’ with eyes ‘hard as baubles,’ Marnya can’t accept it. ‘I knew only that I didn’t want [to be George]. Didn’t want his legs, his short hair, his khaki shorts. I wanted me.’

Marnya’s identity is transformed by tragedy: the train they are travelling on plunges into a gorge. The infamous 1953 Tangiwai disaster has horrifying consequences for Marnya; she’s now alone, in a remote area of a country she doesn’t know, with no idea of her uncle’s true name or location, attending a high school in Ohakune where they speak only English, her second language. ‘I didn’t know who I was,’ she thinks, but knows it ‘was not safe to be a girl here. Not without my mother.’

Paranoid, traumatised and alone, Marnya clings to her mother’s edict that ‘there is nothing more dangerous in a world than being a girl’. She insists to everyone that she is George, claiming no knowledge of her previous life or name. This is a defence mechanism. The details of the abuse her mother was trying to escape, alongside the trauma of the disaster she survived, are woven into the book, in flashback, even George’s dreams revealing her fears and fraught memories. It isn’t until she’s been at her new school for some time, living on-site with the crabby and difficult Mrs Taylor, that Marnya grasps that she has more control over her identity than she realised. She shows her new friend, Will, a welt on her ankle, ‘a relic from my father’s belt’, and tells him it was a snake bite.

You’re good at writing stories. My teacher had told me that once, I remembered, and a surge of relief rushed through me. It was all a story. The story of George Shepherd. It was something I could make up. Who’s to say George Shepherd had never seen a lion in the wild? That he wasn’t scared of snakes?

George Shepherd could be anybody in the world.

Robertson doesn’t minimise the deep psychological effects of George’s trauma, but presents them in a way that is both truthful and indicative of a young teenager struggling to find her own place, learning to manage a strange new world. Slowly recovering her mojo, George encounters a myriad of foreign concepts, including cold weather, the classic schoolyard game of bullrush, and wearing sandals without fear of snake attack.

I learned to play the games of the boys. The rules were simple: if you were angry, you hit someone; if you were tired, you stopped playing; if you were upset, you kicked a tree or whacked something with a stick. Anger was explosive but brief, forgotten by the time the lunch hour had passed. Injuries were something to be paraded. Bravery, particularly foolish bravery, was for some reason a sign of great intelligence.

George is the only girl in her form, albeit incognito, and she begins to form friendships with a number of the boys – especially Percy, a child with muscular dystrophy who is often alone. In the persona of George she finds sanctuary from the threats of the past. There are no issues of gender confusion here; George has no existential doubt that she is, at heart, a girl. When she makes a friend promise ‘to pretend that I’m a boy’, he’s confused, and she can only think, not say, the reasons:

Because if I was a boy I was safe. Because if I was a boy no one would beat me. Because if I was a boy then I would be the same as everyone else.

Most of the main characters in the story have plenty to offer George in her grapple for understanding and truth. Percy has much to teach George about suffering and life as he battles the slow loss of his strength. George often feels ‘angry at myself, for not fitting in, or at my mother for bringing me here’. She asks Percy why he’s ‘not mad at God’ for ‘you… well, for being in a wheelchair?’ Percy replies: ‘What’s the point? … I don’t much like being angry, do you?’ Mr Cletis, the English teacher, hovers in the background, a touchstone or mostly benign mentor, offering flashes of support through a slow reveal of his life: ‘I know what it’s like,’ he tells her, ‘to lose your family. To be an orphan, as such.’

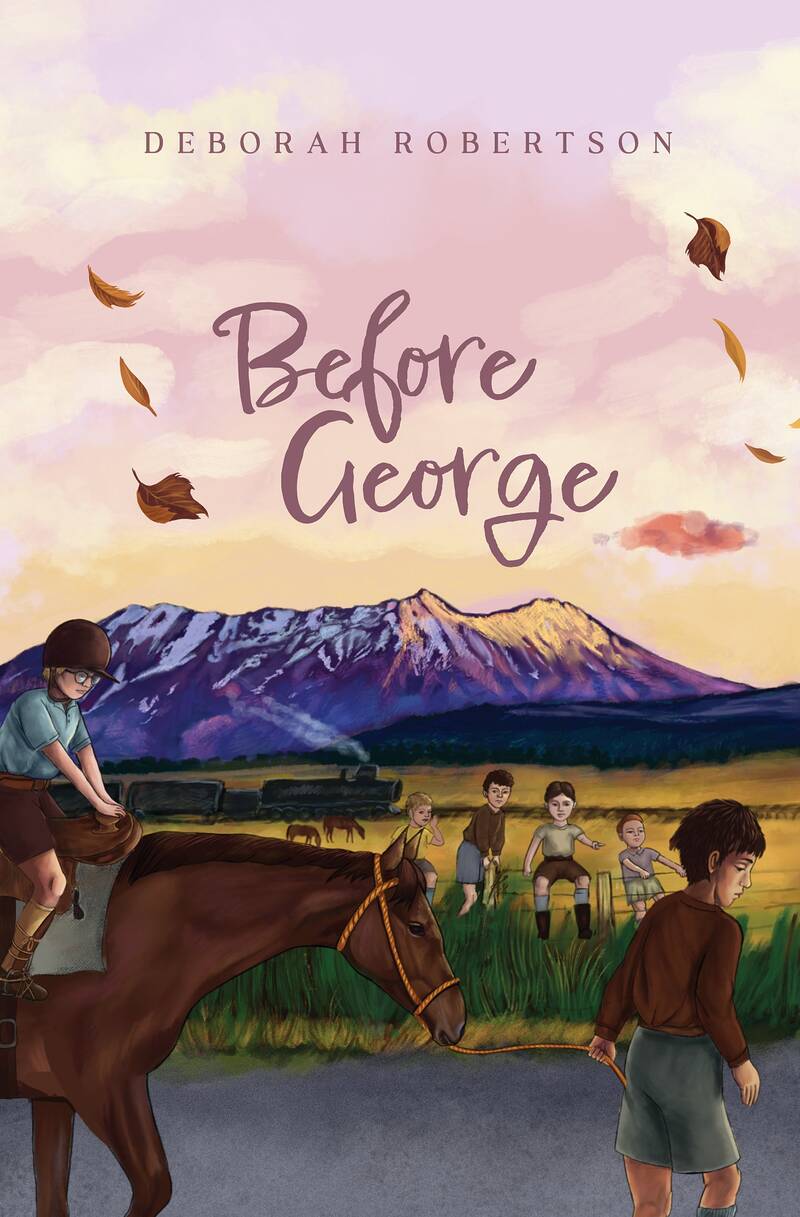

The many horse-loving young readers who have read through Stacy Gregg’s MG horse-and-pony club novels will be delighted by George’s skill with horses. One hopes they will pick Before George up; while the novel does have horses on the cover, the pastoral scene depicted is soft and romantic, and doesn’t necessarily reflect the raw story inside. This may not draw the readers of the intended age group. Still, tweens who are strong readers and young teenagers will revel in George’s wins and losses, and the adventures that shape the novel. It doesn’t fall into the trap of relying on historical events and attitudes to carry the story; George’s emotional journey and the travails she faces are as real as the depictions of the Tangiwai disaster, and at least as well-drawn.

Impersonating a boy in an era where girls have less freedom can be a device for an author, to allow a young woman to press past the boundaries that should constrain her in the time period. Tessa Duder’s The Sparrow, published earlier this year, makes use of the same device enabling a character to escape a terrible situation. Similarly, Marnya’s identity as George is initially to escape a difficult place, but ultimately is so tightly wound into her journey, her history and her preoccupations that it is essential to the novel.

Robertson’s writing is deft and thoughtful, and the character she’s created in George has real heart, of the kind that keeps readers enthralled until the very last page. I can’t wait to see what Robertson does next. By the end of this novel, George’s journey teaches her what we all need to learn, that ‘nobody chooses their name,’ and the only choice we have is ‘what to do with it’.

One Comment