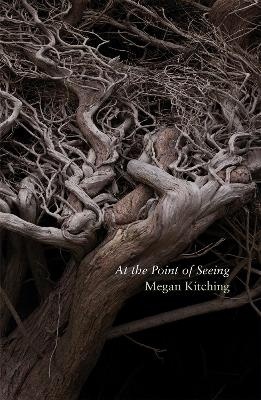

In her tenderly written, quietly powerful debut collection, At the Point of Seeing, Megan Kitching highlights the complex inter-relationships between the environment and people, and between people and people.

At the Point of Seeing opens with ‘Blue-tide’, and its first lines, ‘With half an eyelid / I step over the eggshell night / unwoken’ convey an image of a sleepwalker. The poem comprises only six lines, yet, in the context of the book, its magnitude becomes clear. The ‘I’ persona is all of us, barely awake to the fragility of the earth under our feet and our existence in the universe.

‘Eye Contact’, with its image of a photographer focusing on a sea-lion, reinforces this sense of detachment from nature, of viewing it at one remove. There’s a meta aspect, with Kitching making the reader complicit with the photographer: ‘Whakahao rears to a cliff: / black ledge of sea-breasting chest, / disdainful nose. The photographer’s /doubled eye blinks black’. And a reader can’t help but blink, too.

Kitching has a PhD in English Literature from Queen Mary University, London, on British natural-philosophical poems of the 18th century, and this botanical appreciation is evident throughout. Fauna and flora adapt amid the encroachment of ‘walkers’ – two-legged humans.

There are references to white settler-introduced fauna and flora such as thistle and swans, co-existing or competing with indigenous species which the poet names in te reo, such as in ‘Riroriro’. Naming is important in terms of relationships of power, and Kitching highlights the tension in this in ‘Botanising’. A young woman sits on a verge and tugs a plantain leaf, ponders a buttercup, when ‘a man / leaned out to ask me what I was doing./ With no thought, I said I am waiting to be picked up. / If you stay there, you will be, he said.’ And in a sequence titled ‘Weeds’, what may be weeds to one culture, is food to another, a tension highlighted in a poem naming a species in both in te reo and Latin: ‘1. Pūhā (Sonchus kirkii)’; there’s another with three names, English, te reo and Latin: ‘v. Rimurapa / Bull Kelp (Durvillaea antarctica)’.

This mix of the introduced and the indigenous is Kitching’s understated way of referencing Pākehā colonisation of Māori such as in ‘On Kamau Taurua’: ‘ …extinguished voices / in the harakeke rustling with the sound / of nothing now but thistle and grass’. Implicit is: Whose land is occupied by the thistles, described in another poem as ‘heraldic’? Who and what are they displacing?

Offering a further social commentary on issues of intrusion and colonisation is the remarkable poem, ‘Penguin Colony, est. 1992’. The setting is a ‘blasted amphitheatre, disused quarry’, of ‘ringed stone, post holes, littered bone’ from which penguins emerge. In fact, there is a real-life Oamaru Blue Penguin Colony, a fenced-off stadium where people pay to watch penguins arrive each evening. Its logo proclaims ‘Est 1992’, but Kitching’s poem shows the idea of a penguin colony being established in a particular year is a man-made construct. The birds have been coming ashore there for aeons, but now they are located within a globalised capitalism model. The walled-off set-up ensures tourists can’t see the creatures for free in nature.

This raises a question: what is a ‘colony’? Today, both penguin and human colonies have geopolitical aspects. Aotearoa was once a ‘colony’ controlled by Britain, with issues of dominance, and loss of land and identity. The penguins, meanwhile, are a ‘colony’ of a commercial enterprise. Humans have colonised their space.

However, Kitching contextualises this within the Covid lockdown, and subverts it:

‘ … the centre locked / against plague, residents burrowed / under the cape’. Firstly, there’s idea of people hiding under a flimsy cape, echoing humans’ (sweet) mammalian origins after the asteroid took out the dinosaurs; and secondly, geological solidity – the Oamaru centre sits underneath Cape Wanbrow. Kitching goes on to conjure an image of unfazed penguins finding their way through the absurd vacant grandstand to the sea – like something from TV’s Life after People.

Indeed, one way of interpreting the collection’s ambiguous title is: Are we ‘at the point of seeing’ what is happening to our planet? In this, Kitching continues an inquiry raised in the compelling climate-change anthology No Place to Stand. Its introduction says, ‘Poetry has a long history of trying to answer the unanswerable … and questions don’t get much bigger than: how do we cope when we are caught up in an existential crisis on a planetary scale? A crisis that we have caused?’

Kitching’s approach is to distance the authorial self (with the exception of ‘The Horses’, which, while brilliant, has a shock and urgency that strike a discordant note). This allows a reader ways into difficult subject matter like colonisation, climate emergency, and the end of the world. It’s achieved through contrast, wordplay, rhythm, and variations in form.

‘Herb Robert sonnet’, is in free verse with a traditional rhyming couplet at the end; there’s the anaphora of ‘v. Rimurapa / Bull kelp’ with its repetition of ‘what’ earworming into an incantation to a ‘you’ persona; sonic playfulness in ‘Crematorium’, ‘What a word …. / the rounded O to the I, /come to rest at the end, the em, the um.’; the thin, jagged column of ‘A Bee Against a Window’, reminiscent of Eileen Myles; the found poetry premise of ‘Growing Advice’; and a palindrome effect in ‘Sunstrike’ in which a prosaic drive in a car becomes an Icarus moment.

Such variance could be unsettling, but here it is a visceral way of experiencing the eco message: the reader either adapts to changing forms or closes the book. Sure, that’s an analogy for humans and climate change, but Kitching turns the lens on our changing selves, too. In ‘Walking is Controlled Falling’, there is a poignant personal reference to the ‘I’ persona’s mother, ‘who was / beside me in that momentary black / and now is gone’. This is a gift of profound vulnerability in which Kitching offers no neat resolution to anything, with the poem concluding, ‘I wrap myself and go on, walking and falling. / I may never get used to this’.