Part One of Emma Ling Sidnam’s debut novel – its manuscript the winner of the 2022 Michael Gifkins Prize – opens with the query ‘So, where are you from, then?’. This is a thoughtless question from an English tourist at Auckland Art Gallery, where Sidnam’s protagonist and narrator Laura is working. Laura’s initial response is simple: ’Here.’

On the surface, it’s an act of defiance – an attempt to shut down the tired line of questioning with which people of colour in white-dominant societies are all too familiar, a desire to be seen as more than race, and to assert one’s place in their home country. However, as we learn more about the narrator, it’s evident this oblique answer is also a defence mechanism, because Laura really doesn’t know where she’s from; she’s a fourth-generation New Zealander and ethnically Chinese on both parents’ sides but can’t speak the language and never calls herself Chinese.

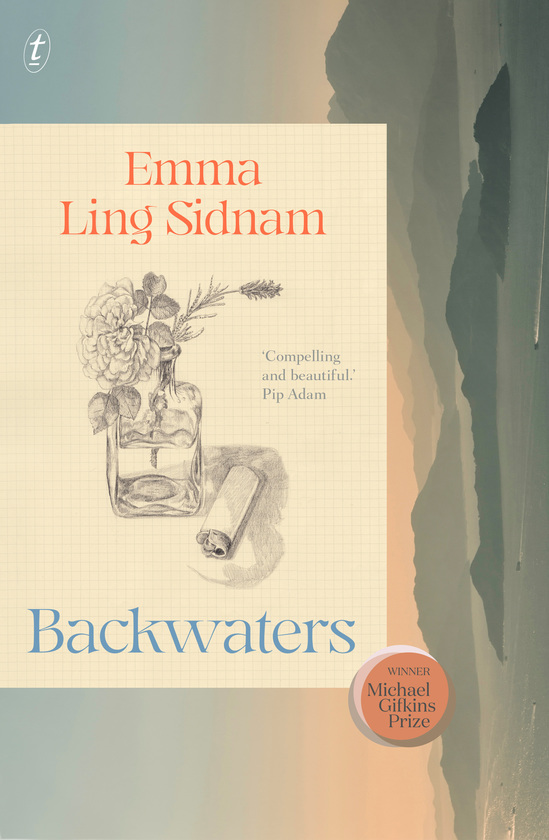

This is also the question Laura sets out to answer over the course of the novel, propelled by her supervisor’s request for her to write ‘Chinese New Zealand stories’ as part of a project commissioned by one of the gallery’s artists. Laura resolves to write about her maternal great-great Grandfather Kaineng ‘Ken’, one of the earliest Chinese settlers in Aotearoa who worked as a market gardener during the gold rush. The writings form ‘Backwaters’, a metafictional recounting of Ken’s life, which is woven throughout the frame story. These chapters in particular highlight the lyricism of Sidnam’s prose. Ken’s journey reads like an impressionist painting – informed by yearning and a romanticism for the everyday. He’s quiet and introverted but pays careful attention to the world around him. His family’s callousness is at the root of his loneliness, but he finds a new ease among the few companions he keeps.

Laura too is naturally reserved but, unlike Ken, she relies on her family as a grounding force. In Gilmore Girls fashion, they meet for regular weekend dinners, and while there’s obvious distance between members of the clan, these are the people who give her a sense of belonging. Together the two narrative threads draw touching parallels, reflecting and refracting through history vivid experiences of adolescence, love, and grief.

The decision to fictionalise Ken’s story is compelling. On one hand, it’s an effort to maintain a veil between real and not real. Laura is shy about her work, and from the outset suggests her contribution should be accurate to be truthful, free from her own biased notions about what it means to be ‘Chinese’. However, turning reality into invention also gives an additional layer of richness to the story. She adapts life into art, but also pays tribute to the way life itself is an art. Laura breathes life into Ken, and the blurring of fact and fiction gives rise to a narrative beauty she can claim as her own.

As Laura writes Ken’s story, her life blooms and expands. She begins to participate more actively in the world around her – growing closer to her family, striking up a relationship with a charming (although sometimes naïve) colleague, and joining a local young Asian artist collective. However, the newfound connections are quickly dampened when her mother uncovers a family secret – that she was adopted as a ‘found’ baby from an orphanage in Hong Kong. Because of this, Laura’s authority to write Ken’s story challenged:

Can I even use his story if he’s not my blood relative? Does adoption mean I get to claim that whole line of heritage?

Family is a touchstone in Laura’s life, and to have an already-tenuous origin story redacted throws the dynamic of her loved ones into a state of limbo. After the family cuts Laura’s beloved Grandpa off for withholding this information, it’s her mother who shows remarkable grace in pushing Laura to reach out to Grandpa when she needs help translating Ken’s journal for her writing. The small gesture reveals her courage and determination not to let generational trauma burden her own children. Laura’s mother is the family’s backbone. She makes the ultimate sacrifice in forgoing her own complicated feelings about her father to allow Laura and her sister Max an opportunity to connect with their grandfather in a way she never could.

It’s been a week since Mum said I could talk to him, but I still haven’t reached out to him. It’s just felt too big in my head.

‘Go whenever you want,’ Mum affirms.

She looks at me and it’s like I can see through her. She wavers, fragile but certain. Love surges through me, sudden and strong, and I hug her.

The relationship between Laura and Grandpa too is a tender development. Out of the adoption revelation, several other secrets are revealed – Laura’s grandparents did not marry for love and were neglectful parents to her mother. These smaller epiphanies force Laura to face something we all reckon with as we get older; parents are not perfect, and they were people before us, with lives outside of us.

Through translating Ken’s journal, Grandpa offers Laura a piece of her culture she cannot access, a language exchange that in turn gives way to Laura’s forgiveness. Both parties are generous in their offerings, and uncynical in their trust, affording Grandpa a second chance at redemption. His conviction that the two share history despite not being blood relatives reassures Laura’s about her authorship and identity.

‘All you can do is your best, Lorry. You’re doing your research and nobody can ask more than that. And this is our history. It’s not like you’re appropriating anything.’

It’s Grandpa’s real history and my non-biological history. But I’m grateful to Grandpa for calling it our history. Like I really can claim this too.

When the shock of their new reality dies down, Laura seeks answers to her heritage with renewed energy: ordering a DNA test from the internet, researching orphanages, and planning a solo trip to Hong Kong. While she longs for a definitive answer, part of her also hopes she’s not ‘100% Chinese’, confronting a self-identified internalised racism. The need for tangible truths verges on obsessive and puts a strain on her relationships. When the unknowability consumes her, she worries about being too self-involved. Beneath her concerns about ethnicity, Laura is navigating same social pressures as any young woman – self-image, unexplored sexuality, imposter syndrome.

In Backwaters, potential leads often go nowhere, or to a place the protagonist doesn’t expect. Laura’s arc then is a story of becoming – in the absence of a biological certainty, she discovers power in deciding who she is, and this is real freedom – to honour the past and not let it be a prison. Laura is ‘no longer desperate for answers about our heritage and identity’, realising ‘it’s not as important as family and who we choose to be.’

Sidnam’s pen is delicate and precise, but rarely overdetermined. She shows us that even if Laura is unsure of her cultural identity, she’s still capable of experiencing the full range of human emotion – she’s both growing up and fully-formed. She may not know where she’s from, but she finds out who she is. Laura is here, and that is enough.